Whether you know it or not, we’re living in Brechtian times.

Central to the German playwright’s philosophy of theater-making was a Marxian horror — a real, urgent social distress over the failure of society — and an unshakeable accountability for its mending. The Brechtian aesthetic, present in all his work, is thus an identification of what needs to be changed — some alienated world — and an understanding of how theater might represent the changing of that world. He gives us a theory of our reality and a theory of art, theater as an autonomous understanding of that reality.

Perhaps this is why the Irondale Ensemble, nestled into the sleepy streets of Fort Greene, has engaged the playwright at just this moment. Last Friday, the ensemble opened its inventive adaptation of The Life of Galileo, the first in a three-play series called Brecht in Exile, which will present the playwright’s greatest work while writing in exile from Nazi Germany.

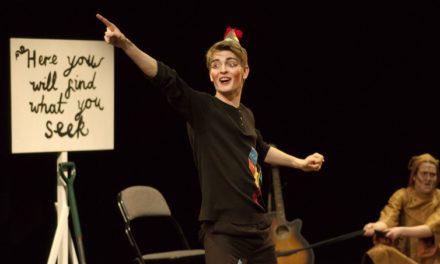

Its 42 characters played by an ensemble of only four brave actors, Irondale’s innovative and triumphant Galileo is Bertolt Brecht at his most excellent, cradled by an ensemble of dynamic and invested performers and pitched inevitably toward its audience with a playful, conscious eye toward its own didactic mission.

In 2006, Brecht’s Mother Courage and Her Children, presented in the dead heat of summer at the Delacorte Theater, was Tony Kushner and George C. Wolfe’s contemplation on the Iraq War. In that production, Brecht’s greatest anti-war play was revived to question what price we might pay for living off an endless and ambiguous conflict, the twisted, bloodied landscape of eastern Europe during the Thirty Years War presented not necessarily as history, as about some war-torn proletariat drunk on capitalism’s empty promises, but for whomever they might be today.

In a much smaller, intimate gesture, Irondale has endeavored down the same Brechtian path, inquiring what The Life of Galileo, Brecht’s dramatic telling of the scientist’s world-changing recantation, of that temporary victory of authority over science’s revolutionary potential, might mean in our contemporary imagination.

Set inside a modern workspace that could resemble any professor’s lab at City College — whiteboards and water coolers, coffee machines and outdated astronomic models (scenic design by Ken Rothchild) — it’s not hard to imagine what charged scientific endeavor, challenged by political authority in this country, director (and Irondale’s Artistic Director) Jim Niesen might be looking to reflect in Galileo. “Its taken nearly 400 years since Galileo’s discovery to get here, and we’re still far from finished,” writes dramaturg Jake Sellers in his production note. “The IPCC’s climate change report gives us 11.”

In Galileo’s recantation of his life’s work, in the temporary defeat of his Copernican challenge that the sun, not the earth, was the center of the universe, Brecht saw the original sin of all modern science. In that recantation—in the momentary victory of the Church and the yielding of science to it, in the vanquishing of the social and political possibility, that Marxist potential, of science in the market square — he saw the antecedent for the atomic bomb. In the same gesture, Irondale’s Galileo subtly posits if the human destruction of the earth’s climate, and the rejection of that science by political authority, may also follow from that original Galilean sin.

“Whether we feel it or not, the IPCC’s findings show the threat [of climate change] is very real. Much like the earth of Galileo’s discovery, we’ve got to get moving,” Sellers instructs the audience.

Yet, pulling the strings of some contemporary scientific morality out of Galileo is not easy — and that’s the way Brecht wanted it.

Written first in 1938, then re-written twice more over the course of his exile, first in America in 1947 and then again in 1955 in the wake of the Manhattan Project, Galileo is a historical drama, firmly bound by historical recreation. While Brecht may have seen in Galileo’s parable a usable past, the play is obsessively faithful to the events of Galileo’s life and confrontation with the Catholic Church (save a few details here and there). It’s a play bound by a post-modern preoccupation with fact and authenticity (a character of contemporary society Irondale may wish to characterize as waning), as well as the good, Elizabethan impulse to use the past to construct morals for the present.

As a result, what confronts those who engage Galileo is the need to parse what political lessons are contained in the history only, in the ink of Brecht’s pen or in the contemporary eye of its audience — and Irondale has met this challenge brilliantly.

Joey Collins, Chantelle Guido and Terry Greiss. Courtesy of The Irondale Ensemble.

At Niesen’s helm, the ensemble looks for these answers in a bare, nearly naked interpretation (using Mark Ravenhill’s pared-down translation, too) that is text and idea-focused.

George Bernard Shaw once joked that in lumping a few historical figures together in Saint Joan, he’d saved the theater manager “a salary and a suit of armor.” And choosing to have Galileo — even in Ravenhill’s simplified translation, still an exhaustive, tiresome play to consume — performed only by four actors is as daring, some might say foolhardy, as it is brilliant.

As members of the ensemble — Galileo played by Joey Collins, the rest by Terry Greiss, Michael David Gordon and Chantelle Guido — toss each scene to and fro, pushing some mammoth pendulum between them with ceaseless energy, it feels as if they are dramatizing both Brecht’s play and his thinking. Concerned less with character and more with a playful attentiveness to Brecht’s internal debate over authority and revolution, over what science is and ought to be, Irondale’s Galileo is as much a top-notch production of the play as it is a contemplation on the playwright himself, staged like a troupe of actors trading spirited performances, mulling over Brecht’s text.

In this, Irondale’s Galileo also succeeds in contemplating exile, in what the German playwright may have meditated apart from Hitler’s Germany.

Brecht saw Galileo as tragically human — original sin, after all, that most human of errors — as a dedicated humanist and an intrinsic idealist. What Galileo gave to the people of Italy, translating his works into the common dialect, was not just science, but skepticism and doubt. While his recantation may have cinched the initial flame of a people-driven scientific revolution, Galileo’s greatest mission, as Brecht saw it, hinged on an unshakeable faith in a populist, reason-driven victory over authority.

In the title role, Collins’ Galileo fulfills every idealist potential of Brecht’s valiantly flawed protagonist. Vulnerable and tortured, yet inspired and unshakably driven — a little mad, too — Collins’ portrayal is a first-rate, fully-embodied turn at the tragic hero. When the science and philosophy that fuel this play is laid to rest, what we ought to do with Galileo’s humanity — his recantation done purely out of fear, faced with certain death by the Inquisition’s torturers — is a question that haunts this play till its conclusion. Collins’ performance gives a brilliant answer.

Making her New York debut as a recent Carnegie Mellon graduate, Chantelle Guido, who portrays Galileo’s daughter Virginia and student Andrea, is a stand-out performer in this ensemble. Her virtuosity and emotional range — showcased brilliantly in Scene 14, where she must portray both characters at once — is a thrilling highlight in this play. And, in true Brechtian fashion, the original music composed to accompany the production by Sam Harmet, performed with Erica Mancini, is an unpredictable, suspenseful and autonomous force, mirroring the complexity and chaos of Galileo’s tragic descent into heresy.

As a German Jew in exile from Nazi Germany, absorbed by the revolutionary potential of Karl Marx’s social theory and drawn to the time of Galileo Galilei — a world that, met with modernity’s revolutionary and destructive potential, teetered on the verge of collapse, too — Brecht found Galileo’s scientific thesis, given to the people as an arbiter of skepticism and doubt, to be a powerful allegory for modern life. Today, as Irondale suggests, we may face a world not lacking in doubt, but one in which science is met with skepticism.

In no bombastic, self-important gesture, but in a studied, subtle and soaring take on Galileo, the ensemble asks, again, a simple question: will we recant?

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Michael Appler.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.