On a cool July day, in between heat waves, five people gather in a virtual meeting to talk about restorative ecology, magic and art. ‘Can you hear me?’ Fumbling with microphones ensues, one pair of earphones is swapped for another pair, and then all is set for a deep conversation on listening to the human, non-human and more-than-human. In this group interview, four artists with non-Western practices talk to Lena Vercauteren about what it means to work on restorative practices, spirituality and magic in a Western, hyper-individual world.

The four artists invited for this conversation each work with slightly different art forms, ranging from aesthetic objects and installations to video, performance, and various hybrid forms. Gabriela Carneiro da Cunha has researched the ecological catastrophes happening in rivers and turned these spiritual river testimonies into performances. Maria Lucia Cruz Correia has done related research with the Natural Contract Lab, working on climate justice in regard to various rivers like the Zenne in Brussels. Isabel Burr Raty has worked as a filmmaker and performance artist with a strong focus on developing the body and its (sexual) energy. Dodi Espinosa, the fourth and final guest, creates artistic objects, like ceramics, and facilitates meditation workshops with ritualistic and shamanistic elements.

In March, all four of them participated in the Women and Children First festival at VIERNULVIER in Ghent, centering around magic, rituals and contemporary witchcraft. The artistic work of each of these four artists has strong ties with spirituality and magic as a means of restoring our connection with nature, the collective and ourselves.

Isabel, when did restorative and ecological practices first come into your life? Was it a single moment or a gradual process that inspired you to work on these themes?

Isabel Burr Raty: Well, I am half Chilean, half Belgian. I was living in Chile for an important early phase of my artistic practice. I ended up living on Easter Island. As a filmmaker, I was documenting the struggles of the Rapa Nui people, which is a local indigenous community that is fighting against the Chilean government to obtain their autonomy. I was making a film about this struggle, following the leader of the community. The community wants to regain ownership of their home, so that they can restore the space. It is not just a political fight, but also a philosophical and spiritual one. Because they understand their environment to be an extension of their bodies. What is done to their land is done to their body.

My research on their understanding of the body started crossing over into my own hybrid practice of performance and installation. We started working on bodies that make restoration. We thought about what is considered waste and what is considered contamination and how we can maybe reclaim bodies that have been infected by external concepts, like processes of colonisation. I started focusing more on the materials that are coming out of the human body, that are considered waste. By working with this waste, how can we restore the human within a more-than-human landscape? And that involves the question of ecology, for sure. How to reclaim the ecology of the body within a bigger ecological context, where there is a catastrophe happening, on many levels. I would say that moment is what got me into this theme.

Is this the same for the rest of you? Was there really a moment that started this desire to work on these themes?

Maria Lucia Cruz Correia: Well, I would not say that it’s a clear moment or a desire. I think it’s more like a call or like a mission that you feel that you belong to. Like Isabel, I also grew up in a village, by the sea in Portugal, close to a natural park. So, my roots are very earth-based, in a very crystal-clear environment, which also has had moments of disruption. In my artistic practice, I have been researching and working a lot on the impact of environmental crimes in different territories and, more recently, in bodies of water, like lakes and rivers. A common thing that I saw in all these cases is the impact on the species, on the more-than-human, but also on the people.

When we think of environmental crimes, we sometimes forget the impact on the human level. About the activists that are fighting for the protection of those places and very often end up with exhaustion and depression because of this fight. I started thinking a lot about this environmental collective trauma and this grief that we constantly are living in. The loss of the landscapes that we constantly see disappearing. We have no place to put this loss and these emotions that come with the grief of things that are constantly disappearing.

In that sense, I feel that my practice revolves around how we can foster other methods of care: self-care, collective care and ecological care. This also means thinking about new forms of democracy for care, or the politics of care. Instead of restoration, I would maybe call this idea reciprocity and reciprocal care, in which we take care of the landscape and the landscape takes care of us. We are constantly fighting for a territory, but then we forget to lie down and feel this territory, to consider how this can be a cycle of reciprocity. We are the landscape, we are the river, we are nature. It’s embedded in us.

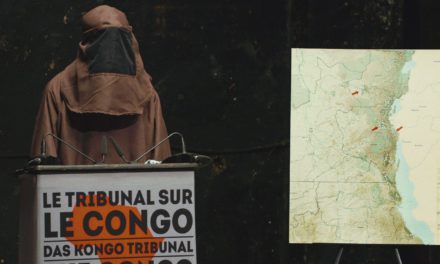

Maria Lucia Cruz Correia @ Turn #2 Lab 3 – Dream City

Gabriela Carneiro da Cunha: The work that I do is about listening to the testimony of rivers that have suffered a catastrophe, from the river’s perspective. During an earlier project on guerrilha women, I worked with people on the Araguaia river. With these people, I learned that it was possible to listen to the testimony of the river itself. Suddenly the research project became about a language, about how to listen to a being that I don’t share a language with. About who can testify, when humans become the catastrophe. It became an artistic response to what we call the Anthropocene.

When the project became about listening to the testimonies of rivers, it became about a lot of things. Because as Isabel said, these people understand themselves as rivers. Listening to a river is also listening to the spirits is also listening to the people is also listening to the animals is also listening to the wind is also listening to the rain. It’s listening to lots and lots of beings, who share and live — not always in a peaceful way — this whole cosmology. So that’s where I was. In the territory, together with the people, together with the nonhumans, together with the dreams, together with everything, together with breathing, with all these practices. And in the middle of it, this restorative ecology arrived. But it didn’t begin with this.

Dodi Espinosa: Like in nearly every case, I think where we come from has great importance. I come from Mexico. I grew up in Teotihuacan, which is an archaeological site 40 minutes from Mexico City. Throughout my childhood I assisted in Pre-Hispanic dances and practices. I went to all kinds of ceremonies and I had a spiritual mentor. So I grew up in a context where art actually has no separation from the spirit. Like everyone here is saying, there is no separation between humans, the environment, animals. Everything is one single entity. In my case the evolution was kind of different. At one point, after my early immersion in Pre-Hispanic cultures, I got very interested in Eastern philosophy. I started to travel a lot through Southeast Asia and got very interested in Buddhism and Hinduism. That’s how I got into the practices of Tantra, Yoga and meditation. At a certain point, the practice of meditation, specifically Zen meditation, became the core of my own life and daily practice.

A big part of my practice as an artist right now revolves around facilitating workshops or guided meditations in art institutions. Alongside that, I also try to bring awareness on certain urgent matters, because spirituality has become a matter of capital. You know, there are many modern gurus or shamans making a lot of money peddling misconceptions and that is very dangerous. I always try to remind people, based on what I learned as a kid and what I’m studying right now, that there is no separation between humans, animals and environment. In Hinduism and Buddhism there is the concept of non-duality, which means no separation from the rest. It’s a feeling of oneness that you can achieve through meditation. In the last few years I have been very active as an animal rights activist too. Even though I really enjoyed it, and I thought it was very important, I also realised that that’s more a kind of shock therapy. And sometimes the true change, I think, has to happen more from the inside, from conscious inner work. Once this happens everything follows.

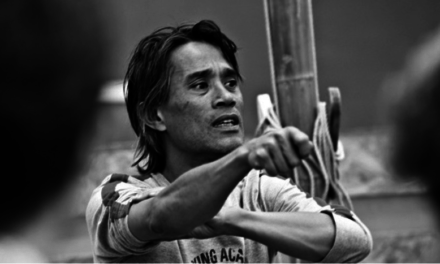

The Power Plant Village Research 2, Isabel Burr Raty.

I think it’s interesting what you say about there not having been a separation between art and the spirits in your childhood, Dodi. I wonder how this connection between art, magic and spirituality is in other artistic practices.

G.C.C.: I cannot speak in a general way, but I know that the people that I work with and the territory that I work with, they cannot talk to me about the catastrophes that are happening to them and to the rivers without also telling me about the spirits of the water. When I am listening to the testimony of the river and when I’m listening to the testimony of the people who live near the river, they tell me about the spirits of the water, the mother of the river. And how they will work together to fight these specific conflicts and this specific situation.

There is this relationship between spirituality, life, political conflicts, economic interests, colonial issues and historical issues. When I work with all this and when I make what I do — because I am not a shaman, I am an artist — what I feel is that I can touch and exchange with all this. One of the questions I work with is: what can art become when it encounters Shamanism? Because Shamans operate in the ability of seeing, in the ability of listening and the ability of dreaming. I feel that art also operates in our ability of seeing, of listening and of dreaming.

It’s also very important to understand that a river is no one’s subject. A river is a language. So, to work with the river, you have to learn and listen to this language — and language is also the substance of art. It is in this sense that all these things relate to me.

I.B.R.: I think the understanding of spirituality or of the invisible, of the forces of the space that we inhabit and what we can do with them, are also related to this idea of healing. For me this raises the question about who has the power of healing and what healing is. I’m interested in democratic ways of healing. That is to say what it means to have somebody who has authority, who will guide you through a healing process, versus what it means to make healing collective, where all the tools are put out there and shared. How can we avoid granting the power to one person as a guide? Because completely relying on a doctor or a shaman creates dependency and possible manipulation.

How can I be a direct channel? How can you be a direct channel? How can we all be direct channels? In my practice I think about how we can maybe live within a more integrative metaphysics. How the physical, even on an atomic level, and the invisible are super-entangled. When we speak about consciousness, it’s very easy to stay in the binary of body and mind. To think about where the consciousness is in the body. While actually, that consciousness exists because there is a body.

That’s where I’m doing my research now, in the biochemical internal reactions that have the power to awaken certain potencies or to make certain potencies dormant. In my current project, called Power Plant Village, I’m trying to create a village where we awaken dormant hallucinogenic neurotransmitters for transdimensional travels, via conversion of sexual energy into power. I was trained as a sexual Kung Fu practitioner, in the Taoist tradition. There I started seeing the interconnections between the neurological system, the endocrine system and the microbiota system. You realise that it’s kind of like this whole internal machine. So, when I think about how to make healing available for everyone, it would be more a matter of understanding the bioelectrical circuits of the body and of the landscape. That doesn’t happen through one person.

Altamira, Gabriela Carneiro da Cunha. Photo by Nereu JR.

L.M.C.C. Yeah, it’s also this idea of magical activism. If you think of Earth-based magic, it all comes from nature and we all get its messages. We can learn from the trees, how they dialogue. We can learn from the plants, how they transmit nutrients to each other. We can learn from the water, how the water flows through a territory without boundaries. And if we listen to our inner landscape, we can find the resources to transform and to generate new narratives for a future. I also think art has the power of imagination that goes beyond the understanding of a lawyer or a scientist. We can learn from the data, we can learn from the history, from the archives. But through art we are capable of reimagining and interweaving and weaving different knowledges and wisdoms.

I’ll tell you a story about magical activism. With my projects on rivers, I work with lawyers and restorative justice practitioners and we work with different groups. And of course, there’s a lot of resistance about bringing more holistic tools into the process. But we have this vessel that we call ‘River Vessel’, where we collect water. One of the rivers we worked with was the Rhône. We worked with the employers of the Council of Geneva, who worked on the water legislation, or were engineers, all kinds of people. As a statement, we didn’t ask what their profession was or what they did in their job. We asked: ‘What is your relationship to water?’ So then I knew, for example, that a certain man went to the riverbank at lunchtime, but I didn’t know that he was someone who was passing legislation for the protection of the river. By being in the river and by bringing these people together, it awoke some kind of relationship. We worked with them with the same ‘River Vessel’ for all the sessions. They brought it inside their offices. Between two sessions, I asked them if there was any story they wanted to tell that happened while this vessel was present with them. And they told me that that day the finance department got flooded!

I think magic is about listening to the elements around us. When you open a path for these elements, like bringing the water of the river inside a super important government building, maybe the river will do its work by itself. So, I think that magic is the power of our will and the will of our kin and our companions and allies that are part of the ecosystem.

We’ve talked about how the Western world has a different way of looking at and working with spirituality. But there is also a different way of looking at art. Do you feel like it’s hard to bring restorative art practices in the Western art scene?

D.E.: I think so, yeah. I mean, the art industry is controlled by the market and by what the collectors want to have in their house. I like to make objects, but sometimes I struggle because galleries often consider that I may not be commercial enough, that’s also why my practice is expanding and I’m working more and more in hybrid projects in institutions. The more I meditate the more I try to contribute to the community. I agree with what Isabel has said, in the sense that we are in a moment where the responsibility is not just on one person, but on the collective. That’s also why I give these workshops on meditation, which I like to call medicine instead of magic. It’s like the medicine of living deliberately.

I like the practice of meditation because it’s very democratic. You just need to sit consciously and that’s it. You don’t need to take a flight. You don’t need to take this or take that. You don’t need to buy anything. It’s just about sitting, the exercise of concentration by bringing attention to posture and breathing.

I do think karma brought me to Europe. Because we all know the impact of the West in countries like Brazil, Mexico, in countries in Africa, Southeast Asia, etc. It’s horrible what is happening there. Where my grandmother lives, there is no water anymore, there are no rivers. And I think it’s actually very important to be active in this part of the world, in Europe. We have to bring awareness about the consequences of our habits here and now. I think that’s also a kind of restorative practice, to bring this kind of awareness in us, because we have the privilege of living here.

Mini Zen, Dodi Espinoza.

G.C.C.: Surprisingly, I actually have a piece, Altamira 2042. The piece is about a hydroelectric dam on the Xingu River, and at the very end of the work, I call seven women so we can all break a rock in the centre of the stage. While we are breaking this rock, the audience is also part of this ritual. Everybody is working together. Because I understood that no one is breaking a hydroelectric dam alone. We need a lot of people and non-people and spirits together. The purpose of this performance is to engage everyone. On top of this, I also facilitate an encounter between water. For the performance I use water and I always bring the water from the Xingu and the water from the river of the city where I am performing. So there are a lot of little things that are done that you can call magic or you can call it the preparation for the performance or you can call it art.

Dodi likes to call it medicine. I like to call it theatre, but it’s theatre that is also medicine and that is also a ritual. That is also activism. That is also shamanic work. That is also art. It can be all that, but it depends on the engagement of the public. It depends on the day. It depends on a lot of things. That is something that I have learned in the Xingu. There’s this sentence that we write in the performance which is: ‘to be and to be and to be and to be’. It’s not ‘to be or not to be’. Because there is no possibility of ‘not being’ when you are in the Amazon. Everything is.

There is a Yanomami shaman that I work with, called David Kopenawa. In his book The Falling Sky, he says that white people sleep a lot, but they can only dream with themselves. They have lost their ability to dream far. To dream with others that are not themselves. I think that’s also something art can do. It can open and amplify the ability to dream and to listen to others that are different from us. It can be other cultures, but it can also be other bodies, other beings, non-humans. That is what art can do.

I.B.R.: I agree. I think I’m more of a conceptual artist. I do have a background as an actress, actually, and as a theatre maker, but I ran away from it after ten years of working in that sphere. I got tired of representation. I’m now working on embodied practices. I invite the public to live through things, through experiences of transformation and transportation. It is very hybrid. I work knowing it’s art, but also knowing that there’s a certain urgency. I believe that what I do will have a direct impact on the way people live. So every work I’ve done has its own energetic weight that somehow attracts the right people. I’ve been very fortunate in that sense. In Chile, it’s much more difficult to live doing your hybrid stuff.

Now, fortunately, I’m not object-based, so it’s more about a narrative. Meaning is created via the stories that I tell. And because there’s an urgency, I think I not only have the chance of being programmed, but of having a public that understands this urgency. Maybe it has to do with this shift of consciousness that humanity is experiencing. I mean, I just saw a photo of I don’t know how many people sitting on a yoga mat in Times Square in New York, you know? I know that the economy has appropriated a lot of spiritual practices, that’s for sure, there is a lot of commodification. But I think there is a general need for understanding the human experience differently.

This article appeared on Etcetera on September 15, 2023, and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, please click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Lena Vercauteren.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.