The University of Hawaii at Manoa (UHM) is internationally recognized as the best university-based center for the study and practice of Asian performance (outside of Asia), offering a wide-ranging Asian theatre curriculum: theory and history courses, voice and movement courses—delving into the intricacies of jingju, kabuki, kyogen, noh, randai, and wayang kulit.

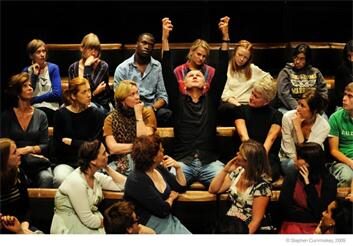

Each year, students have the opportunity to undergo intensive, year-long training in a traditional Asian theatre form with renowned practitioners who have spent their lives mastering the form. This arduous training—immersing students in the history and culture surrounding the art form, as well as the theatrical praxis—culminates in an English-language production of a traditional play.

For someone not from Hawaii, the practice of Caucasians learning and performing non-white theatre forms may seem like cultural appropriation—but in Hawaii, this is categorically untrue and inarguably an outsider perspective. Few people born and raised in Hawaii could ever dream that sharing an art form could be an act of aggression, with negative implications. For the majority of the people of Hawaii—a radically ethnically diverse populace, where most people identify as mixed race and only 24% of the population is white—there can be no possibility of appropriation since there is no ethnic majority.

In Hawaii, since about 75% of the population is non-white, the only instances of racism are often against haoles (a Hawaiian term, originally designating a “foreigner,” which in popular contemporary use denotes Caucasian.) This reversal—where the typical ethnic majority becomes the minority—makes Hawaii, our theatre, and our cultural artistic practices unique; the same rules do not apply here.

UHM has a long and excellent tradition of bringing conventional Asian theatre forms to its local audience, with student casts which reflect the community makeup: utterly diverse. (As far back as December 1963, Benton The Thief, a kabuki play, premiered at the newly built Kennedy Theatre, designed by architect I. M. Pei, of Louvre glass-pyramid fame, and named for the recently assassinated President Kennedy.)

Most recently, UHM students performed in Power And Folly, an English-language production of three traditional kyogen plays, directed by Dr. Julie Iezzi, with months of studying under kyogen masters from Japan. The experience of learning another culture and traditional art form is invaluable. As we seem to be increasingly threatened with boundaries, insularity and alienation, and the narrow-minded parochialism of inward-looking populist mentalities, students’ experience at UHM seems more crucial than ever.

The following is my interview with Christine Lamborn a self-described haole, an MFA candidate in western theatre, and an accomplished western stage actor. Christine shares her experiences and insights learning Japanese kyogen at UHM this past year—a painstaking process of meticulous rehearsal and training, which led her to a new perspective on the universality and specificity of art, the shared language of the human spirit, and the importance of gaining cultural insights.

Taurie Kinoshita: Prior to the performances in late April, what was your experience with kyogen?

Christine Lamborn: Very little. I had heard of kabuki and noh, but I hadn’t been exposed to kyogen.

TK: What was the training process like?

CL: The training process was very intense because kyogen is stylized and has existed since the 14th century in Japan. So, for over 600 years, this form has thrived and continued because of the families in Japan who have kept it alive. We first studied with Professor Julie Iezzi in the Fall semester of 2017. Everyone interested in participating in the production was required to also take a kyogen voice and movement class. This is because, in kyogen, there are ways of standing, walking, sitting—general movement—kata. In order to make the rehearsal process go more smoothly, we needed to learn the basic kata.

Think of it this way: professional kyogen actors usually make their debut by age four and have received training since they were maybe 2 ½ years old. Our rehearsal process was extremely intense compared to most western theatre productions—but not, of course, compared to kyogen itself. Traditional Asian theatre artists study and train their entire lives from a very young age. While a year of training for a single 40-minute show may seem severe to the average western theatre performer, for Asian theatre forms, this rigor is necessitated: to learn an entirely new way of stylized movement, to gain insight into the meaning of the form, to respectfully engage with the form. Just learning the dialogue from a kyogen play would not even begin to do the form justice—psychology and text are not the focus.

TK: In addition to learning the kata, and taking classes while rehearsing, describe other aspects of the process.

CL: I was in Two Lords; this was the most traditional piece of the three in Power And Folly. I believe it dates back over 400 years.

We first began with the learning the majority of the script in Japanese; I do not speak Japanese…

We learned Japanese in order to mimic the specific inflection, pitch or tonal changes of the master-teacher. There is no written way of distinguishing when the pitch changes in this art form—it’s a living form passed from master to student over centuries. We listened to videos, practiced with Dr. Iezzi, studied with the two kyogen masters who came and did the residency with us. The master teachers demonstrated from memory how the tonal changes were different. It felt almost like a “line read” (which is a taboo in western theatre but made perfect sense in this situation.)

Along the same lines, the physicality of the art form is very precise. How to turn your feet when moving, how to keep your body in a certain alignment, how your hands should be in different positions depending on your character type: everything is precise and calculated. From a slight turn to a bend, each movement is significant and important. Since this is a tradition that is passed down from grandfather to grandson, the memory and interpretation can vary from one generation to the next very, very slightly—so whoever is teaching you at that exact moment, whatever they remember and tell you to do is correct. While the next day someone else maybe teaching you and they may remember something slightly different—whatever they tell you to do is also correct. Yesterday’s instruction was not wrong but today’s instruction is the most correct. It’s a tradition and a living art form. The master teacher can make small adjustments and understand those adjustments, yet remaining consistent is vital and challenging. Having a “yes and…” mentality is necessary. Of course, writing down stage directions can be helpful to a certain point—but being bogged down in exact stage directions or movements from the previous day will do a discredit to you in the long run. There is a profound depth to this type of methodology.

TK: How successful do you feel you were and how successful was the show overall?

CL: I’m thankful and grateful for this opportunity. This is such a unique experience for me since I’ve never participated in an art form like this before and having the opportunity to study under a specific kyogen family here at UH Manoa is something I would never have been able to do at any other university in the United States.

Theater is alive and there’s always room for expansion and improvement. If I were to continue studying and to continue performing the show, I’m sure that over time it would constantly improve. For a year of study, I am very proud of my experience and my performance. Even more significantly—I have the sense that the master teachers were pleased with what we were able to accomplish—and that is satisfying.

TK: The goals of a kyogen in Hawaii are different than they are in Japan. Could you speak to these differences?

CL: I’m not sure if I’m the best person to explain this but I feel that, at least in Hawaii, the goals for producing kyogen are to help share a culture and art form to people who may not be as aware or experienced with this specific type of theater. We see the universality of the human spirit: we all laugh and cry at similar situations. The community gains a shared experience—across oceans, cultures, and across time. There is also a purely academic (as opposed to educational) purpose: to help students who are interested in this type of theater (that may not have the ability to go and study on their own in Japan) gain valuable exposure.

TK: What would you say to people who advocate “only Japanese people can do kyogen” and “no actor of color should do Shakespeare.”

CL: Nothing should be off-limits for anyone based on things that they are not able to determine themselves—such as, but not limited to: race, gender, or where they were born and raised.

To share your culture with another being is a great gift. To help someone understand something about a different culture especially its traditions and beliefs, in my own personal opinion, is something that this world needs more of. Fear comes from a lack of knowledge and understanding. Hate can rise from fear. We must work towards sharing our knowledge, empathy, understanding, and also actively strive to explore the unknown or the foreign.

TK: Anything else you would like to say about kyogen, the process of rehearsing or being a western actor who performed traditional Asian theatre?

CL: If you ever get the chance to study another theater form I highly encourage you to take part in it with an open mind and not to be bogged down by any previous training or knowledge.

TK: How did audiences respond?

CL: The audiences responded with laughter and being enraptured by the plays and form. Even the audiences who didn’t have access to a lecture/demo prior to the performance didn’t have any difficulty understanding the humor and comedy of the pieces.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Taurie Kinoshita.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.