Toronto Laboratory Theatre declares that its show, In Sundry Languages, “looks and feels like Toronto.” The collective creation devised by the cast features seven performers who not only speak English as a second, third, or fourth language but also speak at least one other language on stage, without translation. The show is a collection of scenes featuring bittersweet encounters between people navigating daily Toronto life, as well as stories about Toronto residents trying to put “others” into neat and easy to understand boxes. People who have seen versions of In Sundry Languages before may want to know that this iteration features 60% new material.

Arfina and Ahmed Moneka. Photo: Matthew Sarookanian

The piece is a collection of thematically connected scenes or units that are either narrative-driven, movement-based, or motivated by the need to explore a situation. In the first scene, an actor whose dominant language is Russian auditions for a role in a movie. The actor (Yury Ruzhyev) clearly won’t get the part of “Russian gangster” because the director does not think that the actor has a stereotypical mobster accent – although he does speak with accented English. My 12-year-old son was my companion, and he commented that not only must it depend on where you learned to speak English (Ireland, England, Canada …) but also that “Russia is a huge country: there must be so many different Russian accents.” Like most of the scenes, it is laugh-out-loud funny without being didactic and is critical of the way so-called multi cultural Canada addresses difference.

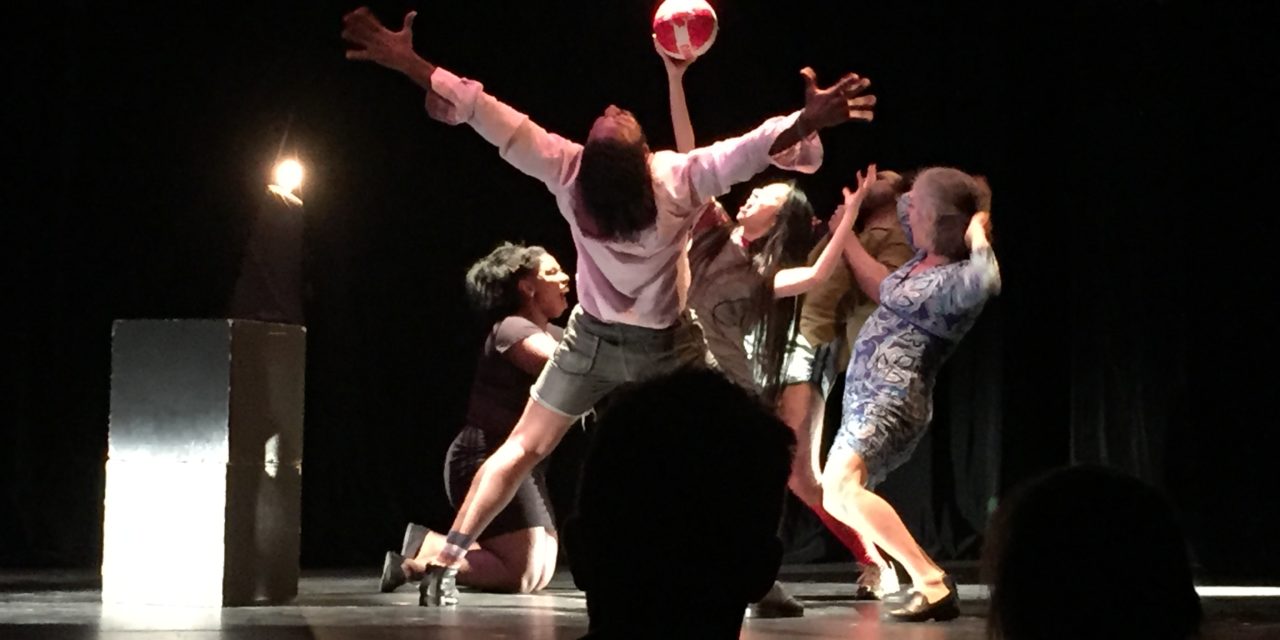

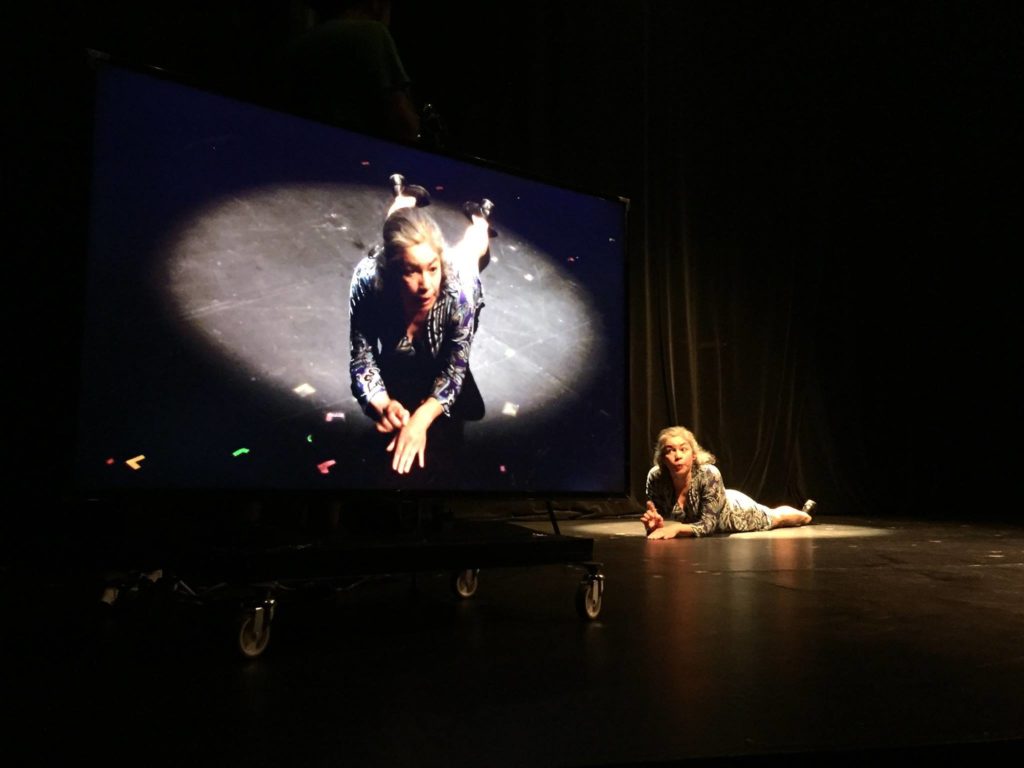

Director Art Babayants chose other scenes featuring spoken languages (Arabic, French, Mandarin, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish, and English), but the show as a whole also acknowledges culturally-specific body language, the language of music, the language of soccer, and the way language can shift via online communication like Skype. Babayants plays the piano throughout, underscoring the emotions and rhythms of each scene. An on-stage camera and screen often direct the audience’s gaze to a performer’s hands at one point, legs at another, eyes, and even a radical close up of a performer’s tongue. For me, the effect pointed out the significance of perspective, and also highlighted the fragmented way by which I listen— as I try to find clues to help me understand and communicate with others.

Lavinia Salinas. Photo: Matthew Sarookanian

The performers skillfully conveyed a wide range of emotions and often subtle narratives even when I could not understand their words. When I lost the details of a scene, I was riveted by precise body language accompanying the words. I felt like I was being told something that simply could not be explained as well in English, something that I still couldn’t quite grasp because I didn’t have those non-English language concepts to work with.

After the performance, conversations spilled out onto the sidewalk. I overheard a young woman saying that she thought the scene about trying to rent an apartment in which the receptionist used the word “blah” as a placeholder for unfamiliar English must have been how her parents felt when they first arrived in Canada. Another enthused about a scene in which people attempted to order coffee with sugar and milk. My son wanted to discuss a repeated vignette about two neighbors, one of whom asks the other, “Where are you from?”

My own favorite was the final piece: an encounter between the Russian actor we met in the first scene (Ruzhyev) and an audience member who fluently spoke another language before learning English. The actor selected a man who spoke Turkish, and both men sat together on the lip of the stage. Without speaking any English, they taught each other their names and then the words in Russian or Turkish for the sky, the stars, the heart, and even the moon. I realized that this was the first scene in which linguistic difference was not presented as a challenge or a problem but rather as a vehicle for joy. When the exchange shifted to English, the actor asked the audience member about flirting and love-making in another language. Gently supported and punctuated by Art Babayants’ piano, the conversation reveled in the beauty of linguistic and cultural difference. I was delighted that the audience member joined the cast for the curtain call.

When I was in Cape Town this summer I discovered that theatre audiences there are used to hearing multiple languages spoken on stage and that they expect to not understand everything. Subsequently, South African performers know that at least 1/3 of the audience may not understand them well at any given time, and so their performances require unique skills. In the case of In Sundry Languages the performance is about the multiple languages we heard, just as it is about stereotyping, racializing, identity, and the challenges of unfamiliar “newness.” This show is entertaining and thought-provoking. Even though the audience would have to work a little harder, next I would love to see a show, perhaps with some of the same actors, in which multiple languages are part of the storytelling but not the focus of story.

This post originally appeared on alt.theatre on July 13 2017. It has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Heather Fitzimmons-Frey.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.