Bill Irwin greets the audience by conveying that the performance will be around 90 minutes (by way of reassurance, he admits). In truth, the performance zips by. Irwin dazzles as he pontificates, performs, and clowns around, literally, with the famously obtuse dramatist’s work. Recalling some of the touring Shakespearean recitals of the nineteenth and early-twentieth century, “On Beckett” is an entertaining and enlightening presentation of disparate texts from Beckett’s oeuvre.

Irwin pulls from both dramatic and non-dramatic works alike. He recites passages from prose pieces such as Texts for Nothing, The Unnamable, and Watt, and spends a great deal of time discussing a work that became a mainstay in Irwin’s career, Waiting for Godot (is it God-oh? Or Go-doh? Irwin starts with the former, and then sticks with the latter). The performance as a whole is a tribute to both the great Irish dramatist as well the sterling career of one of the United States’ greatest living clowns.

Indeed, it is the relationship between the two, Beckett and Irwin, that informs the story of “On Beckett.” Irwin grapples with the difficulty of Beckett’s texts, and how they both invite and disparage interpretation. One of Irwin’s favorite and frequently used words in the performance is “or.” As he makes one point about Beckett, he’ll hedge and invite another, opposite response, holding the vowel, “ooooooor,” as he contradicts himself.

The performance welcomes the audience into an actor’s response to difficult texts. It showcases the interpretive questions an actor must resolve—chiefly, the question of desire. what does the character want?—in order to make meaning out of the passages. How does an actor take words from Beckett, the same that have been deviled over by academics ad nauseam, and express them through the perspective of a flesh-and-bone character?

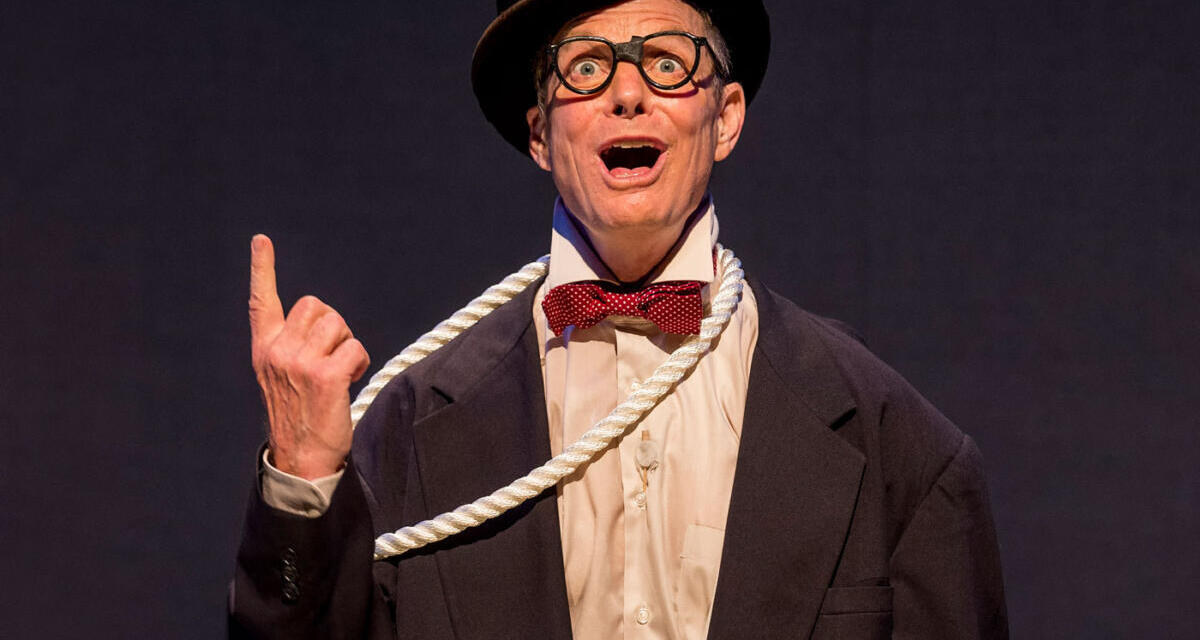

Even with the texts not written for the stage, Irwin demonstrates there is something certifiably dramatic (i.e. actable) about the characters. They belong in front of an audience. That point manifests via Irwin’s background as a clown. He captures the ticks, quirks, mechanical gestures, posture, and pathetic quality of the characters who babble about. Throughout the piece, Irwin adorns the vestiary icons of the clown: baggy pants, floppy hats, suspenders, and ill-fitting jackets. He even showcases a series of bits, what he discards as “clown schtick,” that had the audience roaring with laughter.

Really, as “On Beckett” gives a masterclass on the art of Beckett, so too does it on the craft of the clown. Irwin so gracefully embodies the buffoon which such simplicity that it’s hard not to grin from ear to ear as he breaks down small choices, like how to wear a hat in a dozen ways. He conveys some “clown theory:” namely, that to be a clown is to imagine how things ought to go (which he demonstrates by climbing up and down a makeshift staircase) and how things actually go (he then stumbles down the same set of stairs).

All of this reveals the mystery behind the art, yet it does not ruin its effect. The audience laughs all the same, even when Irwin tells us exactly what’s to happen next. In turn, Irwin’s presentation of clown works invites us to see the connection to Beckett that has made the actor such a natural fit. Beckett’s characters are clowns. They ache in their bodies. They fail to express themselves, move or act or even stay still.

Through all this, Irwin teaches us about Beckett in a way almost no one else could. He pontificates brilliantly about the works, adding his own personal musings and passions into the mix. He’s so persuasive in his lecturing that, late in the performance, as he’s musing on the political significance of Waiting for Godot, we almost forget to notice that Irwin looks ridiculous. He is dressed as a clown. His baggy pants swallow his fame and remove his dignity. That image alone captures the ineffable quality of Beckett, who captured some of humankind’s most existential questions through the image of debased clowns.

“On Beckett” at the Emerson Paramount Center, October 26-30, 2022, ArtsEmerson.org

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Matthew McMahan.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.