If nothing else, you have to admire the chutzpah of Robert Icke’s Oresteia, which tries to collapse the 8-hour, 3-play action of Aeschylus’s monumental Oresteia—a founding work of Western drama about cyclical family revenge—into a single 3 ½-hour contemporary domestic crime-drama. At New York’s Park Avenue Armory, Icke’s Oresteia (originally staged in London in 2015) plays in repertory with his Hamlet, reminding us how much Aeschylus and Shakespeare have always spoken to each other. Vengeance, family betrayal, the slipperiness of truth: nothing dated about any of these works’ shared themes. Unlike Icke’s Hamlet, however, which soars on Alex Lawther’s lead performance despite some off-the-wall directing choices, his Oresteia is implausible, fruitlessly mystifying, and at times downright gaseous.

Aeschylus’s Oresteia, to remind you, dramatizes the murder of king Agamemnon by his wife Klytemnestra when he comes back victorious from the Trojan War. She avenges his killing of their daughter Iphigenia 10 years earlier, when a prophecy said her death was the price of favorable winds to Troy. The couple’s son Orestes later murders Klytemnestra to avenge Agamemnon, and Orestes in turn is ruthlessly hounded by mother-avenging deities called Furies. In the end Orestes is acquitted in an apocalyptic trial that sets male against female, human against god, sky forces against earth forces, and glorifies Athens’s religious and judicial institutions. The goddess Athena, acting as judge, breaks a jury tie in favor of Orestes because, she says, she lacks a female parent and tends to favor males.

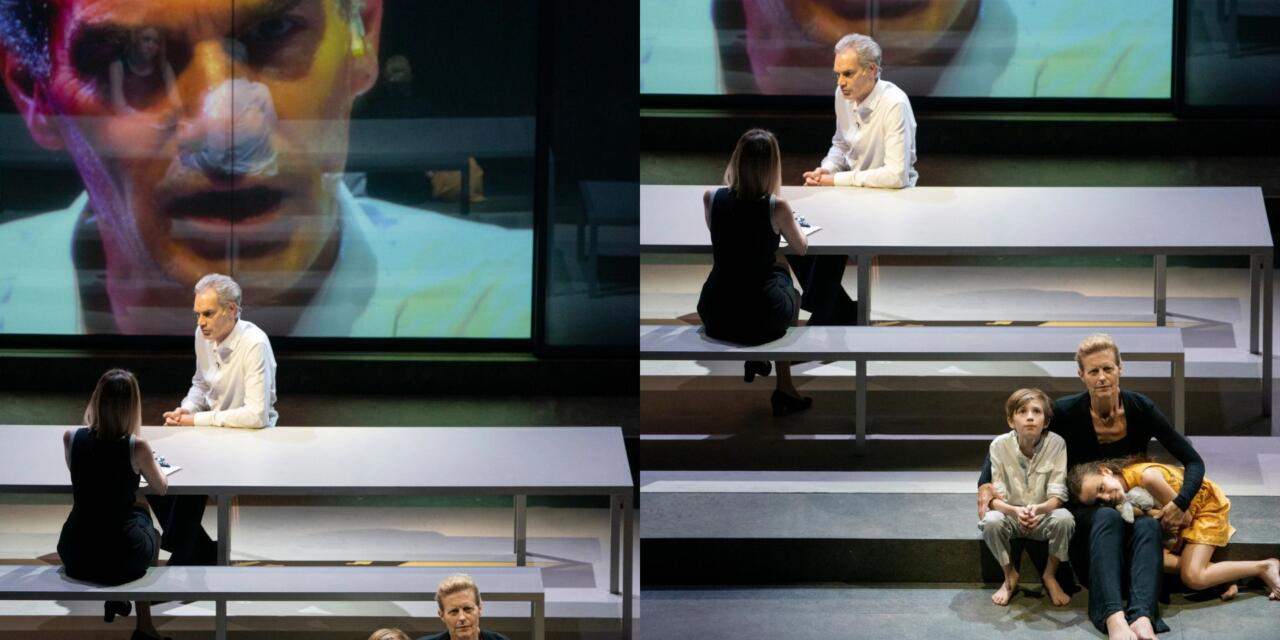

Icke’s Agamemnon is a self-assured guy in a business suit (played by Angus Wright) who does TV interviews, has a house with modern fixtures, and kids who listen to The Beach Boys. He’s not a king but rather a religious zealot and general who got himself elected Prime Minister (or something—it’s vague—“You were a controversial choice. An unpopular choice”). We see him manipulated by his brother and others into believing cryptic “communications” and “signs” that further their war aims, including the demand for his very cute daughter’s death. His faith is supposed to explain why this loving, modern dad, who dandles and fondles his daughter in affectionate domestic scenes, would actually hold her on his lap while a toady doctor administers a lethal drug-cocktail to her. Well, I don’t believe that for a second, and have trouble believing anyone else in the audience does either. Yes, fathers occasionally kill their children, but not this sensitive guy, in this contrivedly ruthless way.

Again and again, Icke’s Oresteia violates the psychological reality that it carefully establishes in order to push on with its violent plot. Every pivotal event in it—closely hewing to its mythic source material—is consequently far-fetched and absurd.

There are pleasures. Anastasia Hille is wonderfully acute as Klytemnestra in the early scenes—intense, sharp-eyed, and wholly believable as a caring and patient mom and a loyal political wife determined to support her husband though she doesn’t share his religious beliefs. Her clash with Agamemnon after learning of his plans to sacrifice Iphigenia is the show’s best scene—gripping because of the conviction and realism of her pleas: “The signs aren’t real – Agamemnon . . . it’s in your head, there isn’t any evidence”; “this is about us, this is about a person who came from us . . . what you are / destroying is us, doing something that will overwhelm our history, a single action which if you bring it down on us will obliterate the whole story which precedes it.”

Once this marital argument is over, however, we’re meant to accept that Klytemnestra just gives up, overcomes her panic, and drops her threat to wake the whole house, grab Iphigenia, and run. Moments after the creepy execution, she even offers him grudging admiration, saying his act is “so mercilessly brave”! Come on!! That’s up there with land-sharks and the moonshot hoax for sheer, instantaneous incredibility. The independent-minded, devoted mother played by Hille, who is clearly educated and heads a Western household, would flee Agamemnon instantly and take a bullet for her child. Or else she’d remain fiercely defiant.

PC: Joan Marcus

Eventually, Icke seems to give up on his efforts at psychological plausibility anyway. By the second hour the show is sputtering and slogging through sloughs of airy rhetoric and hortatory abstraction untethered from understandable character development or connection. A character played by Kirsty Rider called Doctor (I had to check the program to find that out) traipses through the play in a black dress, chatting standoffishly with an emotionally disturbed, adult Orestes as if she were his therapist or personal philosopher. She’s clearly no help to him in any case, rattling on weightlessly and pretentiously about things like the confusing state of the world (“Not quite order, but not chaos”) and the relativism of truth. The play’s last act, the trial scene, amounts to a numbing continuation of this Doctor’s bloviation: principally endless strings of ponderous issues (everything from gender to truth to sanctioned violence to justice) trotted out monotonously to an unseen judge in a spirit of deadly administrative bothsidesism.

Very few Americans have ever seen a good production of Aeschylus’s Oresteia. The work is seldom produced not only because it’s so ancient, long and difficult but also because its gender politics are now controversial. Why, really, should Orestes get off just because he’s male? Some theater artists have altered the ending, but Ariane Mnouchkine famously came up with a fascinating feminist approach to the trilogy in 1990 by combining it with Euripides’s Iphigenia at Aulis in her landmark Les Atrides. The combination tilted audience sympathy toward Klytemnestra by starting the saga with her betrayal rather than (as in Aeschylus) her vindictive rage. Icke too has combined the material in these 2 works, but in a completely different way.

Aeschylus and Euripides are very different writers. One is a poet of obscure imagery and dense symbolism whose characters retain a monolithic grandeur, and the other is the father of psychological realism and hence a hero to many moderns. Mnouchkine’s Les Atrides essentially “Aeschylized” Euripides by using Asian theatrical techniques to infuse his work with thrilling performative effects and nudge the whole multi-part production toward the broadly symbolic. Icke has done the opposite in his Oresteia, essentially “Euripidizing” the Aeschylus material by reimagining it as wholly realistic and contemporary. Another adaptor might have seen that such an ancient story needed major adjustment to fit its new, modern environment—as, say, Eugene O’Neill recognized in his Civil War-era Mourning Becomes Electra. Icke evidently saw no such need, and that’s why, to anyone familiar with them, his show feels so much like a diminishment of its venerated sources.

after Aeschylus

adapted and directed by Robert Icke

Park Avenue Armory

This article was first published by Theatre Matters on Aug 10, 2022, and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Jonathan Kalb.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.