Sam Mendes–Oscar-winning Sam Mendes (American Beauty [1999])–has confirmed it: in 2018, he will be staging his own take on Lehman Trilogy, a three-part play by the Italian playwright Stefano Massini about the rise and fall of the multi-billion-dollar corporation Lehman Brothers. The latter event, as we know, shook the foundations of the global economy in 2008. And that was reason enough for Massini to write a play about Lehman Brothers: about a titan considered “too big to fail” which, left to its own devices, went on to prove that such a label was (and still is) nothing more than a reassuring self-delusion for the masses.

The play made its debut in France (Arnaud Meunier, 2013) before its official staging in Italy, in its homeland. And it is on this first, prestigious Italian staging at Milan’s Piccolo Teatro (indeed, the theatre’s crown jewel from two seasons ago) that we will be focusing on in preparation for Mendes’ debut: Lehman Trilogy as staged by the late master Luca Ronconi (1933–2015). Lehman Trilogy as the last, great work of an Italian theatre authority of the utmost importance before his demise.

To narrate the story of Lehman Brothers, Massini chose a prosimetro, a harmonic mixture of prose and poetic verses that rolls off the tongue like an obsessive lullaby. It represents 150 years of American social and economic history, summed up through the exploits of a single enterprise (and, indeed, a single family) and forged into a ballad [1] of reiterated formulas, of returning patronymics and insistent terminology meant to suggest an ancient Greek epic.

And the tragic, hubris-fueled ending is a given. Or, at least, it would be if the play ever gave in to despair, abandoning Massini’s dry-witted rhythm–a musical flow sometimes bordering on the upbeat, captivating enough for Robert “Bobbie” Lehman (Fausto Cabra) to keep dancing a frenetic Twist up to his death of old age.

His and that of Lehman Brothers, of course.

Even more important than the Greek influences are the Semitic ones. The entire play is scanned by Jewish traditions, enhancing its ritualistic and ever-returning qualities: the roots of the imposing Lehman tree dig deep into Ashkenazic Judaism, into Talmudic principles of work and dedication. It is under these rules that the first Lehmans thrive and prosper; it is by forgetting these very rules and giving in to their passion for money and immateriality that the last Lehmans fall, leaving behind the withering husk of an enterprise which will soon be lost to time.

When capital takes hold, the Lehman world (elitist mirror of that which surrounds it) becomes too crammed with money for feelings to properly enter it.

“Egregio padre,” “Egregio figlio” (“Father, Esq,” “Son, Esq.”): the characters no longer share affectionate relationships. They are merely colleagues, successors, weak links in need of strengthening. The passion for Lehman Brothers is an all-consuming one, one which does not admit other endeavors. [2]

The stage, much like the Lehman enterprise, is covered in signs, headlines, writings–the marks of Lehman Brothers’ passage through history: from the humble, hand-painted sign posted above Henry Lehman’s (Massimo De Francovich) shop in Montgomery, Alabama, to the Liberty-style golden letters towering over Lehman Brothers’ headquarters in New York. Words mark the rhythmically mesmerizing foundation of the play, largely devoid of action, per Massini’s visceral writing; words are all that is permitted to the scenic design, too, per Ronconi’s profound minimalism. The actors (echoing, intersecting voices and presences which remain onstage long after the passing of their characters) make the writings their foothold for greatness, marching over them as they let out their lines–words floating over words–in a sleepwalking fashion.

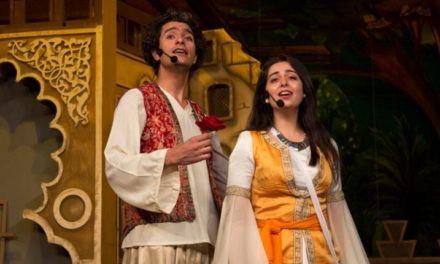

Lehman Trilogy, photo by Attilio Marasco. Joining the actors from the featured photo is Fabrizio Falco (center).

Sleepwalking, indeed. And dreams, dreams, dreams: haunting each and every Lehman householder with apocalyptic visions of towers too high not to collapse, babelic structures which graze the sky and yet are doomed to come crashing down. [3]

The victims of such generational curse, Atlases bearing the weight of the world, search countless ways to get rid of them, shaping the global economy in the process–and ultimately dooming it to crisis when the titanic automaton they have created out of nowhere is left to walk without a head, the last Lehman having met his demise.

Lehman Brothers falls, bringing a large part of American and world history with it. And the spirits of the Lehmans, having awaited the announcement in an afterlife looking like a Board of Directors, mourn it.

In the end, they resume the Old Ways they had forgotten.

Lehman Trilogy, photo by Attilio Marasco.

Notes

- The term Ronconiused to describe Massini’s work and to refer to the form of a ballad he sought to adhere to in his play, which Massini himself (who succeeded him as Piccolo Teatro’s artistic consultant) had a part in staging.

- A mild exception being the various attempts at marriage. Characters choose a wife in different, usually amusing fashions and eventually get married, but their clumsy and lovable attempts are left out of the play as soon as they accomplish their goals. Women give birth to Lehman successors, to those meant to inherit the enterprise and further the narration, and then they slowly fade away. When we next find them, they are already dead and easily forgotten: they “rest under a slab of marble,” unable to lend a helping hand to their husbands. Bobbie Lehman’s relationships are yet another exception, but hardly a positive one: he divorces his first two wives, unable to properly relate to them, and passes away before the third.

- Afraid of fast-moving, uncontrolled trains–standards of a roaring new age–bursting into his empire of cotton and coffee, Emanuel (Fabrizio Gifuni) covers America in a complex network of rails, exorcising his old-timer fear of things to come. The concerns of his heir Philip (Paolo Pierobon), as much a son of modernity as he is his father’s, lie in the Stock Exchange, that same immaterial mechanism whose creation he has directly contributed to: a balloon which is bound to burst, carrying with it the hopes of a naive 1900s America and bringing down the gargantuan sukka (ritual shack) which Philip tries to build every night in his dreams. Bobbie is tasked with collecting the pieces. And he succeeds, fighting off one by one the ghosts which haunt his sleep and keep changing form: whether collapsing towers of suitcases and telephones or a gargantuan King Kong which can only be killed through the use of an “exceptional sling,” “one with a capital S”–an atomic bomb.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Davide Cioffrese.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.