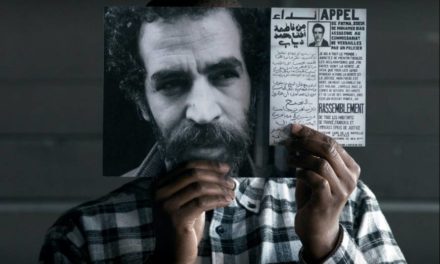

At their first encounter with director Alice Bogaerts’s and dramaturg Marleen Ilg’s stage adaptation of Howard Buten’s When I Was Five, I Killed Myself, spectators of the first part of Stadsnomaden2 are first put into disorientation. For those who already know the storyline of Buten’s novella on which the play is based, they might wonder how a lone, tantalizing, adult male body and a minimalist scenography would spatially play out the story of Burt, a troubled eight-year-old boy who, while being placed in a mental institution, is caught having sex with Jessica, his fellow child patient from the same ward.

BURT (When I Was Five, I Killed Myself)

As for those who come to the play without knowing the source narrative, Bogaerts’s and Ilg’s opening seems to invite them to a first-hand experience of how the main character “Burt” uniquely perceives the world around him. Actor Oscar Boy Willems, as Burt, has already started his intensive monologue before most of the audience would have a chance to reach their seats and properly sit down. The effect is a sheer disorientation. One has no idea what the character is talking about. It is difficult to make any connection between the words one is hearing, let alone connecting them with what one is seeing: a chunky male actor moving about in front of a hanging paper “backdrop” which runs downward and spreads over the entire performance floor, functioning also as the play’s “stage.

Although Burt’s speech gains coherence as the play goes on, the play’s specially designed opening scene where one is incapable of establishing any connections around him or her recalls the main character’s difficulty in properly embodying or fitting into the Symbolic Order, the system of social norms which a child internalizes when acquiring the language it speaks. This linguistic disorientation—highly reminiscent of the intellectually-impaired Benjamin’s speech which opens William Faulkner’s The Sound And The Fury [1] on which critics say Buten’s novella is based—suggests the main character’s challenge in relating to his environment and abiding by the social norms. Once the audience has gained their seats, we come to realize that these opening fragments are, in fact, repetitions of the same set of sentences, functioning like refrains or choruses in theatre, recurring throughout the solo performance. Willems’s perfectly timed delivery of these opening repetitions recounts the traumatic conflict between the authority of his father and Burt’s eligibility to access a space administered by the patriarch—a theme which resonates well with the spatial aspect of Theater Aan Zee’s trajectory, titled “Stadsnomaden.” This operation of the mind outside the Symbolic Order prepares us for the climactic moment of the play when Burt and Jessica, as two eight-year-olds, “perform” the sexual act against the approval of the rest of the world, however, through Willems’s emotionally charged narration.

The director and the dramaturg have well chosen the interior monologue as the play’s art form to represent Burt’s condition of severe autism. Instead of acting out different scenes pertaining to the source narrative, Willems’s solo performance, which is heavily grounded on the verbal, brings us inside Burt’s head while, at once, adroitly using his body, mainly, to exteriorise the main character’s feelings about things and people around him as well as his private thoughts and what he sees inside his head. For instance, at the end of the play, after Willems has verbally invoked, with admirably delicate sensuality, the climactic moment when the character of Burt has performed the adulteration of his and Jessica’s bodies—”when my downstairs meets her downstairs,” so goes Willems’s line—the solo actor moves his projectile muscular arms up to imitate the shape of a devilish winged creature as an exteriorization of what his mind is projecting: the haunting figure of Jessica’s dead father whom Burt thinks has come to avenge him for doing his daughter wrong.

Bogaerts’s and Ilg’s stage adaptation of the source narrative takes this expressionistic moment of hallucination as the play’s climactic moment which is then met by a brilliant scenography where Willems violently tears down the hanging paper “backdrop-cum-stage”—hovering above him and on which he has been walking—and wraps it around himself like a larvae buried in its cocoon. It is a scenography which visualizes Burt’s desperate need for protection from the trauma of guilt imposed by the Father figure (not only his own father but also Jessica’s) who is the guardian of the Symbolic Order. When the play ends with a sudden blackout and Willems has come out off this psychic shell, what is left on stage, revealed after the light is turned back on, is a crumpled tortured piece of paper sculpture—a stunning visualization of the character’s troubled state of mind. The scenographic design of the play’s “backdrop” and “stage”—whose functions are to delineate the theatrical space from that of the real world—to be literally as thin as a piece of paper reminds us of the vulnerable nature of the distinction between reality and hallucination the character of Burt experiences at the end of the play.

Throughout the play even until the end, we see, through Willems’s highly emotive performance, the unresolved tension between Burt and the Father figure which flow in and out of different male characters including Burt’s own father and the psychiatrist. Bogaerts’s and Ilg’s stage adaptation of Buten’s novella interestingly centers on the “guilt” experienced by this autistic character. It painfully sustains him on the verge between “madness” and “civilization.” This unresolved antithesis, together with Willems’s powerful performance, has thrusted the play forward in such a way that fully immerses and captivates the audience until the very last minute of the show. This tension between the “id” and the “superego” is brilliantly played out in the director’s and her team’s choice of the performance venue: a dark and heavy, most probably built in the belle époque, ominous school building. It is a space of social control which uncannily resonates with the others of its kind in the narrative surrounding the character of Burt: the patriarchal household, the school, and the psychiatric institution.

Guilt as the central element of this stage adaptation, furthermore, informs the ontology of this intensive monologue as the character’s “confession” to us audience. This, in turn, characterizes our spectatorship as “psychiatric”—an ontology imbued with instances of transference, especially that of the sexual desire which oozes out of Willems’s tantalizing body and his brutal yet highly sensual performance. The oozing out was literally concretized on stage by the character of Burt’s inability to contain his bodily fluids throughout the play—another brilliant visual transposition of the main character’s inability to contain/control his impulses and fit into the Symbolic Order. This is achieved through Willems’ adroit use of such minimalist props as the actor’s own saliva and bottled water which he uses to smear and soak his body and the performing space throughout the performance.

Blanks

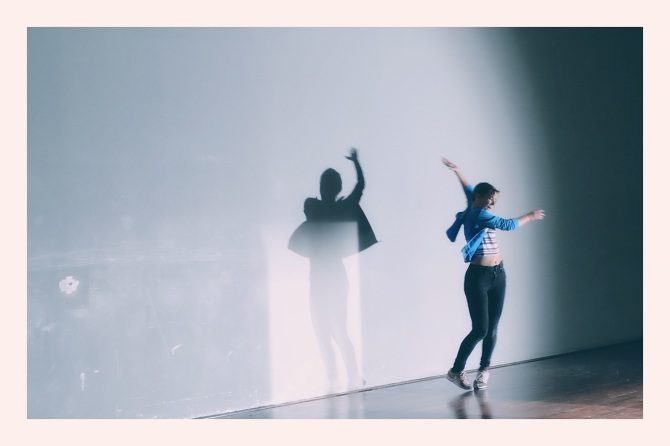

After a deep plunge into a boy’s interior world, the double bill continues with a much lighter, but by no means less intellectually stimulating, multi-media performance by Ingrid Berger Myhre. As the title suggests, Blanks invites us to a theatrical experience where any signification of the spectacle is emptied out or exaggerated. The effect is either there are no words at all or there are too many of them! By doing so, Myhre’s solo performance wittily unpacks the semantic process whereby the spectator acquires meaning of the spectacle in front of them. It allows us a performing and viewing space where “meaning” is not readily prepared to be given out to us spectators by the dramaturg and his or her script. The void of any textual description or the overwhelming presence of it is aptly mobilized to create “distance” between the spectators and what we see in front of us. By doing so, Myhre not only empties out any ideological framing usually attached in the act of seeing and frees us from any political affiliation we are usually made to subscribe to unknowingly. She also gives us back our ability to think critically about what is unfolding in front of us.

Credit: Jenny Berger Myhre

Despite its serious engagement with important thinking traditions in performance art, Blanks, crisp and electrifying, is never short of its capacity to engage and surprise the audience. Composed of different acts, the entire performance is, however, framed by the turning on, at the beginning of the performance, and turning off, at the end, of a portable cassette player placed on the ground of the performance space—an ontological marker separating the performance and the real world. The show begins with Myhre’s own airy dance which involves different gesturing of her hands in varied forms, however, without attaching any signification through words or texts to them. Freeing the audience from any description of the action being unfolded, her gestures, recognised as free-floating signifiers, however, ironically, tease the spectators’ habitual urge to guess and pin down what these hand gestures could actually mean—a clever way to engage and invite participation from the audience even though they still remain in their seats.

This habitual yearning for a (pre-)determined signification of a spectacle shared among the spectators is further teased in the act where textual instructions indicating when and where Myhre will reappear come up on the screen which forms the central backdrop of the performance: “She will reappear in approximately 6 minutes;” “When she does, she will be standing exactly in the place she rehearsed.” At this point, Myhre is wittily playing with the tradition of Brechtian Verfremdungseffekt (distancing effect) in theatre. She tells her audience in advance what is going to happen before it actually happens so that her audience becomes more distanced and critical of what is to be unfolded in front of them. Far from being didactic, this Brechtian use of text takes on a further comic effect when these textual instructions start to overflow the screen at a speed where no magical readers can ever catch up.

With the repeated emphases on the rehearsed nature of the theatrical performance—earlier appearing on the screen: “she will be standing exactly in the place she rehearsed”—Myhre, in another part of her performance, continues unpacking the naturalness of a theatrical experience, especially in terms of its spatiality and the performers’ knowledge of it. In this spatial engagement, she navigates the performance space with her eyes closed. Through this, she shows that through countless rehearsals where she has made an effective use of some parts of her body (hands and pace) to calculate the distance from one spot to another, she can reach the side curtains of the performance space with her eyes closed. This spatial measurement through the performer’s bodily indexicality is also seen in an act where, still with eyes closed, she brilliantly managed to make a balloon dog with the help of one of her hands used to measure the distance between one part of the sausage-like balloon to the other, before giving it a twist to form the dog figure.

Underlying Myhre’s practice is a good mix between the comic and the philosophical; fits of laughter and critical thinking about the politics of seeing—something contemporary performance needs to keep the field edgy, thought-provoking, yet highly capable of engaging the audience.

- Other elements of cross-reference include the motif of water, despite a different signification in Bogaerts’s play, and the synecdoche of the female sexual organ in form of Jessica’s swirling skirt, which is acted out on stage by Willems’s sensuously swaying his pajamas’ chords while in Faulkner’s this synecdoche comes in form of Caddy’s soiled drawer.

This article originally appeared in Etcetera on August 11, 2018, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Rathsaran Sireekan.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.