Hong Kong’s reputation as a safe city is well-deserved. It ranks frequently among the top 10 on The Economist’s Safe Cities Index, and reports of grievous incidences are few and far between. And yet Hong Kong is also known for its vast underworld of criminal gangs, a side of the city that has been immortalized in countless triad films and police dramas.

Triads, also known as “black societies” (hak1 se5 wui6 黑社會), trace their roots as far back to the 17th century, and their story has been depicted time and time again, to the point where any story about triads risks falling into a well-worn cliché. That’s why, for the 47th annual Hong Kong Arts Festival, playwright Loong Man-hong was tasked with bringing a fresh – and more human – perspective to the stage. The result is Gangsters of Hong Kong, which debuts next month at City Hall. After the Floating Family trilogy, this is the second time Loong has been commissioned to create a play, especially for the festival, building on his talent for turning topical social issues into a riveting theatre.

Actor Victor Pang, director/actor Lee Chun-chow, playwright Loong man-hong and Associate Director Tang Sai-cheong in the rehearsal for the play Gangsters Of Hong Kong. | Photographer: Viola Gaskell

“In the beginning, I thought, is there anything left to say?” Loong recalls. Over and over, Hong Kong movies like A Better Tomorrow, Once A Thief and Election have told and retold stories of the glitz, glamour, and gore of gang societies – deeply dramatic depictions with an undercurrent of violence running throughout.

Triads don’t just live in the movies. Loong acknowledges that their illicit undertakings did, in fact, shape the lives of a generation of people in postwar Hong Kong when poverty was rampant and police corruption deeply entrenched.

“Back then, there were a lot of night clubs and industries that needed a lot of security,” he says. “That helped gangsters make a living.”

Triads also extorted protection money from neighborhood businesses and smuggled drugs—particularly heroin—into Hong Kong. For most people, they were a scourge and little else.

But for those involved in triads, as well as those on the fringes of Hong Kong society, there has always remained another tale to tell. With few representations of triads in the theatre, as opposed to film, Loong saw an opportunity to portray a nuanced version.

“We don’t [often] see gangster characters, especially as ordinary people,” he says. “The Hong Kong Arts Festival wants to create different types of stories about regular Hongkongers.”

Set in Sham Shui Po’s Kiu Kiang Street in the 1970s, Gangsters Of Hong Kong is grounded in social history and the collective memories of an entire neighborhood. This was a community so tightly knit that the line between good and bad was often drawn into question. At the time, there were as many as 55,000 active triad members in Hong Kong, which then had a population of about 4.4 million. By contrast, there are fewer than 30,000 triad members today.

Loong man-hong. | Photographer: Viola Gaskell

The play’s narrative follows three middle-aged men: a reporter for a major newspaper, a long-serving policeman and a gang member. Their lives were once intertwined as youths, explains Loong, “and they all very much understood gangs because of where and how they grew up.”

While their lives led them down separate paths, they are brought together again by a graduate student from mainland China who is conducting research for her thesis.

Though not based on any specific events or characters from the past, the play’s main characters “represent a general portrait of people from that era,” says Loong. Drawing heavily on oral histories, he has sought to depict the realities of a moment of Hong Kong’s social history that has long been overlooked. To ensure he brought authenticity to the stage, Loong embarked on a year-long master’s programme in cultural studies, taking an academic approach to the study of gangs as a cultural phenomenon.

Gangsters Of Hong Kong explores the role of gangs on both community and culture, but it delves much deeper than that. Films have focused on romantic portrayals, but Loong looks to highlight grit rather than glamour – along with the interconnectedness of human relationships.

Sham Shui Po in the 1970s bore witness to Hong Kong’s textile boom, and with it, an explosion of cottage industries and an influx of people. Life was cramped and confined, with sprawling squatter housing and grinding poverty the day-to-day reality for many families. But with these cramped quarters came iron-clad communities that forged strong bonds.

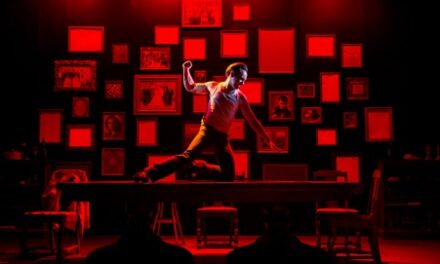

Victor (the reporter) with Lee Chun-chow (the former thug) rehearsing in the scene when they meet at Lee’s workplace, a recycling service depot. | Photographer: Viola Gaskell

Compared to film, theatre has less of a disconnect between the audience and the narrative unfolding on stage. Uncomfortable truths can be laid out for all to bear witness. In the case of Gangsters Of Hong Kong, when the characters are affronted by questions of their past, so too are the audience.

Rather than portraying a clear dichotomy—good versus evil—Loong used his research to add depth and dimension to each character and society as a whole. He credits a collaborative production process, which led the story to places he didn’t originally envisage.

“In the beginning, the script was kind of flat–two dimensional,” he says. “The director used his point of view and the actors use their understanding to execute [my] vision.”

Gangsters Of Hong Kong has already proven to be one of the Hong Kong Arts Festival’s fastest-selling productions. This begs the question: why the continued public interest if gangsters are no longer part of daily life for most Hongkongers? Loong’s answer is brief but poignant: because looking at the past can enable a better understanding of the present.

Asked whether he hopes the audiences leave with a particular notion in mind, Leung says he wants them to “think about what kind of society we live in.” In an increasingly fast-paced digital age, in a city that is changing at a particularly rapid pace, this proves to be a question more difficult to answer than most.

“I don’t necessarily think the concept of community has changed,” says Loong. “But it has changed in its form.” Whereas communities like the one he portrays in Gangsters Of Hong Kong forged a strong neighborhood identity, “today you might live in the same place for a long time, but not know the name of somebody that lives next door,” he says.

Communities haven’t disappeared, but their shapes, sizes, and the ties that bind them have been altered.

But no one is a passive witness to change. With community ties disappearing from the physical space, they are strengthening behind screens.

In the Facebook era, says Loong, “every community has its own group where people connect. Even if the news isn’t reporting something, residents capture it themselves and post their own commentaries.”

The black societies have adapted, too, turning to new illegal ventures as the industries that fueled them in the 1970s have disappeared.

“Gangs themselves, I think, will always exist, in every place and in every country,” says Loong. “As societies grow and economies change, there will always be illegal activities and the organizations that support them.”

And while we may continue to look back on the golden era of the gangster through a rose-tinted silver screen, we are left with the question: who are the gangsters and criminals in today’s day and age?

This article was originally written by Amanda Sheppard for Zolima CityMag on February 13, 2019, reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Zolima CityMag.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.