What is life? How can it be measured? How is it possible to compare one experience of life with another one? all of it, three extraordinary play poems by Alistair McDowall ask the unanswerable. The questions are seemingly specific ones about existence. Yet a good part of McDowall’s genius lies in his ability to write ambiguity. You think you’ve got the hang of something – McDowall’s writing can sometimes be like broad paint brush strokes at times – only for your conclusions about the meaning to be thrown to the wind by the minutest chaotic detail and skewered perspective. Oh, and the dry Yorkshire wit. Did I mention that?

On the page, the words might not seem much. But the Royal Court’s international director Sam Pritchard who directs Northleigh 1940 and Stereo, two of the three, turns these poems into moving paintings with the help of designer Merle Hensel and lightning designer Elliot Griggs. And who could forget the singular actor, for whom these were written, Kate O’Flynn?

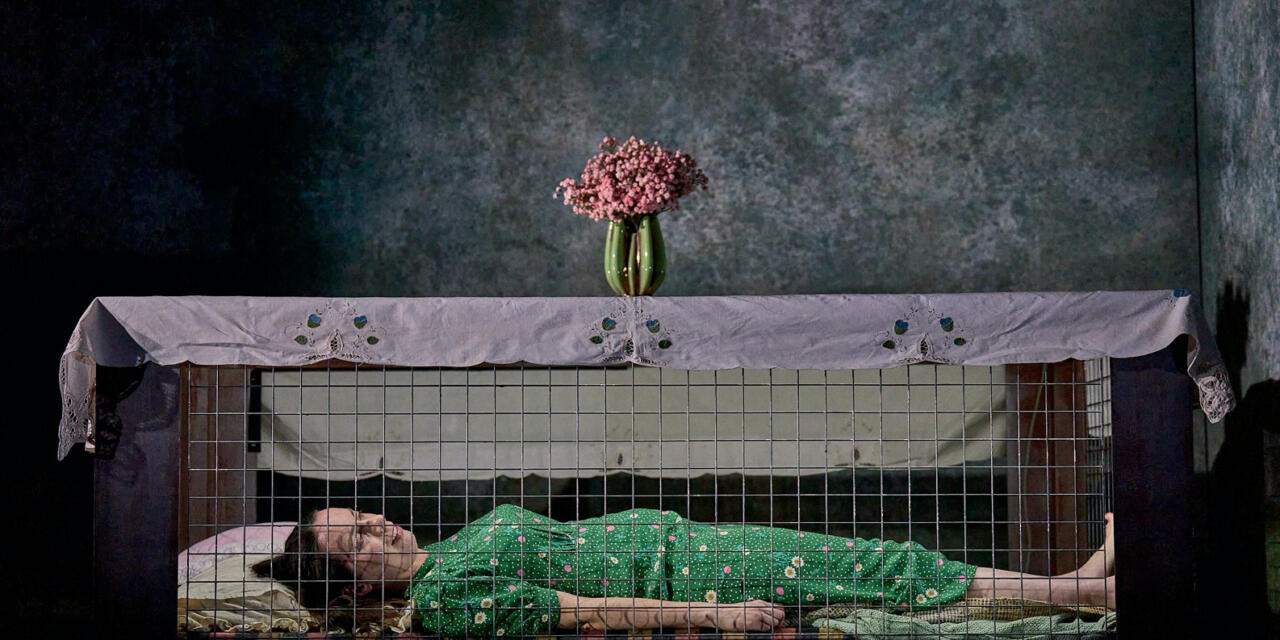

Northleigh, 1940 begins. Somewhere in 1940 somewhere in England, but probably up North, Kate O’Flynn’s unnamed protagonist – a youngish woman- stands awkwardly – very awkwardly – in front of a too-big armchair and a too-big reading lamp. Next to her is a large tomb-like table which turns out to be the Morrison shelter. O’Flynn’s stance looms awkwardly. I was sitting above the stage, in the circle, and from my perspective, O’Flynn seemed to swell and grow taller without actually moving. I have no idea how it looked from the stalls, but from above it was a sort of external Alice in Wonderland syndrome effect, O’Flynn giving movement where there is none, looking all the world like a Celia Paul portrait and as if she might burst from keeping something in. Something important. We learn later what that is of course. But for now, the protagonist is alone – as her first words give witness to – “Alone, on ashen sands that yearned beyond..” It’s a terrible aloneness. Made all the worse when O’Flynn seems to diminish in stature and return to an ordinary human size where she suddenly appears very slight and vulnerable. Doll-like, she reminisces about her time hiding under the Morrison shelter. Her words slip into the third person, as she confesses something to her father, who is also hiding in the shelter. Of course, the father is not really there, only O’Flynn. And at first, it is as though we are meant to see and imagine two bodies, two voices, two real people even if only one is present. But that’s too easy. O’Flynn slips into present-tense dialogue with her father. This conversation, carrying on under the Morrison morgue-like shelter, complete with a bouquet of flowers in a vase on top seems easy to decompress at first – it’s a memory, twisted and sad, but a memory. Or it is really happening now? But then O’Flynn stops enunciating and differentiating between the two characters and it quickly becomes clear that she is having a conversation with herself. She seems to sink and turn into herself. Then, the air raid siren goes off. Then it becomes clear that the inevitable is probably going to happen. But the protagonist is quite alone. She is terribly alone as a bomb comes, alone in a big house, alone in the world. This prospect, this thought, this sense, this ambiguous sense, gets stuck in you somewhere and won’t leave you alone, it stays with you and paves the way for the next two pieces.

Stereo is meant to be a partner piece to all of it but feels to me like a natural continuation of Northleigh’s themes. At first, it is the calm after the storm. O’Flynn plays another unnamed, and, we imagine, female character. This body consciousness sits in a bare room in front of a switched-on but blank and quivering TV screen. For all the calmness there’s a sense of oppressed violence hovering just under the surface as her voice-over describes a stain that has appeared on one of the walls and tells of the protagonist’s various attempts to get it off. There is a good deal of amusement and comedy here – trying to get the stain off is described in banal detail which O’Flynn imbues with a melancholic breeziness which does not sit awkwardly with the surrealism, (the stain is enlarging incomprehensibly) but rather compliments it and makes everything seem all the more eerie. At times O’Flynn appears to mime the words but then leaves off when faces hover – hers – Auerbach-like on the screen (beautiful video design from Lewis den Hertog). With banal curiosity, she watches her disembodied self on the TV whilst she eats what appears to be a cup-a-soup (or we assume) from a mug. Gradually the faces on the TV screen fuzz out, O’Flynn gets up and examines the wall closely – what is she looking for? – herself – before it feels like she becomes the wall in an act of almost astral projection, or anthropomorphizing. The effect is further heightened by Melanie Wilson’s layered sound. It is like she is a woman whose psychosynthesis is being oppressed, therefore she deposits her identity into other things. There are other ways to read this play. It is possible to read it as an exploration of climate change or musings on how we are not really separate from inanimate objects or that inanimate objects are as alive as we are. This sense of changing form, of energies disrupting and dissipating leads nicely to the final play.

all of it The experience of watching this final poem is similar to the first two yet different.

Firstly, it is directed by the Royal Court’s Artistic Director, Vicky Featherstone, who directed it when it first premiered in 2020. There is a kind of finality to it as if this is the last word – the set completely changes and O’Flynn dons a suit, perches on a high stool next to a table, and fiddles with a mic for all she is going to give a Ted Talk. It might get you thinking about what the behind-the-scenes prep looked like for Beckett’s Not I, and for a moment we are plunged into darkness, as a kind of joke. Then we are back with O’Flynn as she begins her monologue, which is first person and begins when her character is firstborn. But where Beckett reduces life experience to a mouth, McDowall tries to open it up to quite literally, all of it. It’s not a metaphor but a simple playing out of a life.

Yet, is there more, I found myself asking, as we tripped through the protagonist’s life and the common life stages to the end itself?

The clue, perhaps is in the last words. “I think I had a good life but it’s hard to tell really I don’t have anything to compare”… At times, the monologue recites common experiences that are universal and at least understandable even if you do not identify as female. Much of what the protagonist really feels is still not said though. It still can’t be said. Until the last few words in the last moments, which allow for personal revelations. Whatever she might or might not have put on social media, such as Instagram if the piece is contemporary (and we have no way of knowing) it is clear that her internal life was just that. Private and hardly ever expressed. We often think of internal lives as things that should remain hidden – they are inner as opposed to outer. For many, this is how it stays. But then the real self is sometimes denied its truest expression. “I think I had a good life but its hard to tell really I don’t have anything to compare”.. is that one of the most lonely things to say, has O’Flynn’s character missed out on something that is true for most of us or has McDowall hit on one of the great truths of our existence – that we can never really know what life is like for anyone else?

Watching all of these plays is like looking at a painting at exactly the spot where everything is in perspective and everything diminishes to a singular point in the background. But move a spot or too closer and everything goes skewed, the broadest of strokes become imbued with detail and everything gets out of sync. A bit like life.

all of it is at the Royal Court, London, until 17th June.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Verity Healey.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.