Muriel Heslop occupies a precious position in Australian cultural life. She is, perhaps, our most-loved dag. The creative team that has transformed her story into a musical have produced a deeply satisfying night at the theatre. Any moment of translation carries with it the possibility of disappointment and betrayal. But the Sydney Theatre Company’s Muriel’s Wedding: The Musical makes us fall in love with this story all over again.

Muriel’s ABBA-propelled journey burst into Australian cinema in 1994 as part of a cultural moment in which Australian quirks became the object of tender and loving laughter on the big screen (alongside Priscilla: Queen Of The Desert and Strictly Ballroom). She is the last and most challenging of this trio to be given the musical treatment –perhaps because the emotional landscape of this story is a little more complex.

The main contours of the plot remain the same on stage as they did on the screen, though the action has moved into the present. The totally daggy and ostracised Muriel is trapped in Porpoise Spit where she listens to ABBA and dreams of a wedding where the popular girls and her family will finally see her as a success. Rather than meeting her true love, however, Muriel meets Rhonda–another outcast with whom she escapes to Sydney.

Freed from the judgemental gaze of her father and supported by the carefree Rhonda, Muriel transforms herself into the story she always wanted. The truth of her past life and the reality of her current one, however, soon impinge on this fantasy world to make it unsustainable, and Porpoise Spit begins to exert its influence on her once more.

While satirical, Muriel’s Wedding also has a deep vein of sadness. The Heslops are a family bullied and belittled into misery by a boorish patriarch, Bill. I was a little nervous about how Kate Miller-Heidke and Keir Nuttall would engage this complex interplay in their music and lyrics; they have managed to keep the balance between these sensibilities without ever teetering into melodrama or cliché. The writing is whip-smart and completely loving.

As in the film, ABBA’s music still provides the backbone to Muriel’s story of herself and now, crucially, her mother. Miller-Heidke and Nuttall have masterfully woven various ABBA songs into their original music and lyrics. When Muriel retreats to her inner fantasy world, ABBA burst out of cupboards or through shop windows to narrate Muriel’s story to herself.

Maggie McKenna’s Muriel makes us fall in love with her all over again. So too, Madeleine Jones’s Rhonda is the kind of friend we all wish could deliver us from the limitations of how we see ourselves. The love song, You’re Fucking Amazing, sung in thick Australian accents between this pair in the first act, is an anthem to the pleasures and potency of female friendship. This is friendship as revelation and savior. It is mateship with a feminist sensibility.

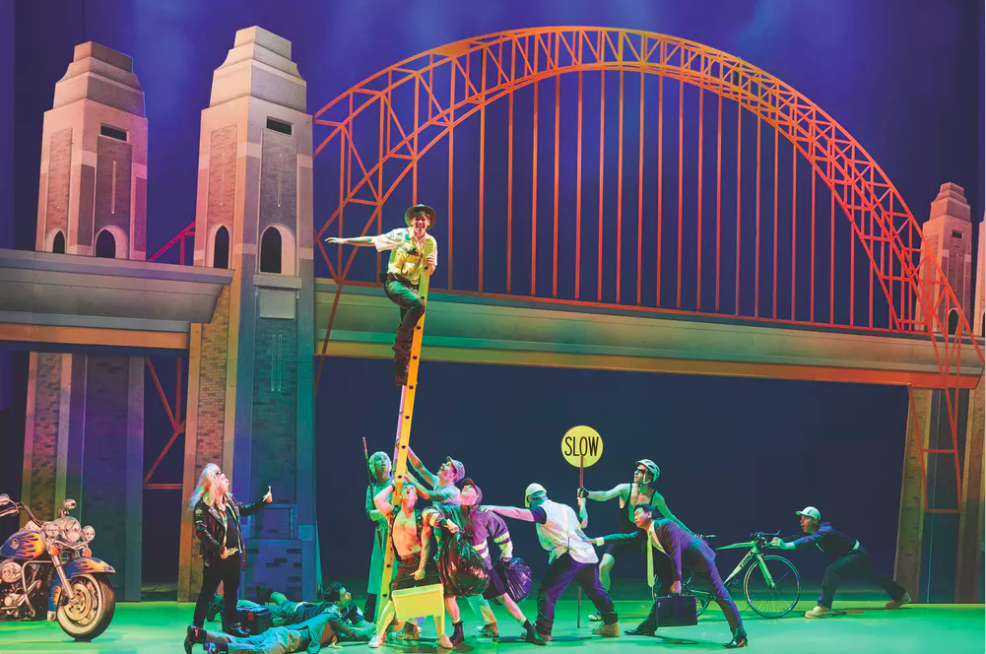

Stephen Madsen as Alex. © Lisa Tomasetti

Indeed, the beautiful irony of Muriel’s story is that–in the film at least–she essentially ends up with her female best friend rather than the bloke of her imagination. While the musical does maintain the centrality of this plot, it amplifies her romantic coupling at the same time. To my mind, this dulled some of the power of the story.

The production also provides the deep pleasures of recognition as these caricatures of Australian life are given the musical treatment. The audience positively shivered in pleasure when “you’re terrible, Muriel” is uttered by Muriel’s sister and roared with laughter when Tania screeches “but I’m a bride.” (Tania is played with scene-stealing presence by Christie Whelan Browne who manages to burst out of the long shadow cast by Sophie Lee’s filmic performance).

By moving Muriel’s story into the present, her feelings of inadequacy and hopes for reinvention intersect with the psychological death trap of social media. Popularity, which in a 1994 story was as much a feeling as it was a quantifiable reality, is now something that can be tracked through “reposts” and “likes.”

The musical is also a love song for Sydney. When Muriel escapes her family and friends in Porpoise Spit, she arrives in a city in which it is possible to “be the me” she wants to be. Sydney has long enabled this kind of remaking of the self–not least because queer life is part of the city’s DNA.

The musical makes queer Sydney into a more central part of this story; the streetscape of Sydney on this stage is full of same-sex desire and one character (not who you might expect) comes out in a set of delightful plot turns in the final act. Given the ways in which the same-sex marriage postal survey revealed divisions in support across Australia, it is hard not to read this musical as a gentle critique of the stubborn phobias and prejudices that still dominate in some parts of the country.

The Cast of Muriel’s Wedding: The Musical. © Lisa Tomasetti

However, while Bill Heslop’s battler is the object of savage satire and critique in both the musical and the 1994 film, comfortable cosmopolitans might do well to remember that the “battler” was key to former prime minister John Howard’s election in 1996. Many people felt alienated from what they perceived as an urban-centred cultural and political elite. The stories we tell about these differences have the capacity to entrench or undo these perceived divisions.

Rhonda and Muriel escape back to Sydney at the end of this story, which left me with some questions about how this musical might play on stages outside this city. A Sydney audience is probably pretty ready to watch a story in which their city becomes a haven for the marginalized. But I wonder how people in those apparently stultifying communities will feel about having their homes reflected back to them as sites of oppression.

Muriel’s Wedding: The Musical is showing at Roslyn Theatre until January 27, 2018.

This post originally appeared on The Conversation on November 22, 2017, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Leigh Boucher.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.