The Korean theatre company ETS, which is an acronym for Eye To Soul, staged Charles Mee’s Big Love (2001) at the Haneul Round Theatre in Seoul, Korea, in June 2019 for the ten-year anniversary of the company’s foundation. Founded by four theatre artists (actor/writer, sound designer, lighting designer, and a multi-media artist) in New York in 2009, ETS has staged productions in South Korea, Scotland, and the U.S., under the artistic direction of Haerry Kim. Their repertoire includes socially-conscious original pieces such as FACE, a multi-media one-woman show about Korean comfort women, The Sound of Nightingales, about the rape and murder of eight Korean high school girls by high school boys in 2009, and I Love You After 4.16, about the sinking of Sewol Ferry which took the lives of 300 high school students and crew in 2014. ETS also presented several translations and adaptations of plays not widely introduced in Korea, including Aeschylus’s Prometheus, Martin Sherman’s Bent, and Günter Eich’s Sabeth. Since its foundation, ETS has created pieces with a commitment to fresh interpretation of social and cultural phenomena, professional actor training, finding innovative ways of communicating with the audience, and international theatrical exchange.

Big Love continues ETS’s introduction of lesser known plays in Korea, their reflection of social issues in their adaptation, and their innovative theatrical communication with the audience. Charles Mee is a widely recognized author in the U.S. for his radical adaptations of Ancient Greek classics, the sharing of his works in progress online, and the distinctive use of the stage, sound, video, and movement for Brechtian distancing effect, bringing attention to the socio-political and cultural issues and discourses. However, Mee is still almost a stranger in the Korean theatre scene. The only recent production of his was True Love, which was translated by Walter Byongsok Chon, and produced, under the direction of Kon Yi, at Jungmiso Theatre in Seoul in 2012.

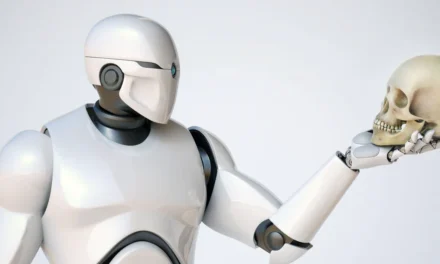

ETS’s Big Love at the Haneul Theatre. Photo: ETS Theatre Company

Mee’s Big Love, an adaptation of Aeschylus’s The Suppliants, portrays fifty sisters who flee to Italy to avoid being forced into marriage to their cousins in Greece. The play progresses with a trial about justice versus love, with tragicomic consequences. Mee modernizes the text through the use of both verse and prose and fast progression of the plot, connecting Ancient Greece to the present society as Mee saw it. ETS’s Big Love, directed by Haerry Kim, further brings the classic tale to the present by referencing the inflow of refugees from Yemen to Korea in 2018, raising questions about the clash between cultures and gender, and advocating feminism. The stage at the Haneul Round Theatre presents a square with only an empty bathtub, surrounded with two walls of glass doors and windows, with curtains drawn. While devoid of specific nationality, the design expresses refined European taste. At once, the space evokes the coexistence of public (square) and private (bathtub) realms and that of being enclosed (walls) and suspended (open area). Kim uses the performers’ bodies to their fullest extent, not only filling the whole space with dynamically choreographed ensemble movements but also, most memorably, having them continuously thumb their bodies on the floor, which generates a visceral response in the spectator. Even if the story might be far removed from Korea both in time and space, Kim’s deft direction and the performers’ fearless physicality offer a thrilling theatrical ride through Aeschylus’s story while illuminating how Ancient Greece, present day America, and Korea have commonly grappled with the questions of war and peace, domestic violence, gender and cultural politics, love and marriage, and the preservation and evolution of humanity.

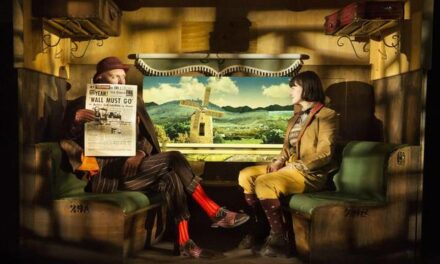

Poster for ETS’s Big Love at the Haneul Round Theatre. Photo: ETS Theatre Company.

The following interview with Haerry Kim was conducted via email in August 2019 and was updated in June 2020.

Walter Byongsok Chon (WBC): How did you come to choose Charles Mee’s Big Love for the ten-year anniversary of ETS’s foundation?

Haerry Kim (HK): Charles Mee’s plays are full of life and theatrical exploration. Especially, Big Love has a great combination of complexity and simplicity. These kinds of plays have not been widely produced in Korea, as most plays in Korea still heavily rely on realistic and plot-based narrative. With the kind of acting training I received at the M.F.A. Program in Acting at Columbia University, and being a Korean actor in New York City, the acting opportunities that opened up for me were mostly in experimental theatre. I am highly interested in finding new approaches to creating theatre. Experimenting with a variety of themes and forms will help theatre survive and thrive.

The structure and content of many commercial Korean plays are indistinguishable from those of TV shows or webtoons, with the only difference being the physical space of production. For the production celebrating the ten-year anniversary of our theatre’s foundation, the members and I read a bunch of plays and eventually picked Big Love. We believed that this play, even if it is an American play from 2001, speaks strongly to the Korean society today, and that its unique form offers something fresh to the Korean theatre scene.

ETS started in New York, with the one-person performance FACE, which was about Korean comfort women, women and girls who were forced into sexual slavery by the Imperial Japanese Army during the Japanese occupation of Korea. We produced six original plays and premiered new translations. Our original pieces include: FACE; The Sound of Nightingales, about the gangrape and burning that led to the death of high school girls in Bucheon in 2009; I Love You After 4.16, collected from stories about the aftermath of the sinking of Sewol Ferry in 2014; Bathtub Play II, a two-person play in English; And Bathtub Play: a Love Story, an experimental piece exploring love through memory and existence. We premiered the Korean production of Martin Sherman’s Bent in 2013. Up until then, homosexual characters were mostly portrayed as eccentric or funny side characters. There had hardly been productions, like Bent, with gay characters in the center. Bent received critical acclaim and was revived four times. In 2019, it was an official selection at the Seoul Performing Arts Festival.

ETS’s Big Love at the Haneul Theatre. Photo: ETS Theatre Company

WBC: What did you see in Big Love that could translate well to Korean audience? How do you see this piece speaking to the Korean society now?

HK: There has been an increasing demand for female voices in the Korean theatre scene, especially after the #MeToo movement turned the industry upside down. (The theatre industry was affected the most by the #MeToo movement, with scandals breaking about theatre veterans such as Lee Yoon Taek.) There has also been a drastic rise in immigrant population in Korea with the diversification of demographics. The constant decrease in birth rate has led to increasing demand of labor and productivity in the market. In 2018, about 500 refugees from Yemen applied for sanctuary in Jeju Island, and this issue received national attention. For the first time, the issue of Muslim or African refugee crisis was an issue of Korea, not just of Europe or the U.S. There are several connections between the socio-political issues portrayed in this play and what Korea has been going through recently.

WBC: Big Love is already an adaptation of Aeschylus’s The Suppliants, an Ancient Greek play from around 470 BC. What were some of the challenges in bringing to Korea a play that is twice removed culturally, from Ancient Greece to America to Korea, and originated in Ancient Greece about 2,500 years ago?

HK: Crossing the cultural borders and transcending decades and millennials did not come with any difficulty. We found, to our big surprise, how much the Ancient Greek play directly spoke to the Korean society of today and how well the American play from 2001 reflected issues that were pertinent in Korea, such as an updated version of feminism, the refugee crisis, and the various and violent methods of conflict resolution. That’s the power of theatre. I like Big Love because it explores and penetrates the human psyche. Coexistence requires communication and compromise, and progress requires risky undertakings accompanied with empathy, just like Nikos and Lydia’s plunge into the uncertain future in the end.

The audience had some difficulty with the form rather than the content. For example, when the dialogue was not realistic or coherent, when the brides or grooms were throwing their bodies on the floor, or when Bella holds the trial, audience members, who were probably expecting a realistic piece, wrote comments such as: “I don’t feel connected to any of the characters”; “I question the intention of the director for making the actors throw their bodies on the floor,” even though the stage direction specifies this action.; Or “A trial for the conclusion? What a terrible conclusion!” There are still many theatre goers who do not understand Ancient Greek plays or Brechtian plays and cannot accept anything but realistic and coherent plots. The lack of variety in theatre limits these patrons’ appreciation of theatre only to what they’ve been exposed to and what they are familiar with. This kind of atmosphere makes it difficult for artists to experiment. That’s why it is important to cultivate audience members to open up to new experiences, so that artists can try and stage more experimental works.

ETS’s Big Love at the Haneul Theatre. Photo: ETS Theatre Company

WBC: What do you think translations of Western Classics or foreign plays are bringing to the Korean theatre scene?

HK: It opens up new ways of thinking. We discover similarities in human situations. But because of history and the socio-economic environment, people don’t think that there are other possibilities to solve conflicts. Theater from different times and cultures shows us it is feasible to think differently and make different choices. I think diversity is a key to make theater useful.

In terms of classics, I think they open up one’s perspective. We are confined and isolated in this age of technology as much as we are exposed to enormous information. I believe great classics, it doesn’t matter Western or Eastern, bring us back to the important question of who we are and how we want to live.

WBC: What would you like to see more in the Korean theatre scene? New voices? Revivals? New forms? Or new practices?

HK: Everything. I really hope to see an eclectic mix of diversity in forms, practice, and voices in Korean theater. Korean audience definitely needs to be exposed to more various forms of theater. It will transcend the way they engage with theater productions.

In Korea, there is a term called “corpse watching” (시체관극). Some audience members consider themselves aficionados in theater, and they insist that everyone should be extremely quiet and immobile in theater. People feel forced to be like corpses in theater. Even with Big Love, there were people complaining about other audience members laughing during the show. It’s completely irrelevant. Theater needs to engage and stimulate the audience in many different ways. We definitely need more changes.

ETS’s Big Love at the Haneul Theatre. Photo: ETS Theatre Company

WBC: Could you briefly share what your next projects are? What are you most excited about your next projects?

HK: I am creating a new theater piece about my mother. She suffered from Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s for over ten years. It was very slow and painful to witness. She was unable to move or speak for eight years lying on her bed. It forced me to reflect on death, memory, and life. She was present but gone at the same time for those eight years. I want to retrace her lost memories and how that affected my life while she was in her bed. I want to experiment with visual images of my mother, her grandchildren (my nieces and nephew), and all the paper works I had to fill out from her diagnosis to her cremation. That experience covered a quarter of my life.

Currently, I am working on a new play called N Virus Project. The first workshop performance is on the 27th of June, 2020. It is about the biggest on-line sexual exploitation case in Korea. In February of 2020, the South Korean police investigation revealed that 260,000 users were in telegram chat rooms called the “N Rooms” exchanging sexually exploited videos of minors and women. This shocked the Korean society and caused public outrage. I have been working with a group of mostly female actors to develop a play about it for the past three months. I will continue working on this play and complete it by next year.

WBC: Thank you for sharing your thoughts! I look forward to seeing your next pieces.

Haerry Kim. Copyrights: Haerry Kim.

Haerry Kim is an actor, director and Designated Linklater Voice Teacher. She holds an MFA in Acting from Columbia University where she studied with Kristin Linklater from 1999 to 2002. As an actor, she performed in New York and various cities in the U.S. as well as other countries including Germany, South Korea, Switzerland, France, Belgium, Netherlands, and Norway. Some of her theater acting credits include the world premiere of All is Not by Melisa James Gibson, Songs of Dragons Flying to Heaven by Young Jean Lee, Alma in Summer and Smoke at the Seoul Arts Center (national theater), and Richard III directed by Andrei Serban. FACE, her one person play about Korean comfort women during the World War II, was performed in South Korea, United States, and Scotland with critical acclaim. Most recently, she played Soyoung in the film Spa Night, which was in the U.S. dramatic section at the 2016 Sundance Film Festival. The film also won “John Cassavetes Award” at the Film Independent Spirit Awards in 2017.

She is currently the head of the theater department at Kookmin University in Seoul, South Korea. She is the artistic director of ETS theater company in Seoul. Her directing credits include Prometheus, FACE, I Love You: After 4.16, BENT, Richard III, The Hothouse, Bathtub Play, Sabeth, Big Love, and The Sound of Nightingales. She taught professional voice classes at the National Theater Company of Korea, Myeong Dong Art Theater (National), Seoul Art Center, Seoul Theater Center, and various professional theaters in South Korea and Taiwan.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Walter Byongsok Chon.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.