Image: David Caines Unlimited. Courtesy of the artist and the curator of the exhibition.

“Downtown Manhattan, 30th September 1978. Tehching Hsieh, a young Taiwanese artist, begins to make an exceptional series of artworks. Working outside the art world’s sanctioned spaces, Hsieh embarks on five consecutive year-long performances. He starts each work by releasing a statement: a strict set of rules that will govern his behavior for the entire year. These performances will be unprecedented in their use of physical difficulty over extreme durations; they will also be unyielding in their conviction that art is a living process.

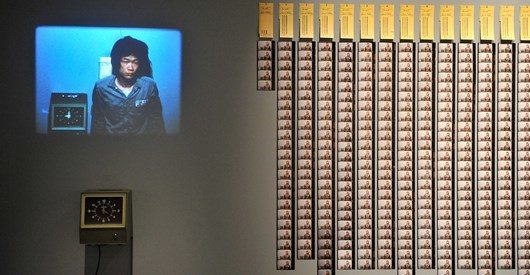

Doing Time exhibits two of Hsieh’s One Year Performances together for the first time, assembling his accumulated documents and artifacts into detailed installations. In One Year Performance 1980-1981, Hsieh subjected himself to the dizzying discipline of clocking on to a worker’s time clock on the hour, every hour, for a whole year. In One Year Performance 1981-1982, Hsieh inhabited a further sustained deprivation: he remained outside for a year without taking any shelter. Each work convenes different methods of documentation, challenging what it might mean to archive a life. Together these monumental performances of subjection mount an intense and affective discourse on human existence, its relation to systems of control, to time and to nature. Hsieh’s fugitive presence – traced throughout – speaks both of the abject conditions and ingenuity of survival for those who have nothing. During the course of his One Year Performances, Hsieh was an illegal immigrant.

The final room of Doing Time takes us back to three of Hsieh’s previously unseen works: short performances and photographs, all made in Taipei in 1973, before his emigration. At the close of the exhibition a documentary, Outside Again, returns Hsieh at the age of sixty-five to the original sites of his performances in Taipei and New York, making a meditation on the resonances of these far-sighted works.” (excerpt from the e-brochure of the exhibition, courtesy of the curator.)

(Ths interview is conducted on June 22nd at Mr. Hsieh’s studio in Brooklyn, NY)

KaiChieh Tu (KT): Why does this Venice exhibition titled “Doing Time,” as opposed to “Passing Time” or “Wasting Time”? ‘Doing’ seems to suggest a more active sense.

TehChing Hsieh (TH): We thought it’s a good title. I think “Wasting Time” could be more ‘individual’ and subjective. Passing time is something everybody could do. My performance work shows different perspectives of thinking about life. But these perspectives are all based on the same precondition: “Life is a life sentence. Life is passing time. Life is free thinking ‘ Doing Time’ in this sense is more appropriate.

My art is pure ‘passing time.’ Art is a dialogue with audiences. I use art forms to question issues related to the human condition. If the artistic values or aesthetics are of high quality, viewers can reflect on their own lives and perception of time, life, and existence.

KT: Do you still allow yourself to see and experience art after you declared you’re no longer an artist?

TH: I don’t really go to see others’ art work. I will go if I have to. But of course, I was influenced by other artists’ aesthetics. Anything could influence me very easily.

KT: Has your life completely changed after you declared you’re no longer an artist after Thirteen Year Plan in 1999 ( ‘Thirteen Year Plan’ was the period from 1986 to 1999 where he announced he would continue to create art work but would not show it publicly)?

TH: ‘Doing art in art time’ and ‘doing life in a life time’ are not so different. The difference is that I don’t use art form anymore.

KT: How do you distinguish between life time and art time?

TH: Art time and life time is the same in the sense of passing time.

But there is always a paradox. They are different in the sense that every day is different, every second is distinct from the last second. There is no turning back.

Also, when you want to establish the rules for a game (in this case, my art), you unavoidably have to make a distinction. My work has everything to do with time. So it’s important to mark the beginning and the end of my art time for practical reasons.

I want people to understand my art work has life quality. Doing art is art time, and the gap between two pieces is a life time.

KT: But there was no difference between life time and art time during Thirteen Year Plan?

TH: It was blurry at that time. I was still doing art, but I couldn’t publish them. I still marked this period as my art time, although it was challenging to separate art time from life time. One year performances were more ‘compressed’ in a sense. The concept of Thirteen Year Plan requires more than one year to realize, so it was much more diluted. It took more than a decade. My work became life.

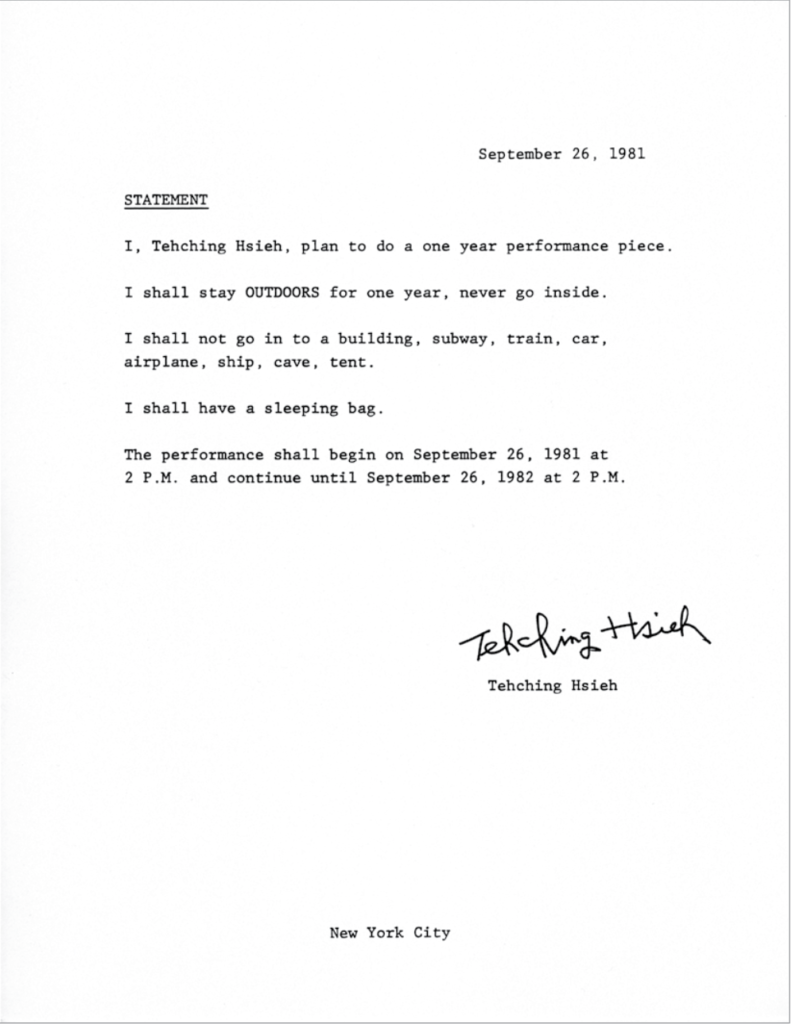

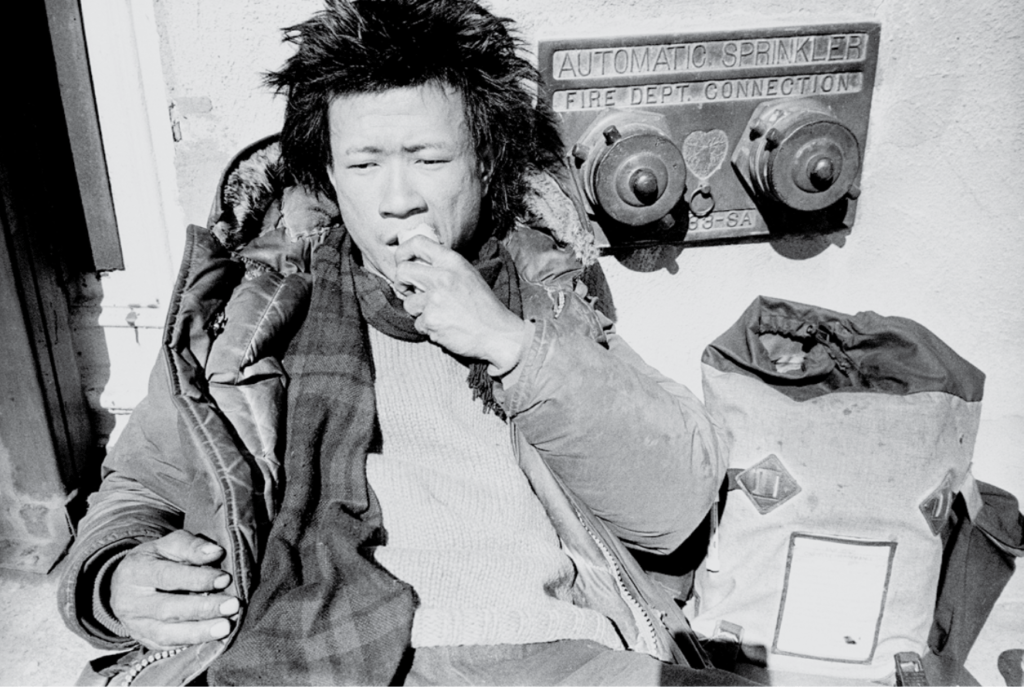

Tehching Hsieh, One Year Performance 1981-1982. Performance, New York. Statement, paper, 8.5 x 11 in (21.6 x 27.9 cm). © Tehching Hsieh. Courtesy of the artist, Gilbert & Lila Silverman and Sean Kelly Gallery.

KT: Why thirteen years?

TH: It was 1986 when I started, so it was 13 years before the end of the century. Before this, I just had a one-year No Art performance (1985-1986 he decided to stop doing art for a year), so I couldn’t possibly go back doing art. Also, my birthday is December 31st, so I decided to start the performance on my 36th birthday and end it on my 49th birthday, which was also the last day of the 20th century.

KT: It feels like there is always a paradox, a contradiction in your work.

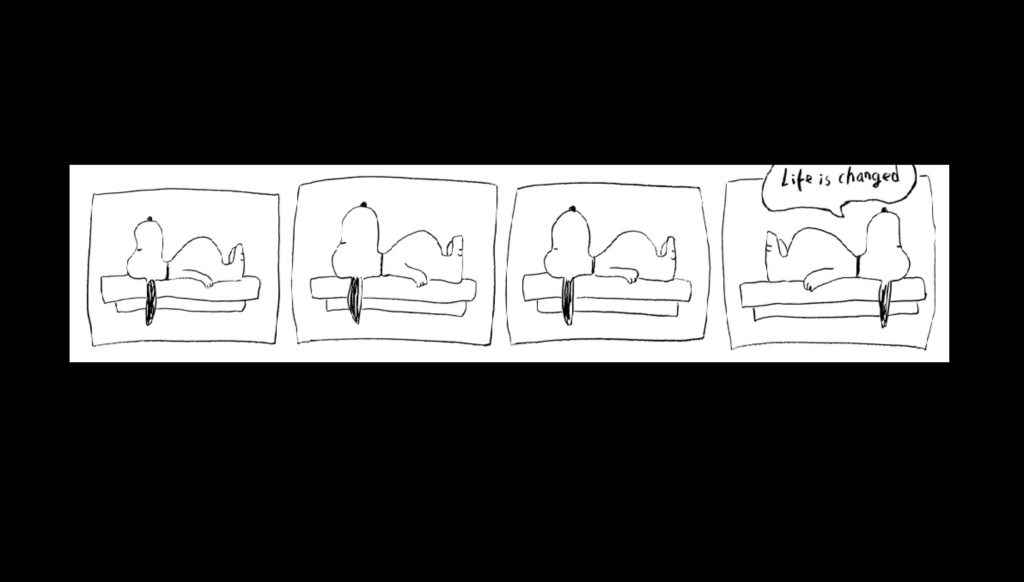

TH: Let me show you something. Life is like this Snoopy. Do you think things have really changed for him? But this meaningless change is crucial for our lives. We are obliged to pay attention and take care of details.

KT: By ‘details’ you mean trivial matters?

TH: Yes. Like in this cartoon, we care about this ‘change.’ Even though I’m aware of it, I’m still subjugated to this law. Without this comfort, you won’t know how to live. The big premise remains, but small things matter to us, albeit we are aware that they don’t change anything. The so-called eternality is, in fact, something lasts a bit longer. For example, the sun is eternal for us. But it’s ephemeral for the universe.

KT: You had a very complicated relationship with the law as an undocumented immigrant back then. You wrote statements and ‘contracts’ before your projects started. What do ‘documents’ mean to you in your work?

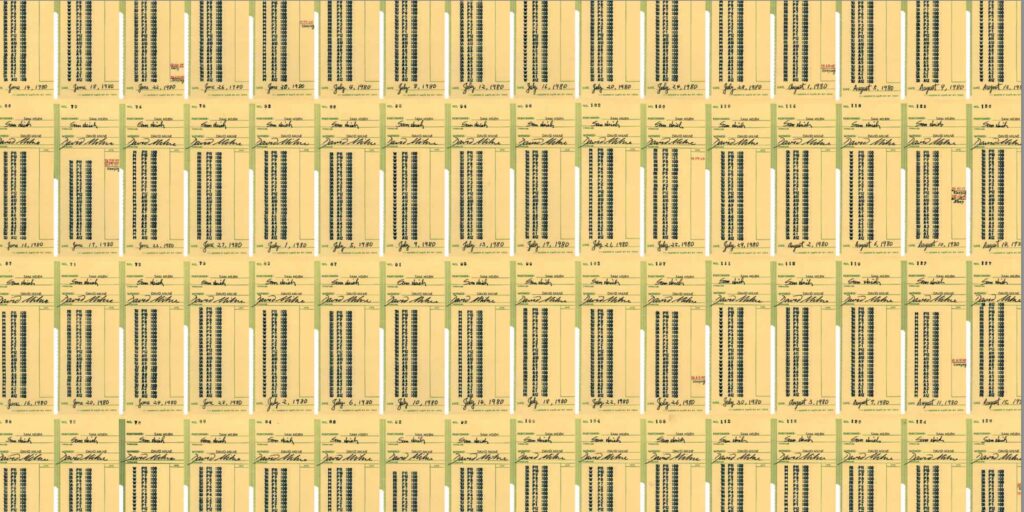

TH: When my performance work passed, it’s gone. Documents help preserve some elements and moments of my art. But they are more like sub-art for me. I don’t want people to think the documents are the biggest part of my work. Like the map I’ve drawn (Outdoor Piece, 1981-1982) and the cards I’ve punched (Time Clock Piece, 1980-1981)…the maps were drawn to track where I slept, ate and went..It was like putting a GPS tracker inside an animal’s body. But that’s all. Or the daily selfies I took (Time Clock Piece).. my hair and look changed as time went by. It was a proper way to visualize the passing time and the paradox that everything changes but also remains the same.

KT: There were some empty slots in those punch cards? Why is that?

TH: Those were the hours I missed punching the clock. I chose to present the moments I failed to follow the rule. I missed 1.52% in total. I slept through for 94 times, and I was late for 29 times, early for 10 times.

Tehching Hsieh, One Year Performance 1980-1981. Performance, New York. Time Cards. © Tehching Hsieh. Courtesy of the artist and Sean Kelly Gallery.

KT: Speaking of breaking the rules, could you talk about the incident you were involved in during the Outdoor Piece? You were forced to enter an indoor space (the rule you set for this piece forbade you entering any indoor place for a year). What happened?

TH: It was an accident. I got into a fight and was arrested by the police. Yes, I broke the rule. It was a very serious situation because I could have faced jail time and deportation. I was dragged into a prison, captivated for 15 hours. It was not an ordinary indoor space. The meaning of this incident thus got more complicated, aesthetically or thematically.

KT: Could you talk about the ‘contract’ you wrote for yourself before a project started?

TH: In real life, I was an illegal subject. In art time, I used legal language to make statements and I had lawyers or art directors as my witnesses. This method gave my art authenticity and trustworthiness.

KT: Were there any room for dialogues with audiences or people during one-year performances?

TH: It was difficult. I isolated myself during the performances. Direct communication with the audiences was not my priority. They were witnesses.

KT: But you had open hours for audiences to visit? How about the Outdoor Piece where human encounters were unavoidable?

TH: Yes, I would have open hours, the Cage Piece for example, for people to visit. But I won’t talk to them. For the Outdoor Piece, I had one poster made every season that indicated different locations and times where I would appear. I stayed alone most of the time. I looked just like a homeless person so it wasn’t an issue for me.

Tehching Hsieh, One Year Performance 1981-1982. Life Images. Performance, New York. © Tehching Hsieh. Courtesy of the artist, Gilbert & Lila Silverman and Sean Kelly Gallery.

KT: Your work (or more appropriately, ‘unwork’) is often described as the performance of withdrawal—withdrawal from constructed indoor places and architectures, from productivity and capitalism ideologies, from globalized, regulated norms of living and survival, from making or producing art capitalized and labeled by the public and market. Would you agree?

TH: My work is open to interpretations. But personally, I’m more interested in philosophical aspects. I am not talking about ‘how’ to passing time, but just passing time. I do not intend to change the world.I just reveal the relationship between life and time.

I don’t really use words like capitalism or globalization. I am from a more primitive perspective. I did art and performance first before I understood the art world. I did it first, then people responded, and then I responded back. That is my way. I don’t have too many tools to know the whole history of human civilization…I’m primitive, but my primitive is not unrealistic… I mean, look, I came to New York! At least you need to know your direction.

KT: Do you feel this action of withdrawal has liberated you from the society and given you freedom of thinking and living, as you said regarding the Cage Piece: “I am as free in the cage as outside… my work here is… focusing… on freedom of thinking and on letting time go by.”?

TH: The ‘withdrawal’ did not give me the freedom to escape my reality. I still had to pay my rent and feed myself. There was no actual withdrawal whatsoever. The action of withdrawal was planned and orchestrated. I was a performer. My performance was superficial, my reality was still real and did not change in my art life. That said, my perception of time has changed and freed in a way after doing all the durational performances.

KT: Do you feel the world is a different place now, compared to the 70’s or 80’s? Do you feel, as in 2017, there is a different force and system to fight against, a different way of self-expression, a different philosophy of survival, a different perception of time? Would you say it’s better, worse, or always the same? How did ‘wasting time’ come to your art and life? Was there anything specifically that brought the concept to you?

TH: To me, it’s the same. Whether you waste the whole year or you’ve achieved a fulfilled and contented year, it’s all the same. Because you just pass the time. It’s not the question about ‘how’ to pass the time. Just passing time. This is my philosophy. You see, tons of talented artists out there, and I thought of myself as a talentless idiot.. but then I thought, my talent is wasting time. I’ve achieved something great in this field. I told myself that. No one is going to compete with me on wasting time. Well, maybe those homeless people.. but that’s their real life. But for me, it’s different because I live in art and a concept. I execute the concept. Of course, my life aligns closely with my art and action. But there is still a distinction. I still have my life and moments of not wanting to waste time. It’s still my choice. People often ask me, “why do you have to take so much time for just one piece of art?” In the Eastern world, people tend to think of this concept as “wasting life.” For me, this concept of wasting time encompasses more philosophical questions than the notion of ‘wasting life.’

KT: So do you think ‘wasting life’ puts more emphasis on individuals and human lives themselves, whereas ‘wasting time’ enriches your concept more by including the broader universe and mysterious cosmos?

TH: Yes, it’s more comprehensive in this sense. That’s why I don’t think there is much difference between 70’s or 80’s and now. I don’t think that way.

KT: Since we’re on this, I am very interested in your thoughts and philosophy of history. One can argue that your (un)work charted the alternative history of human existence and passing time. Do you perceive human history a line, a circle, chaos, or something else? What are the relationships between charting down your bio-history (for example, you marked down in detail your daily routes and biological activities on maps during the Outdoor Piece in Manhattan) and the history of all humankind?

TH: The big premise doesn’t change. I think most of the human history is more like a line. I think the concept of chaos is very interesting. We can only start to fathom the idea of chaos when we consider everything in the whole universe. Human beings can’t understand nor take the sheer scope of the cosmos. We are trivial. The unknown also puzzles us. The concept of time also changes completely in the space. It’s not a line. We have to bend the time to travel to another planet. Human history means nothing to the universe. Some empires have arisen and some empires have fallen. But it’s still within the scope of human activity.

When I first got to New York, I was looking for inspirations for projects (before one-year performances), I did a lot of free thinking, trying to come up with what and how to create: where do I find the energy and motivation for creation? I was on the edge of breakdown because I was thinking way too hard and way too long. I encountered enormous obstacles in New York City. But it occurred to me out of the blue that everything made sense. It was like time made a turn in the straight line, I suddenly realized that I was already in my work. I came here in 1974 and I did my first piece in 1978. I wasted four years. I’ve spent four years just thinking. But that had already become part of my work and life. Me wasting time and thinking. That was already the performance.

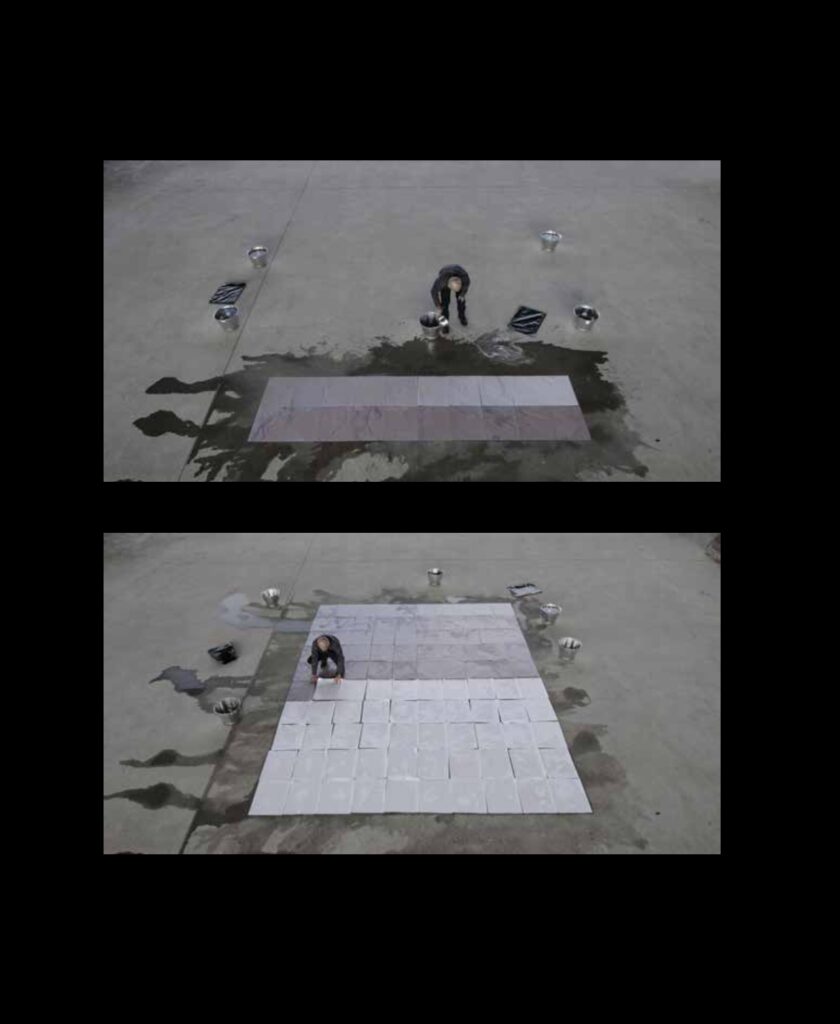

Tehching Hsieh, Exposure, 2016. Video still of performance, Taipei, 2016. Director of photography: Hugo Glendinning. Curator: Adrian Heatheld.

KT: So do you think without these four years of wasting time, your work wouldn’t have been born?

TH: Maybe, maybe not. You know it’s a terrifying thing to waste your prime youth from age 24 to 28 without creating any concrete work. As an artist, it was devastating, and it seemed there was no hope. But sometimes it only takes a ‘thought detour’ in a blink of an eye to completely alter your perception and reality. I was already in my art when I was struggling and thinking.

KT: Why did you choose one year for your projects? Does it have any significance?

TH: I want to talk about life, the intersection between life and universe. One year relates closely to this intersection. For me, I think it’s a beautiful rhythm to art and life. It’s a repetition. But it’s also different—every second, every hour is different. There’s no going back. But paradoxically, we are doing the same thing over and over again.

KT: Could you talk about your plan to realize your whole art life including Thirteen Year Plan? I know you’re thinking about five rooms to exhibit your previous work, and then 13 empty, identical rooms to embody the spirit of Thirteen Years Plan.

TH: I had this idea in 2000 when I had a chance to do an exhibition of my lifework. Because, as you can see, my two last projects have very little documentation and materials. I can’t just put them in a museum because the lack of visible elements would be a misrepresentation of their weight and time in my life. So I transform time into space. I don’t want people to think that my documents are my art. I want people to think that time is the most crucial element my art. But in a museum, space is the language. So I want to convert the time into space by creating those empty rooms. But of course, it hasn’t been realized yet.

No matter how much documents I have for a piece, they will take up the same space. I want to showcase the idea that one year is one year, no matter you waste or fulfill it.. the quantity of life is the same for everybody. One year means the same for a king and a homeless person. There is no difference. Whether I’ve documented a lot or not for a piece, the time I spent is the same.

Every room is the same size. My art is action, is ‘doing,’ not those documents. It’s not about the quantity of the papers. I want to convey the central concept that my time has been exhausted. There are layers to it, though. Are you just wasting time? Or are you producing stuff? For example, in my Time Clock Piece, I punched the clock every hour for the whole year. I wasn’t ‘producing’ anything..but in my philosophy, it was work. Was it worth it? I was discovered in the art world in 2009. Before that, only a few knew about me. I was in the underground.

KT: What have inspired you to create durational performance pieces, which were only made possible by your complete physical and mental commitment? You talked about these performances were like a journey inward for you to discover your inner tranquility and freedom. But you refused to relate it any spiritual activities or transcendence. Could you explain?

TH: I don’t like to talk about transcendence in my work because it means some spiritual activities. Again, this spirituality would make my work about ‘how’ to pass time. I was not training myself spiritually or mentally for some kind of elevation. You mentioned my work is ‘unwork,’ but unwork is also working. Anybody, if still alive, is working all the time to survive.

I also want to mention another aspect of wasting time. If you were to give one million dollars for someone doing nothing in a cage for a year, there would be a lot of people who want to do it. Their wasting time became purposeful. In my wasting time, there was no immediate gain. So my ‘unwork’ is a very tough ‘job’ that only a few are willing to take on. If someone else follows my suit and creates ‘wasting time’ work, then it means a whole different thing. If the concept becomes lucrative, then it doesn’t work anymore. It ‘worked’ for me because it was considered worthless.

KT: Tell us about your life after you became an American citizen. ‘Naturalized,’ in the official language of the law. What does this action of naturalization mean to you? Did it change your perception of art, survival, time and this country since you were no longer ‘living at the bottom of the society’ as an ‘illegal subject’?

TH: Does my documented or undocumented status influence my work? I wouldn’t say work is about ‘living at the bottom of the society’..more accurately, my art deals with time, life and being, and doesn’t respond the suffering of the lowest class politically or fight against something. That’s not my ideology. Critics can interpret my work, and that’s fine. But, here is what I think, when I say ‘art,’ it already denotes something high end, far from people living in the bottom. After I became ‘legal,’ it just meant I have to pay taxes and I can go back to Taiwan.

KT: It’s a luxury.

TH: Yes, it’s an expensive thing. When a person is hungry, he can’t think about those additional things other than his survival.

KT: But I feel that in your work, you combine these two contradictory things, and interrogate this paradox.

TH: Yes, when I say one thing, you can’t just follow it completely. You have to think the opposite direction to get the full picture. I tell you now that my work is not autobiographical nor political. But of course, you will find things extremely political in my art. However, my political viewpoint is leaning towards a more comprehensive sense of freedom. I don’t target specific and societal issues such as climate change or oppression of minorities and so on and so forth. I am political in the sense of freedom of thinking.

KT: Freedom of thinking in a philosophical sense?

TH: Yes, freedom of thinking belongs to everyone, and everyone can have that. Whether you’re a king in a palace or a prisoner in a cage, it doesn’t matter. That’s why I don’t think the change of my legal status in this country affects me that much. To me, being inside or outside the cage makes no difference. Likewise, being accepted into or excluded from the system shouldn’t matter much. Freedom is different. You have to pay the price to get it. We have to make a distinction here. But free thinking is free of cost. I dropped out high school to pursue freedom, and I paid a lot for it. Rebellion, Betrayal, crime, punishment, suffering, then freedom….it is a circle. Freedom is just a tiny reward after all the pain you’ve experienced throughout the process. And you have to keep fighting for it. It’s elusive.

Also, I didn’t do anything in the cage. If I could do other stuff like watching TV or reading a book, then it also wouldn’t work at all. People used to say I could have done my project in three weeks because they genuinely thought I was wasting time. And it worked precisely because of that.

KT: Does free thinking count as doing something, as ‘work’?

TH: Free thinking is the essence. Free thinking is like the heartbeat. You can’t break it down. You can’t control free thinking. Free thinking is limitless. You can’t stop thinking. Nobody can force anyone to ‘unthink.’ Heartbeat is work. Survival is work. Free thinking is work.

TEHCHING HSIEH

DOING TIME

TAIWAN EXHIBITION AT BIENNALE ARTE 2017

57th INTERNATIONAL ART EXHIBITION– VIVA ARTE VIVA

13 May – 26 November 2017

Palazzo delle Prigioni, Castello 4209, San Marco, Venice

Station: S. Zaccaria

Opening hours: 10am-6pm (closed Mondays)

Preview: 10am-8pm, 10-12 May 2017

Open on Monday 15 May

Outside Again is a short documentary on Tehching Hsieh’s performances, made by photographer Hugo Glendinning with writer and curator Adrian Heathfield, and shot in Taipei and New York. Watch online here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Kai-Chieh Tu.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.