Sabaya Makhadet El-Kohl (The Young Girls of the Kohl Pillow), a play that explores the lives and constraints of women in southern Egypt, is playing in Cairo until Monday.

At the small El-Talia theatre in Cairo, folk motifs are displayed on the wall. A woman with Nubian features is sitting on a black chair. In front of her, a traditional bottle of kohl is placed on a cushion. The woman remains frozen for a moment. Then, once the audience is seated in the room, she gets up, takes the cushion and heads for another, older woman, to whom she gives kohl. She looks around, then looks at her sewing machine. Then begins to speak: “The little girl becomes a young woman …” This is how the story begins.

With The Young Girls of the Kohl Pillow, well-known director Intessar Abdel-Fattah has resumed his play Makhadet El-Kohl (The Kohl Pillow), which shed light on the world of women in the south of Egypt.

The Kohl Pillow was one of the earliest and most successful plays by Abdel-Fattah when it was staged in the late 1990s, winning him the best play award at the Cairo International Festival of Experimental Theatre in 1998, and going on to complete extensive tours around the world.

The sequel, Sabaya Makhadet El-Kohl (The Young Girls of the Kohl Pillow), draws more on Egyptian heritage while exploring the concept of polyphonic theatre. The play is currently being staged at El-Taliaa theatre, and closes on Monday 17 February.

In it, Abdel-Fattah takes over and develops further the previous performance, taking us to a Nubian oasis culture, to a place where women hide their beauty products, including kohl, a rich, dark powder used as eye makeup since the Pharaonic era.

Abdel-Fattah uses kohl to immerse us in the world of women in the south. The play breaks with the traditional dramatic structure. The dialogue, written by the poet Kawthar Moustafa, is limited to a few sentences inspired by proverbs and sayings from rural society. Little by little, we are unveiling the suffering and repression of women, imposed by habits and customs.

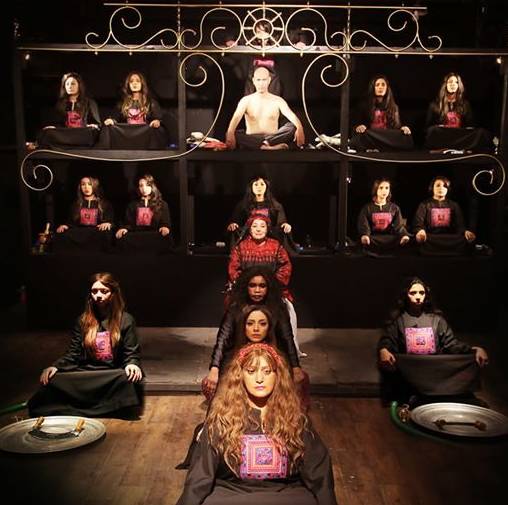

Abdel-Fattah is inspired by polyphonic theatre, based on the decomposition of an idea into several levels and aspects, all brought together in the same scene. The stage space is divided into two planes: a large bed at the back of the theatre, then copper bars in the form of six cells, where women are imprisoned.

The front of the stage is primarily reserved for the main characters: the grandmother with her sewing machine, a dancer whose movements express the idea of freedom, the young woman with Nubian features who has something mythical, and another covered with a scarf, alluding to the oppression she has suffered. The only man in the show is a dancer, often seated on the floor or lying down doing nothing. His movements are reduced to what is strictly necessary.

Cultural heritage

The songs, the music, the rhythms play an essential dramatic role and give rise to an elaborate choreographic expression.

As such, Abdel-Fattah uses folklore songs from the oases of Sahara and Nubia, with rural children’s songs evoking superstitions. Rhythms are often created by household tools and folk instruments. Young girls play with wooden clogs on which portraits of village women are painted. Several actresses use choppers, generating an overwhelming rhythm which reflects the crushing of women.

With these rhythms, the dance becomes rebellious. The oppressed woman drops her scarf. The face-to-face meeting between her and the dancer testifies to the conflict between the desire for freedom and social constraints.

The grandmother makes a speech, trying to control the girl in the headscarf again. The young girls in the cell echo the grandmother’s sentences: they repeat them like a list of accusations. It’s as if they are trying to judge the grandmother, blaming her for their condition.

These women also express themselves through visually rich scenes. They lend themselves, for example, to a set of mirrors, playing with the pieces of polished glass that they hold in their hands. In another scene, they hold a white sheet which, under the effect of the lighting, reflects their silhouettes on a large screen. The play of shadows and lights gives access, in finesse, to the secret universe of these women who wash, wax, comb their hair, etc.

The scene of the grandmother’s judgment announces the end of the show.

Abdel-Fattah sums up his work with a scene of collages that bring together the choir singing, evoking the stereotypical speeches and the dances that symbolise the feminine condition.

The woman who has taken off her scarf heads towards the grandmother, but the latter disappears under her white sheet.

The outcome of the play is different to the 1990s version, where a young woman replaced the grandmother in front of the sewing machine. This time, apparently, there is a chance to escape the vicious circle.

Photo courtesy of ahram.org

This article was first published in Al Ahram Hebdo (issue 12 February).

For more arts and culture news and updates, follow Ahram Online Arts and Culture on Twitter at @AhramOnlineArts and on Facebook at Ahram Online: Arts & Culture

This article was originally posted at ahram.org on February 14th, 2020 and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by May Sélim.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.