This conversation with Christa Sommerer focuses on some aspects of the gigantic artwork that Sommerer and Laurent Mignonneau have been building together since 1992. After a brief synthesis of their career, the conversation will address the relationship between the living and the artificial; interactivity, dynamic systems, and interaction, transmission through art, teaching, and coaching of young artists. Through the responses will emerge dynamics of affect and emotion, these essential fuels of art-making, before considering future trends.

Artist statement:

Christa Sommerer and Laurent Mignonneau are internationally renowned media artists working in the field of the interactive computer installation. They are professors at the University of Art and Design in Linz, Austria, where they head the Department for Interface Culture at the Institute for Media. For more than twenty-five years they’ve developed interactive artworks that have been shown all over the world and won numerous awards.

Artistic path:

Interactive art pioneers, Christa Sommerer and Laurent Mignonneau pursue careers as artists-professors-researchers. Their artwork, which has earned countless awards including two “Prix Ars Electronica”, has been circulating the world since Interactive Plant Growing, to more recently Egometer, and Neuro Mirror. At the heart of their approach is interactivity in all its forms, which promotes the dynamic encounter of the participants not only with species remotely located visitors but also with invisible energies. Playful and simple at first, each work reveals its complexity and innovation. By crossing old and new devices. Each work questions both our relationship to time, to the living, and the artifice in a changing world.

Affect and Emotion

L.B: To begin with, I would like to ask you this very simple question. What did you find in techno art that was not in your first career as a biologist, and sculptor?

C.S: When I studied botany, I always was very fascinated with the diversity and esthetics of plants. My preferred subject was nature drawing, and the botany teacher who taught this class told me I have considerable skills. However, he recommended that I not become too imaginative in my drawings but rather stick to the facts, and only draw what is there. Later, when I studied sculpture and installation art, I created a complex concept called Ikonophylla. The idea was to combine Carl von Linné´s plant classification system with sculpture. Again though, the sculpture professor told me that it was better to refrain from being too intellectual and conceptual, rather stick to a gut feeling – not to think too much. Finally, when I met Peter Weibel in Vienna in 1990, he told me to forget all I was told, and start to use the computer; This would be the ideal medium to combine botanical issues such as plant growth and diversification and combine them with my sculptural interest. He also told me to read Louis Bec´s writings on an epistemology based on Artificial Life and Technozoosemiotics. This greatly inspired me and I thought I should do something similar with artificial plants.

L.B: So, if you had only three words to pinpoint your artistic mission, which one would you choose? I say mission because it does not seem possible to last in this field and create so many artworks without a certain sense of belief, a projection in the future and a true desire to show and share these revelations with others.

C.S: Open artwork, interaction, user participation

L.B: Concerning affect and emotion, how would you spontaneously define and differentiate them?

C.S: Emotional impact is what we want to create for the users when they experience our artwork, affect is something more abstract, more like a strong feeling.

L.B: For example, when you dream about an artwork, conceive it, and realize it, what kind of force, quality and intensity (affect) do you feel in the process? Do you have examples to share?

C.S: Well in the case of the interactive art, for example with Portrait on the Fly, we wanted to create live portraits of people when they interact with their mirror image. But, when we found that we could use the motif of the fly to create these portraits, we felt a very strange sensation of fascination and disgust. The fly has so many meanings in human culture, there are so many proverbs and stories about flies. When we presented the final work, many people reported back having similar feelings about the flies.

L.B: This summer, I experienced Portrait on the Fly at BIAN-Automata in Montréal. It’s quite impressive but also provocative in this time of critical weather changes… During the whole process, from creation to the reception, what kind of emotions appear and orient your work?

C.S: As an artist, you have to be clear about what kind of emotion you want to evoke in people when they should experience your work. This emotion is also linked to a meaning or message – it should be experienced intuitively and non-verbally.

L.B: Would you say that your approach is rather intuitive, instinctive or linked with cognitive or psychological sciences or philosophical dimensions, if so which ones?

C.S: Yes, depending on the project, all these areas are relevant. We usually need quite a long research phase; reading, thinking, discussing, developing several versions of an idea, discarding them again, reacting to each other´s ideas, also fighting over some ideas. It’s usually quite a long germination process. But once we agree on an idea and both find it good, then we realize it, test it, adapt it, improve it, and present it.

Interactive Living and Aesthetic of Care

L.B: It seems that techno art has offered you a field of activity that blossomed your interest as a botanist or biologist, and as a sculptor. We would like to ‘hear’ you, if I may use this term in a written conversation, about the evolution of your interests as a biologist, then artist, teacher, and researcher. What drove you to all these activities? And how have they contaminated (in a positive sense) each other?

C.S: Well as mentioned above, I first studied botany and anthropology and then later modern sculpture and installation art. During my biology study, I was fascinated by the amazing forms in nature, the immense complexity of shapes and structures, species, families, and taxonomies. But I always had an artistic view on nature, I believe. During my sculpture studies, I worked with various materials such a plaster, marble, wood, polyester… but I felt that these materials reacted too slowly and it took too long for a single creation. I found these materials to not be flexible enough for the concepts I had. But once I discovered real-time computer graphics at Peter Weibel´s Institute for New Media in Frankfurt, and when I teamed up with Laurent Mignonneau, we began to work with generative processes and created artworks that deal with development, evolution, adaptation, and variation.

L.B: Twenty-six years later, Interactive Plant Growing is still fascinating. Not only does it allow for communication between participants and plants, but it serves as a dynamic mirror of multidimensions into aesthetic of care, plant vocabulary, syntax learning, and reflecting on invisible aspects of the relations between living species. During all these years, science has evolved and brought proof about what was before considered as intuitions, impressions or subjective feelings. How do you feel about that?

C.S: I think intuition is really important in human communication and interaction. Artists are very good at working with intuition and feelings, and one of the reasons why Interactive Plant Growing keeps fascinating the public is that it works with some very basic feelings we have towards plants. We know that they are alive, that they sense us, some people even talk to them, but we do not understand plants completely. We, humans, have a very strong symbiosis with plants – we need them, they feed us, we use them, but we also adore them, cultivate them and we have a strong emotional connection to them. This very special relationship we have with plants is something we wanted to address in Interactive Plant Growing.

Interactivity, Dynamic Systems, and Experiencing

L.B: Being at the heart of your artwork, interactivity seems to be not only technical but rather, suggesting a larger intention, such as a desire to facilitate participation in many different ways. Also, the span of the interactivity in your work has largely evolved not only in the variety of interfaces and devices but also like the experience that you proposed to the participants. From the beginning, viewers were exposed to plant growing with their touch, building dynamic portraits with their movements, inviting insects, flies, on different scales with dialogues and stories, and playing with ego and mirroring. How has interactivity evolved from 1990 up to now, and how did this interest last such a long time?

C.S: Interactivity for us is a means of getting people involved in the artwork. to achieve this goal we have created various interfaces, from plants to light detection interfaces, to 3D keys, to digital mirrors or sensing devices. The main objective is always to create an overall experience that allows people to intuitively feel, and reflect on the artistic message of the specific work.

L.B: With what criteria have you been constructing your interfaces? – from the beginning to more dynamic systems and remote locations.

C.S: In the 1990s there were very few commercially available interfaces, so Laurent Mignonneau made almost all of them by himself. He invented new interaction scenarios and even patented some of the interface inventions such as the 3D Key system for Trans Plant and MIC Exploration Space. Later, when interactive media became so popular, and when a “maker” culture and DIY community emerged, more interfaces became readily available. Sometimes we use more off the shelf technology if it serves the right purpose, but we have also still custom-made interfaces, like in Egometer. What we use or develop is always related to the specific art concept.

Artworks Generating the Most E-Motions

L.B: It seems that motivation, central in the etymology of emotion, is very important in all your work – In motivating a project, an experience, a connection, but also in student interests, knowledge sharing, and visitors of your artwork. Do you plan to produce specific effects or emotions with your artworks?

C.S: For each piece, it is quite a different emotion, but generally if the work is well designed, then the public intuitively understands what we wanted to say and convey. And what’s more, people usually find a lot of extra layers and meanings connected to their own previous experiences. It is a bit like in a wee-made movie: you understand the main message of the film, but everyone interprets it slightly differently.

L.B: Which specific artworks have generated the most emotional reaction? For you? And your public? Any kind of emotion, positive or negative, strong or weak…

C.S: The artworks which generated the strongest feedback, reactions, and attention so far are Interactive Plant Growing, Phototropy, A-Volve, Life Writer, Portrait on the Fly, and The Value of Art.

L.B: Do these emotions make you change your artistic intentions, and if so, how?

C.S: Yes, if we see that the artwork has not been fully understood or something is missing or if it turned out to be too complicated, we make iterations and adaptations. Sometimes we pick up an idea from previous artwork and develop it further in the next work.

Transmission to the Next Generations in Anthropogenic Time

L.B: Considering your books about art and science, interface and interaction design, interactive art research… but also about Wonderful Life, if you had to extract ‘un fil rouge’ (common thread) linking past, and the present up till now, what would it be?

C.S: The search for engaging the public into an artwork that is open and needs their participation. This is the common thread

L.B: As a teacher, what would you like to legate to the younger generations of students? But also, what do they bring to you year after year?

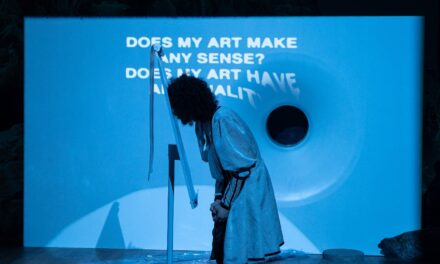

C.S: It is very inspiring to see art and media art through the eyes of young students. As our society has changed dramatically through ubiquitous media and social networks, we now face issues and problems that were not dominant ten to twenty years ago. What we want to do at the Interface Cultures program in Linz, is to raise awareness that we all have the power to change things for the better; it can be done by proposing artworks or prototypes that can become game-changers, or at least raise intuitive awareness about these burning societal and political issues.

L.B: As a researcher, what problems would you like to address for the next decades? Do you think that our time is critical?

C.S: I think now we need more critical investigations about the use of technology, and how it affects our social interactions and our environment. There is a certain need for critical investigations of interfaces. We need to look at what is hidden in and behind these black boxes that media companies provide to us, or even force us to use. From issues of manipulation to fake news, to issues of privacy and exploitation, there are so many issues that need to be addressed in the next decade.

L.B: In this anthropogenic era that the earth has officially entered, what may interactive do? Of course, art does not solve problems, but it certainly helps to sensitize people, to offer them a place to experiment, to get out of their envelope.

C.S: Yes exactly. Art can help raise awareness, make people understand complex topics intuitively, and also inspire them to develop these ideas further in their respective fields. It is already quite a good achievement if you reach this level of impact as an artist.

L.B: To conclude, how do you see the future of interactivity, dynamic living, and artificial systems?

C.S: Interfaces will become more and more transparent and hidden. The whole IoT industry is moving towards embedding sensors in any given object, striving for smart cities, smart homes, smart clothes, etc. Privacy, surveillance and data ethics will become huge topics. We as artists have to keep a critical eye on these developments and create our propositions and prototypes, raise awareness, ask questions and propose new metaphors and new memes.

This article was originally posted at http://archee.qc.ca and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Louise Boisclair.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.