With Brexit and Northern Ireland constantly in the news, the timeliness of this play is not in question. First staged in London in the studio Upstairs space at this venue in April 2016, before the Referendum on the European Union, it is a co-production between Dublin’s Abbey Theatre and the Royal Court, and its return—this time to the main stage—feels disturbingly relevant. After all, it is about the psychology of Loyalism in Ulster at a time when, since the general election of 2017, the current Westminster government depends on the Democratic Unionist Party to maintain its majority in the House of Commons. So hardline Protestants and their uncompromising support of Brexit are daily in the news, and one of them is the central figure in this drama.

Watching David Ireland’s stunning drama, you can only hope that his picture of the Loyalist mindset is highly exaggerated. The story centers on Eric Miller, a Belfast Loyalist Protestant whose moody exterior, characterized by star actor Stephen Rea’s trademark hangdog look, conceals an even more moody interior. He believes that nowhere is safe and that his very being is under threat from the political realities of contemporary Ulster, in which compromise with the Republican Catholic community is essential for peace. But what brings him to a meeting with a therapist in this astringently funny play is a freakish feeling as dangerous as it is domestic. He thinks that his five-week-old granddaughter is Gerry Adams, the former Republican leader.

Yes, Eric is delusional. Paranoia is not a bad metaphor for the crisis in Loyalist identity, and Cyprus Avenue—a Belfast street celebrated by Van Morrison and the location of Eric’s home—begins with Eric being seen by a therapist, Bridget, as part of his “ongoing treatment.” Clearly, he has committed some crime that requires extensive therapy. It soon emerges that he really does need help. For a start, his hatred of “Fenians” (all Irish Catholics and Republicans) structures his whole world view. And for him, Fenians include any famous Irish person, and sundry others, including former President Barack Obama and Liza Minnelli. Oh, and he thinks they’ve infiltrated his own family.

Eric’s paranoia runs deep, but it is also very funny. The first half hour of this 100-minute show is full of nervous hilarity as the full extent of his craziness becomes apparent: his reason for supposing that his granddaughter is Gerry Adams has something to do with her having “Irish eyes,” smiling eyes, which contrast with his sense of Loyalism: “A Protestant’s eyes never smile unless it’s absolutely necessary.” But when he tests out his theory about the baby’s true identity by using a marker pen to draw a beard on this little mite, his wife Bernie and his daughter Julie are justifiably outraged.

Ireland’s play starts off in the therapy session, but Eric’s recollections soon people this room—designed by Lizzie Clachan as a neutral beige and white space—with his family members and his uncontrollable thoughts. In one brilliantly written long monologue he remembers a trip he once made to London, where he was appalled to find that people thought he was Irish, when in fact he’s always been taught to think of himself as British. Some other passage, as when he expresses his fears of a reunited island of Ireland, now sound quite prophetic. The drama takes a big leap into heightened absurdity when Slim, a film-loving and rather thoughtful member of the paramilitary Ulster Volunteer Force, arrives. A would-be terrorist in search of a victim, his appearance certainly raises the stakes.

It also makes the temperature soar off the scale, and this satirical comedy soon turns into a horrific piece of viciously violent in-yer-face theatre. The extremity of the play’s conclusion, partly inevitable, partly unexpected, has the audience gasping in astonishment and gulping in terror. Our laughter sticks in our dry throats. What started off as a joke becomes one of the saddest scenes in contemporary theatre. And what makes the incredible so credible is a phenomenal performance by the mesmerizing Stephen Rea, who never leaves the stage.

Rea conveys the emotional depth of Eric’s feelings, coming across not only as believable but also as occasionally charming. He is not merely a fanatic, but also a man who wants to argue and to persuade. Drunk on words, his craziness has its own impeccable logic. When he talks about Adams his voice drips with contempt. But Rea exudes menace as well as mania, and when he gets excited he paces up and down, his body tense and his floppy hands waving expressively in the air. Finally, when he loses control, there’s a real sense of danger on stage. It’s a compelling and utterly fearsome performance, a true haunting.

But as well as the sense of danger there is also a certain irony in watching Rea, who helped set up the Field Day Theatre Company in 1980 in Northern Ireland, a project which aimed to break down the barriers between different entrenched positions in the community, playing a Protestant Loyalist bigot so convincingly. Apparently, Rea was also one of the actors who were used by the BBC in 1988 when the Thatcher government banned members of the Republican Sinn Féin (as well as Loyalist militants) from being broadcast on television and radio. His job was to voice Gerry Adams’s words!

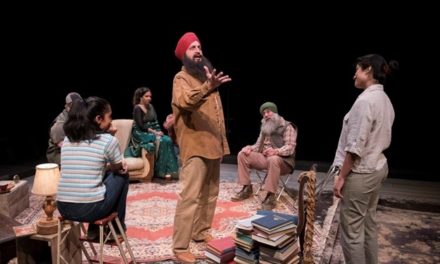

Cyprus Avenue is directed by Vicky Featherstone, who recreates her 2016 production and once again emphasizes the emotional distance between the characters by giving each of them a lot of space to move and talk in. If Bernie (Andrea Irvine), Julie (Amy Molloy), and therapist Bridget (Ronke Adékoluejo), are rather underwritten, they are still powerfully symbolic of Eric’s deep-seated fear of women. And of babies. The story is very much seen through Eric’s eyes, so much so that even Slim (Chris Corrigan) seems like a fantasy figure. Although I still think that some of the speeches are a bit overwritten, there is no doubt that the play is an extraordinary achievement, and certainly an exceptionally powerful piece of new writing. Its mixture of wild fantasy, satirical exaggeration and appalling distress will stay with you for ages after you’ve left the theatre.

Cyprus Avenue is at the Royal Court until March 23.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Aleks Sierz.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.