In the last twenty years, Antonio Latella has made a name of relevance for himself in Italy as an innovative theatre director. His work so far has generally focused on iconic plays by Chekhov, Shakespeare, Brecht and the like, staged with contemporary and minimal sets because his main attention was drawn to the actors’ bodies. Latella has repeatedly worked with unconventional body types – midgets, people with Down syndrome, people who are extremely skinny or obese – including his own, to expose the physical drama behind the scripted words of famous authors.

In 2014 he made a brave choice. For the first time, he applied his dramaturgical skills to one of the most famous and represented Italian playwrights: Eduardo De Filippo (1900–1984). On average, Italian audiences and critics have no problem whatsoever in applauding all forms of adaptations of foreign plays (Shakespeare’s comedies have been set in all times and places, for instance), but when it comes to twisting famous national authors like De Filippo or Pirandello, spectators tend to be on the conservative side. They expect to see realistic sets and academic acting. Latella gave nothing of the sort, and put the pedal to the metal fully in staging of Eduardo De Filippo’s Natale in Casa Cupiello (Christmas at the Cupiello’s – 1931) at Teatro di Roma. The dramaturgical work was effectively new and old at once. The novelty came from the fact that Latella stripped the play of all its naturalism, decorative elements, traditional costuming and setting, and placed the action in a black box that exposed the theatricality of lights moved by the actors and a few exaggerated props made of foam rubber. On the other hand, Latella showed true respect for the original play, as he did not change one word of the script. Actually, he went so far as to ask his actors to recite all the stage directions as written by Eduardo De Filippo himself in the published version of the play.

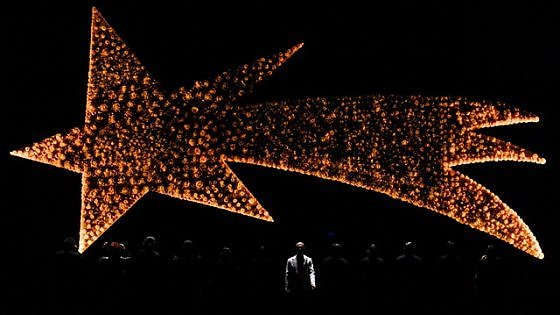

Act I is a breathtaking acting marathon. The stage is invaded in all its length and height by a gigantic comet. The whole cast – including those who will only have a spoken role in Act III – stand in line in front of the comet. Everyone is dressed in black and wears a sleep mask, except for the protagonist, Luca Cupiello, who wears a white suit. The first impression is immediately one of loneliness, as Luca stands out from the mass of his family and friends. The reassuring atmosphere of Christmas is already shuttered, as the huge comet behind the actors looks like an asteroid about to crash into planet Earth to destroy humanity. In fact, Latella’s intention is to describe the lack of real human communication in this low-income Neapolitan family in that moment of the year, Christmas, that by habit or tradition should be a celebration of unity and love. The cast revolves around Luca’s obsession to complete his “presepe” – the representation of the nativity so popular among Neapolitans. This obsession works as a blinding veil on Luca’s eyes, as he does not see all the dramas evolving in the household: the son is a no-good slacker who steals pocket money from his own family; the daughter has married a rich businessman but is planning to leave him for a penniless student; and his wife tries to glue together the pieces of this broken humanity, constantly risking a nervous breakdown. However, Luca is immersed in the creation of his presepe and cannot really focus on or talk about anything else.

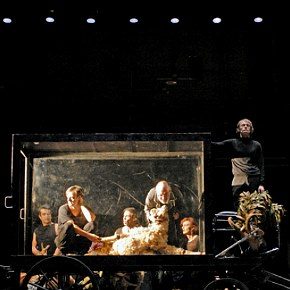

Finally, the comet lifts and disappears to unveil the empty stage. Empty except for one element: a vintage-looking hearse with glass walls. This kind of vehicle would traditionally parade along Italian streets pulled by four, six, or eight black horses. The number depended on how wealthy the family of the deceased person was. During Act II, for the most part, the job of pushing or pulling the hearse falls to Luca’s wife, Concetta. This strenuous physical action beautifully and tragically represents the burden suffered by Concetta’s shoulders. She is the real heroine who tries to fix things, while Luca is stuck inside the glass walls; a combination tomb and aquarium. All other characters surround the hearse, each of them holding, lifting, or tossing around the stage huge animals built of foam rubber. Each animal represents one of the meat dishes normally cooked for the long and rich Christmas dinner on December 24th – poultry, pork, and capon. Latella uses these oversized animals as metaphors for the characters’ roles in the family dynamic. The weight of the props (spectators can hear the sharp sound of an animal’s wooden feet stomping on stage each time an actor throws it to someone else) adds to the actors’ performance an element of fatigue. Their breathing grows more asthmatic. This short-breath feel perfectly matches the increasing anxiety of the drama.

Act III is probably where Latella detaches himself too much from the play’s original thread line; it is where the director’s ego shines too much, dwarfing the author’s intentions. In Act III Latella metaphorically kills Eduardo, although this could be a deliberate choice, as it is also the drama’s climax in which Luca Cupiello suffers a stroke and eventually dies. Luca’s illness is caused by the fact that he must finally face the family’s reality. The world of innocence he had constructed for himself up to that moment collapses. Emotionally challenged by the sad truth, Luca is unable to accept his failure as a father and a husband. Rather than accepting his own limits, he falls into a dementia-like state and dies. Latella builds the long mourning scene as a Flemish painting by Rembrandt or Vermeer. Women and men are clad in austere black dresses, while Luca’s flesh is exposed, catching and reflecting the stage light as if he were the focal point of the painting. The technical staging comes full circle because once again actors, who were totally still in Act I and feverishly moved in Act II, revert to an almost total stillness for most of Act III. If Latella’s real intention was to give a contemporary makeover to a masterpiece of Italian theatre, he surely succeeded. If he also wanted to provide the new generation of theatre-goers with an understanding of the immense value of Eduardo’s tradition and human lessons, he proved that it is possible to do so. People leave the theatre feeling that they have seen at once Eduardo’s very well-known play and Latella’s brand-new show, which is proof of the director’s ability to provide a convincing signature style without disrespecting the play’s authorship.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Raffaele Furno.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.