The EU Collective Plays project is arguably the most ambitious new play project in the history of theatre. Funded in 2015 at a staggering 1.8 million Euros, the largest arts funded project ever by the European Union Consortium, the project engages over 50 playwrights from 12 different countries in developing 8 new works for the stage. The charge given in executing collaborative plays with five or six authors is that they are polyvocal plays which maintain individual voices and dramaturgies, rather than attempting to construct a well-made play or realistic linear play.

The project was an initiative of Gian Maria Cervo, artistic director of the Italian Festival Quartieri dell’Arti and a playwright himself, who has invited me to collaborate as a general editor and curator. The theoretical grounds for this unique undertaking were given by my book New Playwriting Strategies, where I define the concept of hybrid play: a territory for the mixing or clashing of different genres, cultural or historical period styles, and techniques. The hybrid will often resort to various language strategies, found texts grafted into the play, strips of dialogue, mixing eastern and western dramaturgies, multiple levels of language, dialects, slang or different languages, and strange juxtaposition, like slapstick within a tragic or serious form, or characters interacting from different periods. Some hybrid plays may also be polyvocal, meaning that they resist the notion of the single authorial voice in favor of disparate voices and language strategies and the breaking down of hegemonies that privileges the single playwrights’ voice.

TThe playwrights involved in the EUCUP project, all with their natural proclivities and strengths, choose their angle on a particular subject, theme or personage. After an early workshop, for the writers diverge and the collective interactive work continues via Google docs, Dropbox, etc.. Before each meeting, the coordinating head writer determines the key structural components necessary so some general shape or structure is proffered. The head’s task is to facilitate the overall process, contribute as a writer, but also, functions dramaturgically to determine the most effective structural approach with significant attention to transitions. While each playwright may be designated specific scenes in the creation of the work, there may also be interactive sections with various contributors to a scene. Some of these arise out of conversations among the writing team.

The Nordic group is working on a play called Darkness. Its head writer and translator is Norwegian playwright and dramaturg Tale Naess, affiliated with the Oslo National Academy of the Arts (KHiO). Tale emphasizes that as a head writer her biggest task is “NOT to harmonize.” This is very important because it distinguishes these collective aims from more familiar collective formats, like television writing by committee; for example, where homogeneity is key, or separate parts are blended into the whole. Tale strives to not turn the script into a well-made play:

We want to “show” – or lay open the hybrid forms, the different ways of using language–maybe even different languages in the composition itself. I ask myself: How can this play “come together” while the differences continue to be present and vibrant. There is a force in the composition. I am looking for tensions and shifts, for the baroque and the theatrical. It is a challenge to think of this as real experimentation. To make something that can only happen with us, with this theme – at this particular time and space – in this historical momentum with this project, – and not think about: will the theatres like it, who would possibly want to play the roles, etc. I think we have a real chance to produce what you call a “hybrid” play. And a real chance to make this something from which we can learn.

In sum, with Darkness, like all of the plays in the EU Collective Plays the attempt is to celebrate the polyvocality of diverse languages, and language forms, that in essence, dialogize with each other in creating the hybrid play. Darkness mixes genres, and various speech forms, including the integration of Viking folk tales, Norse legends, speech genres (modes of speaking), and literary tropes. There are moves from dialogic interactions to more monologic transactions particularly in the opening and closing sections of the play. Characters emerge across the landscape: the loner, the hiker, the guy in the car to commit suicide, what children talk about when their parents are away. Each writer continues in their own language, some writing at the same time in English. Folk song forms, Nordic and Viking echoes, define the dialogic move. Ultimately, the translations into English present another set of challenges to get it right, while accepting the need for a broader understanding where carryovers from the native language to English are problematic, particularly, in tone.

Theme

For the Nordic team, the notion of Darkness is distinctly Scandinavian and illuminates its kaleidoscopic juxtapositions. The creation of Darkness explores how the seemingly harmonious Scandinavian society, where everything seems to be solved for you, makes the individual sometimes acutely aware of his or her inner demons. The Nordic group came up with the descriptor, “the enemy inside,” to describe this phenomenon. What happens if your happiness becomes solely your own responsibility? Having all your dreams fulfilled can lead to existential crises – even dreams of suicide.

The contributors are accomplished playwrights ranging across the Nordic countries, and also include, celebrated playwright, Albert Ostermeier, from Hamburg Germany. The team of writers is Sigbjørn Skåden, a Lappish or Sami writer based in Tromso, Norway; Kristin Eríksdóttir, an Icelandic author, poet, and performance artist; Gianluca Iumiento a notable Italian director actor and playwright based in Oslo for a number of years, and Tale Naess, the head writer from Norway. The Nordic group is affiliated with KHiO (the Oslo National Academy of the Arts), where the first meetings were held last December—the writers later met in February in Reykjavik, and May, in Germany. In writing their scenes, the playwrights begin in their respective languages and texts are translated into English along the way.

Contributors

For Kristin Eríksdóttir, the enemy within is directly related to the current socio-political and economic crises that have plagued the country until recently. First, is the theft of language, to maintain the Icelandic language from Anglification, a rigorous struggle to maintain its unique identity. (For example, Kristin assiduously writes in Icelandic even though she realizes it limits her opportunities as a playwright to reach a broader audience.) Efforts to go bilingual, even as the tourist industry has become the major economic force, have been thwarted, although the realities of a tiny populace (under 300, 000 native inhabitants) inundated with a 7 to 1 ratio of tourists (many from the UK and USA) mandates a widespread dissemination of English, in Reykjavik, where about two-thirds of the populace resides.

The darker enemy inside is the theft of believing in society that has stolen from you—the economy was devastated in a hedge fund scam by country leaders in 2008-9 that collapsed the three major national banks. Kristin’s image is that life in Iceland is a membrane, an almost impenetrable membrane keeping us outside of society. When I met with Kristin in Reykjavik in March 2017, she had just returned from Berlin, where she often works, and lamented that it is impossible to make a living simply working in her native country. This dichotomy of wanting to leave but feeling compelled to stay is evidenced in her creation of an equivocal character in Darkness who switches genders.

In translation from the Icelandic to English, Kristin’s own peculiar and strangely humorous way of using Icelandic when she speaks and when she writes creates something unique about the country – capturing this quality is essential to this translation. Not just in the way she constructs passages and sentences, but in the rhythm and the flow of her speech and writing. It has a whole quality in itself. A quality that not only induces style but gives added meaning. Her epigrammatic texts are first written in Icelandic, and then translated—and they provide the play’s prologue and conclusion.

Sigbjørn Skåden’s background is marked by the double bond of two cultures – one, Lapish, the other Norwegian. As an indigenous people, the Laps were for a period bereft of their Sami language due to several political reforms. Norwegian became the state language, religious rituals and practices were forbidden – the enemy within is the shame to be Lapish. The shame of your elders and their way of life, thinking and talking. This shame is an enemy inculcated in the Lapish psyche and society. A kind of darkness that has led to loss of identity, suicides among young boys and a strange kind of machismo among people that had a culture where the woman was as prominent as the man. Sigbjørn Skåden’s text was originally written in a dialect-based northern Norwegian with traits of the SNæss, for this occasion. She tried to preserve some of the original words like “marbakke” (deep sea) and “dauinghode” (dead man’s head – in North Norwegian dialect form), and names of places, settings, and the man mentioned, Kroken (that means croocked or bent like a hook). These descriptors create an extraordinary sense of “otherness” in the play even in its English translation—and essentialize its Nordic gestalt and world-view.

Gianluca Iumiento has written his text in English but tried to keep the rapidity and the rhythm of his original Italian language through the way he uses punctuation markers, spacers, and hesitant (commas, dashes, etc.) and the way he divides sentences and repeats words. The attempt has been to keep the feeling of his hybrid English in this reading, although it has been somewhat modified so that it is possible for audiences to understand it and relate to it. Iumiento as for many Italian theatre artists feels the “enemy” as the tension between the love of his Italian homeland and the necessity to move North to make a living. He created the loner character Julian, who in a harrowing scene prevaricates at the moment of decision on whether or not to commit suicide.

Tale Naess writes text both in Norwegian and English. In this version, she saves the word “engangsgrill” in Norwegian – mainly for the charm of it. It means a small dispensable barbeque. Tale finds that some of her texts are more facile to write in English while some come to her in Norwegian. While she worked in both languages – some words, especially the swear words function differently in each language. They might feel more casual and playful in English (the way they are intended) – but be darker and more sinister in Norwegian. Maybe even signaling that the children in the play are more aggressive than the average, or from a lower class.

Importantly, there is a text in the mix that is a result of notes written down during a conversation between the four writers, dialogizing between the various languages and English trying to relate to the theme in a contemporary setting. As the dramaturg, Tale took notes and dramatized this conversation. I think this again shows a fifth language level. Not a written language, but a kind of modified oral language, heightened into a dialogic move that, in some instances in this reading, interpolates sections by individual writers.

Setting

The setting is a peninsula, with a suburban shoreline connected to a large city with daily ferries, and then a darker interior with forests, lakes. The key to the landscape is the peninsula, surrounded by water, the vision of the play’s end is it breaking from the mainland and floating away in the North sea. In the end what happens when the enemy is not inside – but outside. In nature, when this peninsula – that is the world of the play – tears itself away from the mainland and floats off into the north sea. Darkness is scheduled for a completed draft October 1. It will be produced next summer at the Oslo International Festival of Acting. A successful preliminary reading of the current draft took place on June 15th, at Oxford University, in the Translation into Theatre and the Social Sciences Conference.

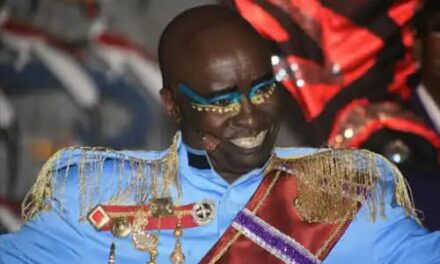

Workshop / workshow upon Family and Memory | Queen Helena polyvocal play, 2017, EU Collective Plays. Press photo

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Paul Castagno.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.