On the stage covered with flour appears officer Bonet (Dmytro Surzhykov). Heavy and uneven white makeup creates an effect of death spots on the actor’s face. Behind him, there is a ballet of infernal reptile-ish revolutionaries, who leave no doubt that we are in Paris on the eve of the French Revolution. A skinny monk (Oleksiy Dorychevskiy) comes to visit Bonet, the guest’s baggy robe is covered with white powder. After all, everything here is covered with white powder, flour, dust. From time to time actors raise the dust (this is actually the reason why theater-goers were suggested to put on the protective set). The monk comes over to ask Bonet about the string of horrible murders that happened thirty years ago. Action on the stage is entirely a flashback, a tale of a crooked peevish old officer.

Project Aphrodisiac is a unique attempt for Ukrainian theater to perform a dramatic play in the space of circus. That is actually why it integrates several performing forms at the same time: it makes you remember of spine-chilling Freak Circus shows popular at the end of XIX century, fragments of du Soleil performances, and even mass street riots.

Except for the “wild” animal space of arena and necro-realistic aesthetics of the performance, one can clearly distinguish a dramatic tone, specific of this show: extremely vulgar, graceless, anti-sentimental and unkind to audience’s exquisite feelings. Pouring out the contents of pissing pot on someone, as well as obscene language, a choreographic metaphor of sexual act, travesty characters and extraction of the bloody candle from under the skirt of Madame Frashon, all these tricks and hints on the brink are routine practice for this play.

The story of Claude Ude, the founder of ideal aphrodisiac, starts the moment a Parisian commissioner saves a child that was abandoned by a local meat seller. “If God saved your life then I’ll give you a chance as well” – arrogantly and snobbishly states Bonet.

Although the life of the saved Claude Ude (Dmytro Usov) can hardly be called a “gift”. His childhood years will pass in Madame Frashon’s boarding-house (Oleksandr Yarema) – an old nymphomaniac with syphilis. Then the boy will be sold for fifteen livres to a brutal coffin maker Buke (Oleg Primogenov). After that, he’ll become a student of a pervert pharmacologist Anastacio Fumagalli (Oleksiy Vertynskiy). In fact, the entire first act is dedicated to this excessive, disgusting and at the same time aestheticized putridity of Paris. Each new scene depicts new places related to Claude Ude.The first stop is a market on a Paris square. On the stage we see a machine that looks like some demonic equipment of a magician, it is a box on wheels with a circular blade on it. It is here, that Claude’s slutty mother will be dismembered. Afterward, she will appear in Claude’s nightmares as a macabre dark queen, a figure in a crown made of knife blades, her face covered with black cloth.

The second stop is Madame Frashon, a lady always carrying a blister beetle in a small bag. She tries to force fourteen-year-old Claude to satisfy her sexual desire. Afterward, she will be found dead under “mysterious circumstances”: Bonet’s assistant, an exotic moor savage, kept on a leash by Bonet, extracts a big candle covered with blood from under her skirt.

The third stop is master Buke who was a regular “client” of virgin foster girls in Madame Frashon’s boarding-house. Do we need to say that he will die suddenly and mysteriously under unclear circumstances?

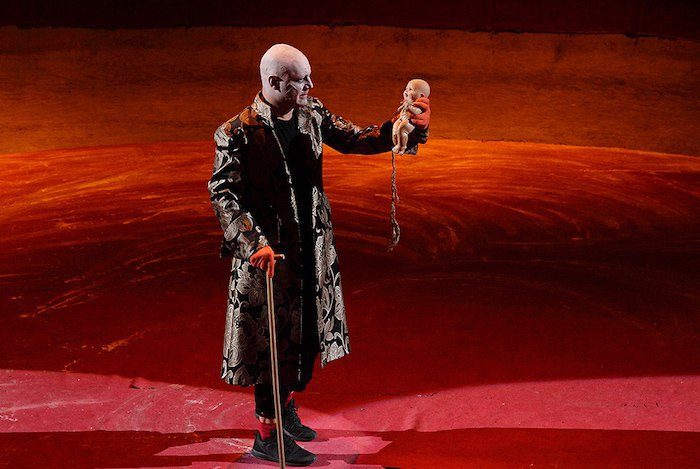

Aphrodisiac. Photo: Anna Hrabarska

And the fourth stop is a perverse pharmacologist Fumagalli, a man with an aura of grotesque nobility. Fumagalli has white curly hair and a totally inappropriate “karvel” on his head. Instead of selling pills and medical products he provides all Paris with aphrodisiacs. To his mind, the best monument for the city of Paris would be a huge metal phallus – this comic role was given to the Eiffel Tower mock-up. Everything corporal is depicted as dirty and disgusting. A body is no more than this if it’s not “fertilized” with the idea of fleshless God. According to Fumagalli, the smell of Paris is a total “smell of love,” in other words smell of sperm and body sweat.

However, Claude Ude is present in these stories only nominally. Compared to kaleidoscopic change of characters on the stage, the storyline (main idea) is progressing very slowly. It is worth mentioning that Victor Ponizov’s play (and this performance, accordingly) is based on the novel Perfume: The Story of a Murderer by Patrick Suskind. Epic literary form devotes significant attention to the elements that have no direct relation to the logic of protagonist’s actions. These elements befringe his biography or precede main events of the novel. On the contrary, dramatic form requires intense action and can’t stand accidental characters. Lost in a huge number of “additional” plot lines the authors leave the first act as a pure illustration, an extensive description of Claude’s life.

The second act reveals images of mutant characters: half-humans and half-beasts. Rich Earl who considers himself a happy owner of the “beastly magnetic vibe”, promotes the theory of “prenatal vivisection” that helped him gather his own collection of monsters, such as: a woman with a long beard, a cannibal, a fish woman with conjoined legs with black fish-oil leaking from her naked breast. In fact, the whole performance is a grotesque reflection of such involution. Love, being deprived of the fleshless component, transforms people into an intermediary link between animal and human. Only in the last part of performance Claude Ude finally appears as a real character with his own philosophy. He finds his “real love,” Aurora, a charming air gymnast, who is the only character able to take off from the arena and fly under the big top. In the second act, we are reminded of the performance’s object-matter – a soulless body: broken dummies that idly hang over the heads in the first act are transformed into a labyrinth for the characters, a huge pile of body parts where one can get lost.

The story of Claude Ude is the story of the unsuccessful birth of Messiah. He is obsessed with a challenging idea: he believes that God left this world long ago. However, it doesn’t mean that nobody can take his place. Claude passes himself off as a “superhuman” whose mission is to save everyone around, to purify the world with the help of a “unique recipe”. Of course, this magic recipe doesn’t help him. Moreover, at the end, infernal corps de ballet and beast-humans kill their new God. And a woman with black fish-oil leaking from her breast triumphantly holds a flag of French Revolution in her hands.

While watching all these peripeties of “Aphrodisiac” one can’t avoid an impression that the setting of this performance was moved here from some smaller stage, and the play itself is designed for a scope of small sentiments. The unexposed and raw space confuses people. As long as the circus is basically an amphitheater, almost the only scenography means left for dramatic theater, deprived of scenery, is the projection on the floor. Scattered symbolic objects that appear from the darkness, whether it’s an assembly line with dismembering box or clumsy metal safe, cannot hide its actual and vivid emptiness. Huge space of the circus remains unexplored, and vertical action appears only once, at the end, in the scene with air gymnast.

“Aphrodisiac” was meant to be a great “Montage of Attractions”, actors’ figures were meant to be bright noticeable silhouettes and the plot was supposed to become a philosophical parable in a figurative language of the circus. But unfortunately, it didn’t happen. One of the most interesting experiments of modern Ukrainian theatre evokes the feeling of embarrassment as if you accidentally caught a glimpse on a “naked” sketch. But at the same time, it makes us admire the endless potential of artistic forms.

This post originally appeared on Ukranian Theatre on May 25th, 2017 and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Olena Mygashko.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.