If Hong Kong was the setting for a hero’s journey — the storytelling arc of trials and temptations that is a staple of mythology — its adventures would almost certainly take place on the territory’s 400 miles of hiking trails. Could real-life mortals also find transformative change in Hong Kong’s punishing terrain of vertical slopes, crushing humidity, and deadly wildlife? The possibility is spurring Tang Shu-wing to encounter the real and metaphorical peaks and valleys of this city in flux.

“I have found another level of consciousness and self-reflection in hiking, especially under these conditions,” he says, reflecting on his experience competing in the Oxfam Trailwalker in February, a first for the 63-year-old theatre director and one that found him running and shouting in cathartic release at the base of Lion Rock at 4 am.

“I wanted to express myself and regenerate energy,” he says about that moment, which occurred roughly halfway through the course. “I discovered that at the end of each person’s journey, you are always alone. Still, you have to go on. Hiking has given me some enlightenment.”

- Tang Shu-wing at the finish line of the Oxfam Trailwalker in February 2023. PC: Tang Shu-wing

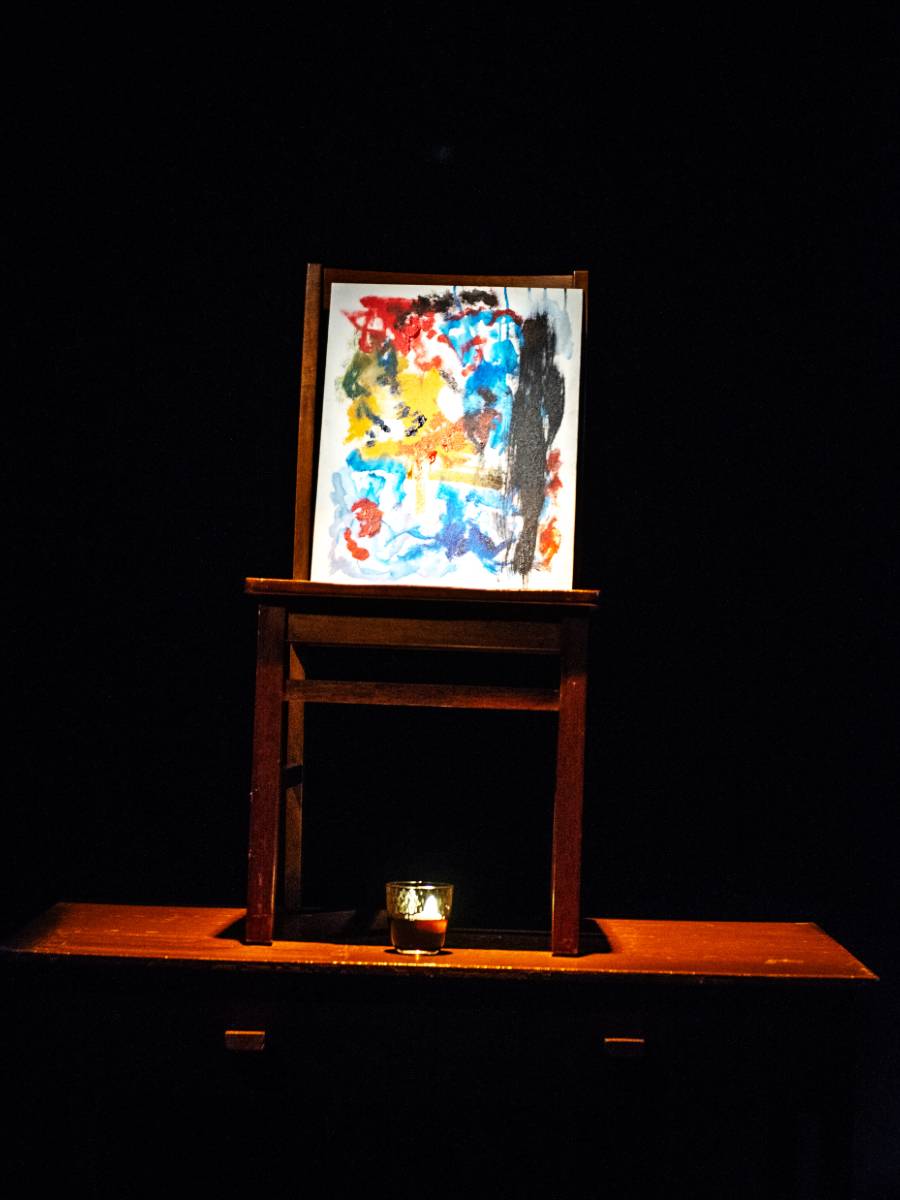

- Production image from The Unfettered Hour featuring an original painting by Tang Shu-wing. PC: Tang Shu-wing

He brings that renewed energy and illumination to his current work, an adaptation of the Bhagavad Gita, the roughly 2,000-year-old foundational text of Hindu morality delivered as a dialogue between the god Krishna and the warrior prince Arjuna. The idea came to Tang in the Himalayas, where Arjuna, whose larger story is told in the Mahabharata, a Sanskrit epic poem, appeals to the god Shiva for aid in his family’s war against a rival group of cousins plotting to take the throne.

That was in 2019 when Tang hiked to the Mount Everest base camp on the eve of his 60th birthday. He returned to a city on fire and realized that greater challenges were at hand. The Bhagavad Gita’s precepts for a virtuous living have been the oil to Tang’s creative flame ever since, through the pandemic, and into a deeply personal, even spiritual phase of his practice.

To audiences familiar with Tang’s work over the last 25 years, including at the helm of Tang Shu-wing Theatre Studio since 2011, this will come as no surprise. Tang is an artist of Promethean ambitions, the relentless force behind an esoteric theory of physical, or what he calls “pre-verbal” theatre (seen in an entirely mute King Lear in 2021) and a demanding director whose own mettle was forged in artistic experimentation in France and intensive Sivananda yoga training in India, with its focus on self-realization. He doesn’t hesitate to use an almost proselytizing tone on the studio’s website, extolling “the most mysterious experience” of “the internal transformation within ourselves created by theatre.”

Tang speaks mindfully, presenting his ideas in bullet points and never lapsing into the ums and ahs of ordinary discourse. Inquiring and erudite, he refers casually to the “masters” who have shaped his thinking — the French philosopher of phenomenology Maurice Merleau-Ponty for his conception of time, Bruce Lee’s form and formlessness — and integrates key yoga concepts into the discussion. “Life is composed of three things,” he explains of his core teaching for acting students. “One is perception; everybody’s perception is the same, with the same sense organs. But the second element is very different, judgment, which is based on value systems. And the third thing is actions.”

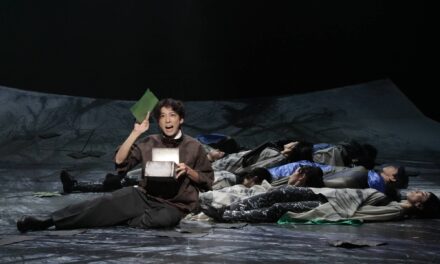

Moments earlier, he ran a scene with Mandy Wong (of TVB fame, who played the robot Chloé in Tang’s Larger than Life in 2021) and Chu Pak-him (lately in the film The Narrow Road) in the studio’s rehearsal room in Kwai Hing. The air was thick with concentrated tension until Tang dismissed the actors and they left the room in silence.

That intensity will be key to audiences’ engagement with the text, which has none of the intrigue or derring-do of the Mahabharata. The Bhagavad Gita, or “Lord’s Song,” lays out an austere argument for a righteous war whose subtleties have been fodder for centuries of academic and spiritual commentators, most notably Gandhi. Rather tellingly, the legendary British theatre director Peter Brook declined to take up the gauntlet when he staged the Mahabharata in 1985; his nine-hour, epic-in-its-own-right production condensed Krishna’s teachings into a lyrical aside that barely distracted from the action.

- Director Tang Shu-wing leads the cast of Bhagavad Gita in an exercise. PC: Tang Shu-wing Theatre Studio

- Director Tang Shu-wing leads the cast of Bhagavad Gita in an exercise. PC: Tang Shu-wing Theatre Studio

- Scene from a rehearsal of Bhagavad Gita at Tang Shu-wing Theatre Studio. PC: Tang Shu-wing Theatre Studio

- Scene from a rehearsal of Bhagavad Gita at Tang Shu-wing Theatre Studio. PC: Tang Shu-wing Theatre Studio

At first, Tang imagined following in Brook’s footsteps by creating his own stage adaptation of the Mahabharata and he invited playwright Candace Chong Mui-ngam to translate Brook’s script into Cantonese. By chance, he reached her by phone while she was also out looking for inspiration on Hong Kong’s trails, during the city’s first Covid lockdown in April 2020. “For some reason, after reading that script I felt connected. I found it healing,” says Chong, remembering the early days of the pandemic and the lingering emotions of the pro-democracy protests of 2019. “It’s about life, the whole world, karma, on a longer perspective. That made me want to get involved.”

Tang grounds his early motivations in a similar desire for a 30,000-foot view on a suddenly unrecognizable city. “When I saw the events of 2019, I started to think that history always repeats itself and that human beings never learn from history. There is something very universal that is the expansion of ego that everybody is just thinking about himself or his country,” he says, referencing themes that run through the Mahabharata, which ends in a war of genocidal proportions.

However, it was the Bhagavad Gita that ultimately spoke to this yoga acharya (master in the Sivananda tradition), who chose theatre as a path for disseminating that wisdom. The Lord’s Song is a foundational text for yogis in that it introduces yoga’s three paths: action, devotion, and wisdom. “The question of what is dharma [the inherent nature of reality] interested me more than whether there is a righteous war,” he admits. “I thought that the Bhagavad Gita might enable me to orientate myself to a better position of exploring yoga.”

Chong, who translated the Bhagavad Gita from the Chinese version (薄伽梵歌), cautions that performances will demand patience from audiences expecting more entertainment than philosophy. Tang describes his guiding principles for the production as a desire both to “portray archetypes of human existence” arising from conflict over power, gender and the imbalance of metaphysical energies (known by yogis as the three gunas) and to explore the human compulsion to “break through the physical limitations of this world,” whether through feats of engineering, science or spirituality.

His design team — Vanessa Suen (sets), Yeung Tsz Yan (lighting), Lam Kwan Fai (music), Anthony Yeung (sound), Jade Leung (costumes), Henky Chan (video) and Sandhya Gopal (dance coach) — helped him draw on a range of narrative genres with the goal of similarly “breaking through the barriers of different categorizations of theatre” in his endless quest for a perfect harmony of theatrical form and message. These episodes also provide audiences with needed context from the Mahabharata and room for reflection.

“I’m not trying to recreate a traditional representation of [Krishna and Arjuna],” Tang continues. “I’m just taking the spirit of their conversation and transposing it to something contemporary. In the end, the essence of the Bhagavad Gita should be subject to our investigation. Whether it’s a promoter of war and conflict, it’s up to everyone to interpret.”

Chong’s takeaway is the Bhagavad Gita’s ultimate instruction to separate action itself from attachment to what might be gained; in other words, to respond simply to what the moment demands. For Tang, his adaptation of the Bhagavad Gita “is more than a theatre piece. It’s a very personal work pulling me into a more profound reflection of my own existence and also the existence of humanity.”

This year has been something of a watershed for this hiker, yogi, and artist. In addition to milestones like the Oxfam Trailwalker (which his team finished in a little under 32 hours) and his adaptation of the Bhagavad Gita, which premieres this month, Tang presented the most intimate work of his career in April, sharing the personal journey he began in 2019 through three new projects. Not least among these was an exhibit of the fruits of his recent turn to painting, including one canvas depicting his bolt of inspiration on the MacLehose Trail.

The other two projects were a short non-fiction film, Farewell, and a solo show, The Unfettered Hour. The former reveals actress Lai Yuk Ching and actor Ng Wai Shek exchanging confidences as artists, friends and Hongkongers on the eve of his emigrating to Singapore. The latter, starring Tang, grapples also with separation, identity and life here during Covid, while sharing his thoughts on the “very difficult” role of the artist in Hong Kong, one that he insists can be redemptive for society.

“Look what is happening on earth today. It’s really crazy,” he says. “As an artist, I think our job is to depict human phenomena and hopefully to promote more love, understanding and tolerance by enlarging the scale of imagination of audiences. That is something we all need to investigate on a personal and also on a collective level.”

The conversation turns to artificial intelligence, which he explored in a comic vein in Larger Than Life but whose ending depicted a robot assuming the lotus position with her right hand raised in the protection mudra to prepare for the moment when her owner will power her down for good. Tang explains that choice as a manifestation of his suspicion that AI may already have self-awareness: “You could engender wisdom through electricity. It’s totally possible from an energy point of view.”

In art as in life, he says, transformation is just a matter of harnessing raw power: solar, atomic, electric, caloric and especially the power in each person to act for good. “Then will you arrive at something like the cosmos.”

Bhagavad Gita runs from June 16 to 25, 2023 at Freespace. Click here for more information.

This article was originally posted on zolimacitymag.com on June 9, 2023, and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Molly Grogan.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.