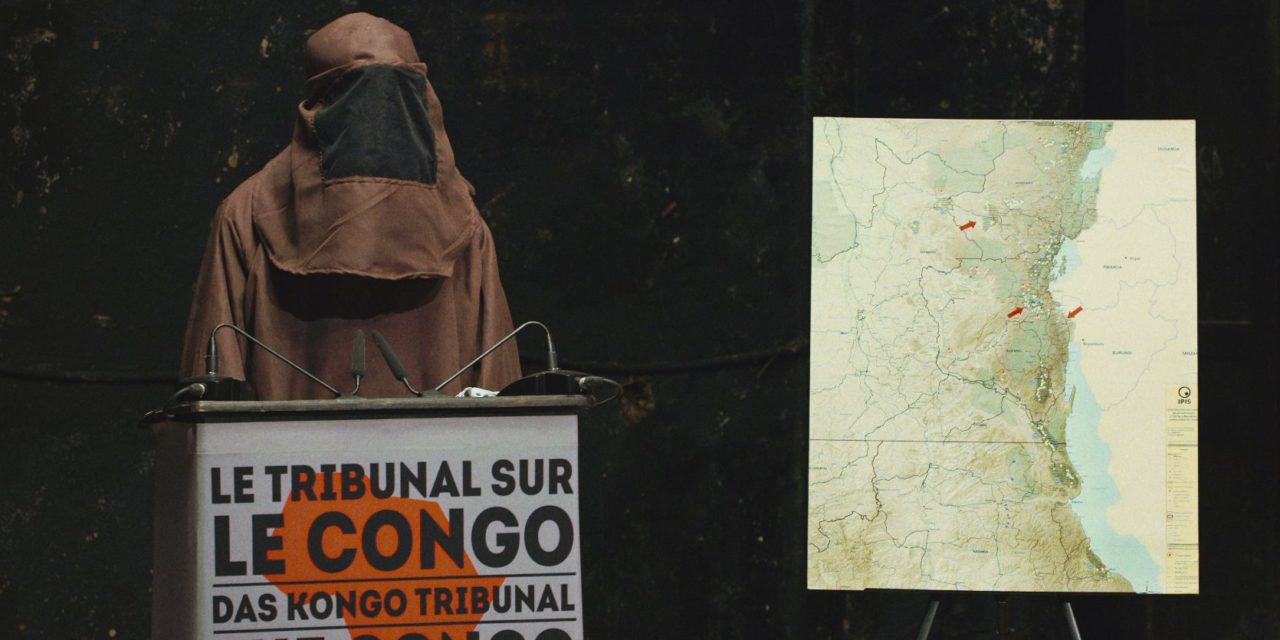

One of the few court hearings to address the crimes committed in Eastern Congo was actually an art project: theatre and film director Milo Rau’s The Congo Tribunal has had a significant impact and cost two ministers their posts.

Mr. Rau, for your political piece The Congo Tribunal, you brought victims, perpetrators, and witnesses of the armed conflict in Eastern Congo together and staged trials with real judges and lawyers. The whole thing was then turned into a documentary that was released in cinemas in 2017. What does political theatre mean to you?

That’s a complicated question. We could argue that the term theatre does not really apply to The Congo Tribunal. I’m more interested in creating a symbolic space for action: I wanted to represent the conflict and also provide a model for justice that simply does not exist in politics. Officially, the Congo is a “post-conflict zone,” though the war that cost more than five million people their lives is by no means over. Basically, all sides deny there is even a war. So my goal was to create a space in which the reality of this war could be described; a space for empowering all the people involved, above all the victims.

How did you get ready for the project and how did you approach those involved?

We worked with a lot of different interest groups and it took us over two years. We had Congolese and European lawyers, civil society activists, people from the government, rebel groups and companies. Over many months we looked into three cases–one massacre and two mass displacements–talking with experts and eyewitnesses. I am still amazed that we were able to do it all in the middle of a civil war zone.

Milo Rau (left) at the showing of the film in Mushinga village in South Kivu. | Photo: © Vinca Film

The entire tribunal lasts 30 hours. Did you find that situations tended to escalate when victims and perpetrators met?

Not in the sense that they tried to attack each other in the courtroom. We were ready for the possibility though and had good security. The arguments escalated all the time, but that was the whole point.

Did the participants receive clear instructions beforehand?

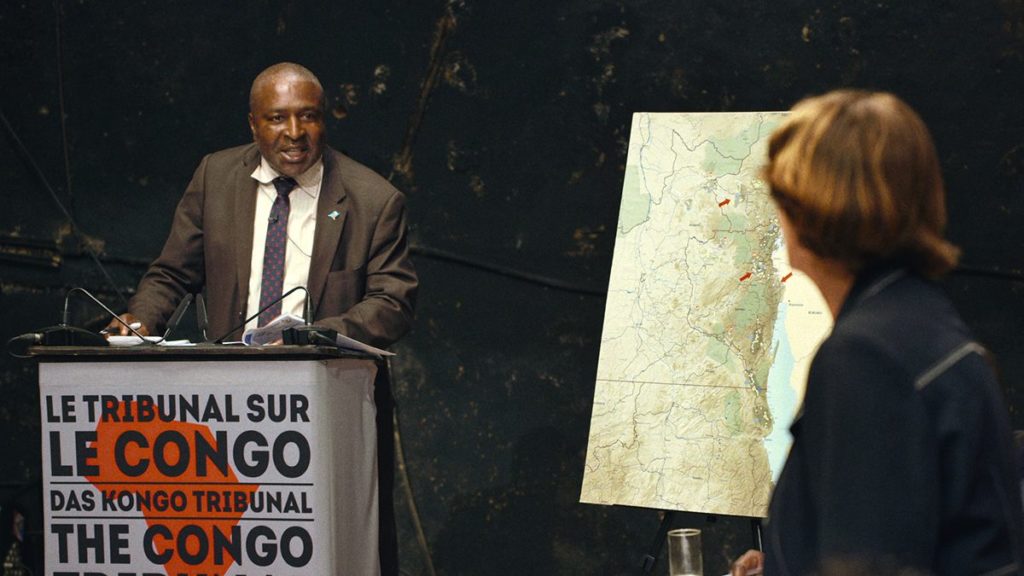

Yes, just like in a real court case. The President of the Tribunal, Jean-Louis Gilissen, was one of the founders of the International Criminal Court in The Hague. When I asked him why he presided over The Congo Tribunal, he said, “because this trial would never have been possible in The Hague.” His colleagues in The Congo Tribunal were also real judges and lawyers. Head investigator Sylvestre Bisimwa, for example, is the president of the Congolese Bar Association.

Except that the verdict was not legally binding. Did the tribunal actually change anything?

Apart from the tribunal, there has never really been a comprehensive trial about the events that took place during the civil war in Eastern Congo. This art project has had a unique effect: ministers were dismissed and the tribunal has become a model for civil jurisdiction in the region. There have already been subsequent tribunals. We no longer carry them out ourselves, but we finance them through crowdfunding and private sponsors and lend a hand legally and organizationally. The Kongo Tribunal archive page has a link for anyone who wants to help finance other tribunals.

That sounds pretty unusual for an art project.

In this case, art invented a new institution that became real. But if you look at the history of Western democracies, it’s not all that unusual. The German parliament was also simply called into being back in the day. In 1789, future members of parliament invented the French parliament with the words, “We are the nation.” The beginning is always marked by a quasi-artistic act of creation, of self-empowerment that later becomes an institution. In the West, we have become quite accustomed to the fact that such institutions exist and we can simply turn to a court if we experience an injustice. This was not the case 200 years ago, and it is not the case in many parts of the world today. A global economy–and that is what The Congo Tribunal is about, the crimes of multinational corporations–requires global jurisdiction.

Adalbert Murhi, then mining minister of the province of South Kivu, is questioned by the jury in The Congo Tribunal. He was later forced to step down. | Photo: © Vinca Film

How does it feel to know The Congo Tribunal will be shown at the Roma Europa Festival?

We have already performed a few pieces at the festival. Now, for the first time, a film of mine will be shown there. I think it is wonderful!

Was there a particular reason that the tribunals took place in the Congolese city of Bukavu and in Berlin’s Sophiensälen theatre?

Absolutely. At the end of the 19th century, the Congo was created, drawn up on a map and awarded to Belgium, at the Congolese Conference in Berlin. That was when the people’s misery began. The Congo has always had the raw materials the European economy needed: first rubber, later uranium for atom bombs, then gold, coltan et cetera. Paradoxically, the Congo’s wealth is also the source of its misfortune. This historical dimension was why I wanted part of the tribunal to take place in Berlin, as a way to investigate to what extent the EU, especially German and Swiss corporations, were involved in these crimes. And Bukavu, at the center of the civil war zone and as a place where many massacres have taken place, was imperative.

In view of current world events–is it even possible to change anything for the better?

Yes, we can change things. Look at the Corporate Responsibility Initiative in Switzerland. It requires companies to be transparent about where they source their raw materials from and the prices they pay for them. I really think we can change anything if we set our minds to it!

This article originally appeared in Gothe Insitute and has been reposted with permission.

Translated by: Sarah Smithson-Compton

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Eleonore von Bothmer.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.