The Greek philosopher Plato, summarized what is to be in love as “a serious mental illness.” Both a “rapture” yet also “pure madness.”

Love is the Pandora’s box of human existence and both heaven and hell are contained within it. Once opened, you will be forever changed. Of that there is no doubt. To dine in heaven or wine in hell, love has not changed since Plato’s time.

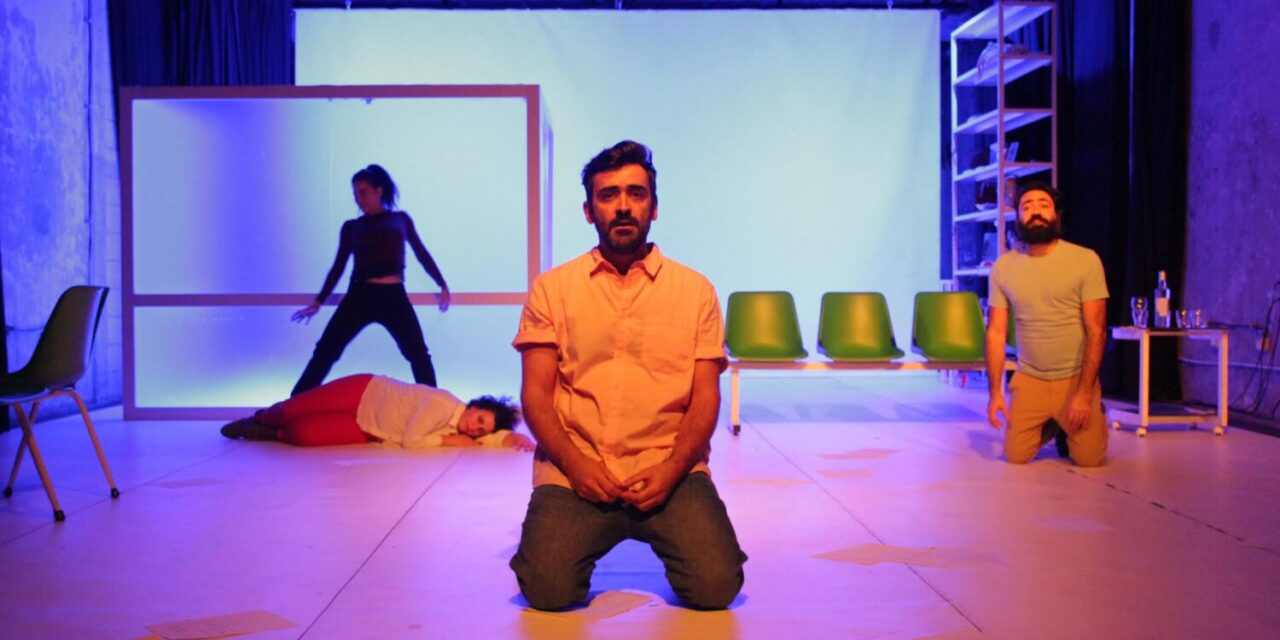

In these dark times where pandemic viruses are terrifying, economic collapse and poverty are rife, and the internet has made human relationships a hollow thing of the past, this Lebanese Theatre Company, Zoukak, has dared to study this conundrum of ecstasy we call “love.”

The Love Project studies a succession of ephemeral moments that have defined people’s various journeys. The play is based on in-depth interviews with people who shared their real love stories.

The audience are also participants in this study, researched throughout this wondrous play. They are engaged and challenged in ways they could not fathom whilst taking their seats. Zoukak explores the human “need” of love with its audience from the first innocent inklings of infatuation, through the finality of loss as the inevitable, final stage of love.

Photo by Mariane Kortbani.

The multiple stories form a journey where love between two human beings is both challenged and cleverly deciphered in ever changing monologues, with intelligence, sensitivity, depth and wit.

The seating is arranged so that intimacy between the cast and the audience is paramount from the start. The actors, Maya Zbib, Nasri Sayegh, Lamia Abi Azar, and Junaid Sarrieddeine begin reading sweet love letters to the audience. They engage them with deep eye contact, passion and heart; smashing down boundaries and intimately communicating one human being to another, soul to soul.

Each story is followed by a caress of lips, a whisper in the ear, a soft hand brushing across the hair of random audience members. Sayegh and Sarrieddine then expertly build on these themes with their next story. Senses are aroused and spirits engaged in a kind of “love spelt out for dummies” beginning.

The cast are playing out those innocent early days where interest and infatuation find their way coyly to becoming what we know as love. It reminds the audience of their own sensations of falling in love with one another; empathizing with them, in a shared human experience as far back as childhood.

The brilliant director Maya Zbib used food as a way of explaining some of the complexities of love. The audience is brought through the craving for a certain dish, to being totally full and utterly sick of eating the same thing, to craving something new and different to eat. The scene is subtle, profound, and extremely funny!

The actors’ improvisational skills are on display and do not disappoint. Inspired by the stories they collected during their conducted study, the cast adapts brilliantly, becoming the audience’s spokesperson.

Boundaries of time, language, age, sex, beliefs are seemingly cast away effortlessly. Love is of course intrinsic to all human beings. We know its seductive dance all too well; its beauty and its terror. The cast’s men mesh into a female role and visa versa, leaving no doubt in the audience as to the new transitions occurring.

Photo by Mariane Kortbani.

Homosexuality is still very much taboo in Beirut. The cast portrays same sex feelings in a society where they must remain hidden and never acted upon due to the fear of exposing these thoughts and feelings.

Lust or love? Heart or head? Realized or forever unrealized? There are impulses never acted upon and the effects of war and trauma are both real and invisible.

A broken heart added to a broken life can tilt the scales for many, who already are deeply intimate with post traumatic stress disorder and anxiety caused by war. Is love always the answer? In one breakup story Sarrieddeine returns to the fetal position in order to hide from the unseen storm all around. The hurt of ending a relationship with another of being all alone again in this place is agonizing. The audience can relate to his tortured torso. As we are led from an open relationship, to addiction, to devastating betrayal, this light breezy skip through the tulip’s view of love is very quickly severed and we see the lash of the whip upon spirits laid bare. Merciless and unrelenting in its barrage of pain, love is not painted fancifully or without illusion.

In a private room hidden away in the set, we are now whisked away to that place of body upon body and souls uniting in sexual intimacy. Two bodies make love for the first time in complete vulnerability. Nadim Deaibes’ sensitive and exquisite use of lighting combined with his technical design of the set, makes the journey and meshing of stories and concepts, an effortless transition. Scenographer Nathalie Harb leaves no stone unturned in creating an in-your-face reality TV show uncurling before the audience and cast.

The psychedelic techno hypnotic beat Ziad Nawfal lays down, manicures what’s already in place and gives the play a heartbeat. He adds his color and stamp, in the syndrome of ‘you are now moving as one’, that Louloua Ghandour adapts in her mesmerizing dance. Her movements are both strange and neurotic and a unique take on what this thing, this love, could be if given a groove to move with.

Photo by Mariane Kortbani.

Before the final scene, Zbib offers Sarrieddeine a gun, in what might equate to love being a suicidal choice. In the final scene, the actors both engage with and implore the audience to engage with each other. To look within the eyes of the one seated beside them, to tear up… to laugh… “Do not leave us” the audience is implored! “Do not leave us in the current crisis!”

As the Lebanese are indeed leaving the country for good, Zoukak is asking the audience to share one last dance. The conclusion offers a sweet dance between strangers who now share intimacy with each other. Ultimately, love is a dance amongst new found friends, a laugh at the end of a journey, and always the purest of virtues.

Edited by Heath Doolan

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Christiane Waked.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.