Though I never met my great-grandfather, I was told he was fond of saying “Lucky we come Hawaii.” It’s not the beautiful weather, access to a savory and delectable variety of foods, nor even our verdant majestic mountains and luxuriant sandy beaches which makes Hawaii truly special. People like to say New York is the melting pot—but I would beg to differ: New York is a salad bar (there are many different ethnicities, but they’re mostly segregated in one area—the Italian district, little India, Hispanic, Chinatown, and so forth.) Hawaii is truly a stew.

In Hawaii, unlike anywhere else in the world, there is no majority of one ethnicity; we all live and laugh together. This, for me, is one of the most critical aspects of our uniqueness—the reason we are so lucky and special: it is difficult to oppress the marginalized minority—near impossible to impose culturally tyranny—when there is no majority of one type of person.

Instead of public debates over immigration, a surplus of racially motivated violence, street fights, and name-calling, people in Hawaii—more often than not—just get along. Of course, there are exceptions—and, sadly racism does still exist, even in our island paradise. However, the amount of prejudiced, aggressive confrontations is significantly lower here. Our local culture is agglutinative: we use Hawaiian, Japanese, Chinese words, eat Portuguese Malasadas, snack on Korean seaweed and sometimes dine Italian or Thai. We are half Filipino and half Russian, half English and Vietnamese, half Japanese and half Swedish.

Significantly, since only 24% of the population is white, and there is no ethnic majority whatsoever, people talk openly about various cultures, are never forced to identify with a culture based on their own ethnicity, and see themselves as, simply, local or “from somewhere else.” Since a great deal of our cultural perspectives is bound by language, and since in Hawaii we speak English, we mostly identify as typical Americans. Of course, the main exception to this rule are people from another country who move to Hawaii (and therefore speak another language and may not solely identify with American values), or the second generation—raised in a bilingual household.

After being born and raised in such a culturally and ethnically diverse American state, I spent close to 8 years living on mainland America, and then the U.K. When I lived abroad, in places where I was a minority, I realized several things: for the first time ever, I began to identify as non-white, things which I would laugh about in Hawaii suddenly made me feel uncomfortable, and my attitude toward casting changed dramatically.

In Hawaii, joking about how “pake I am” is hilarious (pake is slang for Chinese and “being cheap.”) Telling my friend not to be portugee (or Portuguese, translation: “have a big mouth”) is a bonding experience: we joke, we nod, we laugh at our differences and similarities; stereotypes here are rarely threatening—they have been re-appropriated to the extent that they are powerless. Hawaii has a long and rich history of local cultural comedy—calling out stereotypes and laughing together at them (Rap Replinger, Frank Delima, etc.) Outside of Hawaii, very few jokes involving ethnic or cultural stereotypes were funny to me—the entire meaning of the joke (of course) changed with the context. I would still give my life for the right of any artist to say anything—no matter how offensive—but simultaneously, I began to see that politically-minded artists have a duty to impact society in positive ways.

Half Okinawan Cassidy Patmont plays haole Grace Fortescue and non-Japanese actor Chase Jusseaume plays David Takai in Massie/Kahahawai at Paliku Theatre, November 2017, Kaneohe, Hawaii. Photo by Orrin Nakanelua

In Hawaii, I was born and raised seeing myself as American, not an Asian minority. I was never excluded, oppressed in any way, nor made to feel inferior. The very notion that someone would view me as anything other than my individual personality was alien and incomprehensible. When I moved away, I began to feel more and more “Asian”—a perennial outsider, constantly being asked if I spoke Chinese (or Vietnamese or Korean—the question and implication were always the same, even if the specific country was different.) Since I have never asked any Caucasian American if they spoke Gaelic or Swedish, the accusation that I would speak any other language than English was both infuriating and bewildering. Suddenly, for the first time, I was no longer myself—I was an exotic minority.

I imagine being raised outside of Hawaii, as a minority, must be tragically difficult. Instead of feeling like an individual, you are constantly reminded of your ethnicity and supposed cultural heritage—which may or may not have anything to do with your actual personality. I imagine that faced with this kind of oppression, you either identify more with your ethnic background—embracing it as a shield, or less—disavowing it. This is speculation though since I was raised in a place without any ethnic majority.

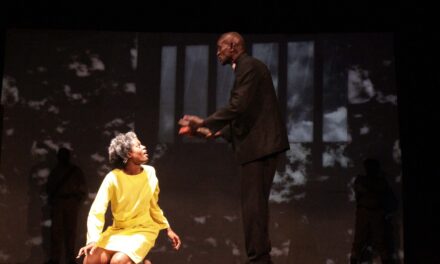

Away from Hawaii, yet another strange transformation was my view on casting. In Hawaii, I am adamant: the most talented person is who the role should go to. Outside of Hawaii and outside of educational circumstances (college, collaborative efforts), I would cringe to see a white person playing a non-white character—no matter how talented. In Hawaii, a British queen could be played by a Malaysian woman, a Japanese played by a Chinese, a Filipino played by a Samoan, a Korean by a Caucasian. The only time we adhere to ethnic recommendations in casting is when its integral to the entire theme of the play (and the play is not being deconstructed.) For example, a non-Post-Modern staging of Othello in Hawaii will almost invariably use a black actor for Othello, and white actors for most of the rest of the cast. Outside of these specific circumstances—where ethnicity is fundamental to the theme and meaning of the entire production—anything goes with casting. I would not flinch to use a white actor in a Japanese role, in Hawaii, if the white actor was somehow better for the role—more talented, easier to work with, more dedicated. I recently directed Massie/Kahahawai at Paliku Theatre and used a half Okinawan half-white actor for the Caucasian female role, a black actor in a white role, and a white actor in a Japanese role. No one batted an eyelid. Indeed, the casting underscored the theme of the play: locals of all ethnicities banding together to fight injustice.

Likeke Nakachi-Isaacs plays Joseph Kahahawai and mixed race Jessica Jusseaume plays haole character Thalia Massie in Massie/Kahahawai at Paliku Theatre, November 2017, Kaneohe, Hawaii. Photo by Orrin Nakanelua

Outside of Hawaii, in most places, choices such as these are an impossibility. Using a white actor in a non-white role, when there are so few roles for actors of color, in the face of the horrible history of white-washing, is outrageously irresponsible.

The differences between the state of Hawaii and the rest of America are extreme and copious. Here, in proverbial paradise, we are gifted in the singularity of our laughter: we can laugh at ourselves and our differences. And in this laughter, there is no overt or latent threat (the threat of the majority isolating or menacing the minority). We can speak openly about cultural differences without peril. We identify with whatever culture we fancy (currently I think I’m French.) And we can almost always cast anyone we damn choose.

Having lived abroad, I see now how our environment shapes us, how the landscape etches indelible marks on our cultural identities. Warm, embracing, gentle surroundings nourished the welcoming and loving culture of the Hawaiian people. A massive influx of immigrants to work the plantations in the 19th century led to an astoundingly diverse population—accepted by the compassionate native civilization. (Missionaries of the early 19th century constantly recorded their astonishment at seeing Hawaiians share everything they had, with complete selflessness: “today I saw a boy give the last of his tobacco without hesitation to his friends.”) Indeed, in traditional Hawaiian culture, the notion of ownership did not exist. Everyone cared for the land; a man could not own a woman in marriage. These remarkably admirable traditional values were ultimately used against the Hawaiians, who suffered inexpressibly from foreign disease and loss of their lands. When the Great Mahele was instituted, few Hawaiians could comprehend they had to legally claim the land they’d lived on for thousands of years.

Here in Hawaii, we have the incomparable luxury of laughing at each other and ourselves, color-blind casting based solely on talent and dedication, and never feeling like an outsider or exotic other. Here in Hawaii, we all owe native Hawaiians a massive debt. Their aloha has unquestionably allowed us to coexist in enduring peace, and produced an extraordinary, mostly egalitarian construct of society; from my view, the vision of the world they imbued us with is the very fabric of dreams.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Taurie Kinoshita.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.