In 2005, Kankurang was inscribed by UNESCO as an intangible cultural heritage of humanity. The following year a project launched to safeguard the Kankurang and the Mandinka initiatory rites, drawing attention to this Senegambian tradition. In the next decade, The Gambia inaugurated the Kankurang Museum in Janjanbureh and revived some of the festivities that, up until the previous decade, had regularly taken place every few years. The 2019 Janjanbureh Kankurang Festival was the second time the festival was held, and the first time as a full-fledged weekend festival. The intention for the festival was to support masquerade tradition and cultural heritage, as well as to boost the economic development on McCarthy Island. The funding organization Youth Empowerment Project (YEP) describes how the festival “is geared towards the promotion and preservation of culture as well as creating employment opportunities for the inhabitants of the island town of Janjanbureh, particularly young people through Community-Based Tourism.” [i] It is in this predominantly Mandinka region and its surrounding sacred forests and sites (Tinyangsita) that initiatory rites took place and gave rise to the Kankurang.

—Fairy Masquerades at the Kankurang Festival. Photo by Aldith Gauci.

The 2019 Kankurang Festival was a much larger event than last year’s, with many more masquerades, and was well attended by both locals and foreigners who traveled to the island for the festival. According to oral narratives, the Kankurang’s origins date back to the Kaabu Empire (1537–1867). Besides the Kankurang, the festival celebrated Gambia’s cultural diversity and fifteen of the different ethnic groups’ masquerades: the Kankurangs of the Mandinka, the Kumpo and Essamaye of the Jola, the Zimba of the Wolof, the Fairy and Hunting of the Aku, and all their respective dance styles and music.

—Dembaningnyako Kankurang. Photo by Aldith Gauci.

The village of Janjanbureh was vibrant with energetic people playing music, warmly welcoming visitors and preparing for the three-day celebration. The arrival of so many tourists and Gambians from urban Banjul and other villages was indeed an event. On large grounds outside the newly established Kankurang Museum, and just up the road from the center of the village, a large crowd began to gather. As the masquerades arrived, all with their own dancers, whistles, beats and tempos, onlookers, families and supporters, the grounds became occupied by an organized chaos of simultaneous and very different masquerade performances.

—The crowd at Janjanbureh Kankurang Museum Grounds. Photo by Aldith Gauci.

Once the display began, different cultural groups took center stage and one at a time presented their music, dance, song, and masquerade. Onlookers cheered wildly for their relatives, danced and sang loudly, participating in their favorite masquerade performance. Often during the program spectators broke off from the crowd to join in the dance, offer money to the masquerade, or be a closer participant in the performance. The organizers separated performers from onlookers with rope, but it was of little use in controlling audience participation. The participatory style of performing was expected and somewhat instinctual for the spectators. The audience practiced very little self-control, as did the performers, who danced blissfully without taking the schedule under much consideration. Each of these dances would have been performed for a much longer duration and were adapted, shortened, and somewhat choreographed for the festival stage. [ii] With the different virtuosic elements, the captivating music, loud cheering, larger-than-life masquerades, steadfast dancing, and the continuous begging on the microphone from the organizers for performers to keep to schedule, the festival proceeded with an ecstatic program of events.

Kankurang

UNESCO’s inscription brought forth an effort to look into the Kankurang’s history and significance in the community. The effort to identify the different types of Kankurang and their individual idiosyncrasies also meant that the embodied and largely unwritten knowledges and oral histories of this practice began to be documented. Presented at the festival were the Fita Kankurang, Fara Kankurang (Ifangbondi), Wuri Kankurang, Jambajabally, Maamo, Senko, Jamba Kankurang, and Dembaningnyako. The Kankurang is attributed to the Mandinka people and served as a spiritual embodiment that guides, protects, educates, and disciplines the community. Whilst the Fita and Wuri Kankurang are more entertaining and appear often at different community ceremonies, the Senko and Jambajabally were memorable moments for the local community, who struggled to remember the last time they had met with these masquerades.

—Jamba Kankurang. Photo courtesy of NCAC.

The Fita and Wuri Kankurang is dressed in green mahogany leaves and dried, shredded bark of the camel foot trees found in the vicinity. He carries one or two machetes and is accompanied by fast drumming, whistles, dancing, and singing. The dance of the Fita and Wuri Kankurang is fast, rhythmic movements that make the leaves of the costume move, sway, and jostle. The feet dance energetically in small steps whilst the arms move in larger circles accompanying the movement. The body leans forward, and the center of balance is low, connected to the ground through the stamping bare feet. Sudden turns and sudden running away are not uncommon. Accompanying dancers also took turns to show off their dancing as part of the performance. As the Fita Kankurang dances, the floor becomes covered with leaves and branches falling off. The sand and dust from the ground begin to rise, and in the darkness of the night, these Kankurangs begin to resemble supernatural figures in the shape of leaves and trees. The Kankurang costume creates a larger-than-life figure that has more in common with a tree than with a human and refers back to the initial practice of celebrating and revering nature and the spiritual realm animating the masquerade.

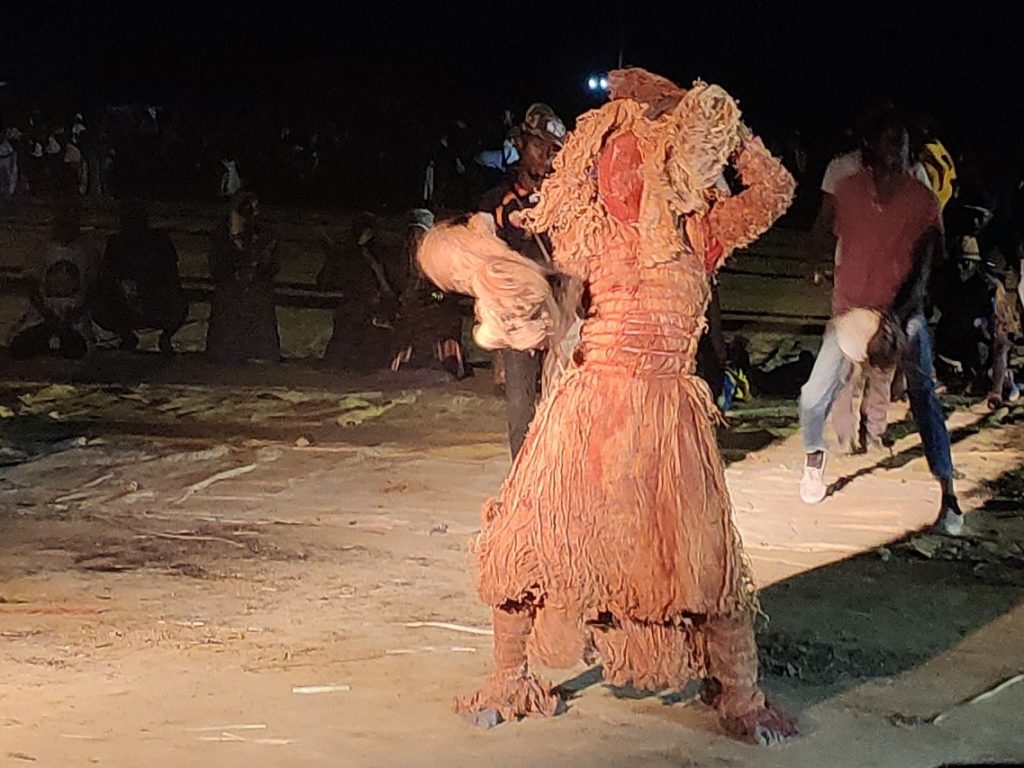

—Fara Kankurang. Photo by Aldith Gauci.

The Fara Kankurang was paraded in by a large entourage of men. He is completely covered in brown or red bark and carries a much less celebratory energy. He also carries two machetes that he clanks together. He is feared and respected by the community and demands discipline and obedience. His mystical reputation precedes his physical presence, and many tell of this Kankurang’s spiritual power, ability to fly, haunting scream, and legends of fatal incidents of punishment for civil disobedience. This Kankurang is strongly connected to initiatory rites and male circumcision. Initiates in the Mandinka community retreat into the sacred woods for what is known in The Gambia as “bush school.” This time allows initiates to be taught the ways of community living, including sex education, the unspoken laws in the community, respecting elders, medicinal and hunting techniques, and other “know-how and practices underpinning Manding cultural identity.” [iii] Despite the festival’s being simply a showcase for performances (and not a genuine occasion for Kankurang intervention), it was clear that the onlookers had a harder time establishing that difference and maintained their usual reverence for this masquerade.

—Fara Kankurang’s crooked standing position. Photo by Aldith Gauci.

Contrasting with the energetic accompaniment of dancers, musicians, and singers, the Fara Kankurang moved slowly and was characterized by the long fara headdress attached to the top of his head. The performer danced in relation to this extension, propelled it, threw it from one side to the other, or held it in pause in the crooked position as can be seen in the photo above.

Kumpo & Essamaye

—Kumpo whirling in fire. Photo by Aldith Gauci.

The Kumpo is a Jola masquerade made from shredded palm leaves of the rhun palm tree (the species endemic to all the areas occupied by the Jola) woven together to cover the entire body of the performer. Often, but not always, the Kumpo has a long stick attached to the top of his head. The performances of the Kumpo and Essamaye and their dance were amongst the most virtuosic of the program. For the most part, the Kumpo stood still, resembling an inanimate heap of hay while the dancing and music gather the crowd. As the performance proceeds, the “play gains momentum, a whirlwind comes and enters the outfit [of the Kumpo] and the Kumpo stands and starts dancing.” [iv] The moving image created by the leaves in motion affirms the spiritual function of the Kumpo that protects the community from witchcraft. Much mystery surrounds this practice, and little is known of the actual footwork that moves the Kumpo.

Accompanying the Kumpo was the Essamaye, a masquerade that usually animates a Jola wrestling match. The Essamaye at the festival lacked the typical white facial features and long mouth but followed the typical large neck and round eyes of the Essamaye. Also usual of this masquerade, he carried two sticks that he uses to dance and occasionally jump. His striking appearance is made from layers of jute sacks. As the Kumpo can only speak in spiritual languages, the Essamaye also serves to translate and help the Kumpo during the performance.

“The accompaniments are responsible for the orderly [behavior] of the audience during the Kumpo, to entertain when the Kumpo is away for his usual intervals, and to protect the Kumpo during the dance.” [v]

—Essamaye and Kumpo. Photo by Aldith Gauci.

Other masquerades

—Zimba and dancers in the background. Photo by Aldith Gauci.

The Zimba group was one of the favorites of the general public. Their modern flavor, explicit sexual references, acrobatic performance, and cross-dressing attracted the public’s attention. It was the most choreographed of the displays and resonated with the younger audience members. Zimba originates from the Wolof people in Northern Gambia and Senegal and is popular as tourist entertainment in hotels in urban Gambia. The Fairy and Hunting wore impressive, highly elaborate and striking outfits decorated with colorful ornaments and are more commonly found in the Banjul area around Christmas and Easter.

The festival achieved its purpose in showcasing local culture and tradition, supporting local enterprise and tourism. It celebrated the masquerades of some of the different ethnic groups in the area. Each masquerade spoke of its different purpose and history, territory and aesthetic. It reveals the masquerade’s strong ties with its environment (1) through its occurrence in order to protect its surroundings by intervening for harvest, rain, and maneuvering the community to take care of the territory; and (2) through its physical appearance. The materials the masquerade is made of refer back to the regional areas from which the masquerade originates: branches and leaves of the mahogany tree, the bark of the camel foot tree, animal skins, mud, leaves of the rhun palm tree, even the collection of urban items used for the Fairy masquerade. Because of the lack of natural resources, the Kankurang is today often made of synthetic vegetable sacks to replace the natural fabrics used. In the Kankurang Festival, tourism, employment, urbanization, tradition, and innovation are at a crossroads and major factors in the safeguarding of masquerade tradition. However, it is the significance and occurrence of the regional natural materials that complete the masquerade, making deforestation one of the biggest threats to this performance practice.

—Hunting Masquerade. Photo courtesy of the Youth Empowerment Project (YEP).

Aldith Gauci is a performance studies researcher interested in virtuosic bodies in world traditions and practices. She holds a MA in World Theatre from Aberystwyth University. Gauci, who was born in Malta, worked as Artistic Director for NGO Opening Doors (Malta), an arts organization for adults with learning disabilities. In Beijing (China), she created “Our Little Library,” inviting young children to explore storytelling and performative play. She is now living in The Gambia and pursuing her doctorate studies on Jola’s Kumpo performance.

Notes

[i] https://www.yep.gm/blog/kankurang-festival-20

[ii] The same pattern was observed by Neveu Kringelbach in her studies of dance in the Casamance and the occurrence of a neo-traditional genre of dance in its stage adaptation. She comments on how the duration is shortened, the dance is more choreographed and the “rhythms are accelerated to impress local audiences with the virtuosity of the performers” (Moving Shadows Of Casamance: Performance And Regionalism In Senegal, in Dancing Cultures: Globalisation, Tourism And Identity In The Anthropology Of Dance, edited by H. Neveu Kringelbach and J. Skinner, 143–60 [Oxford and New York: Berghahn Books, 2012], 154).

[iii] https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/kankurang-manding-initiatory-rite-00143

[iv] NCAC, interview with Bakary Kolley & Alias Coos, 2006.

[v] Ibid.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Aldith Gauci.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.