The fear and loathing of fat is such a ubiquitous part of contemporary Western culture that it seems inconceivable that a fat person could experience anything other than self-hatred and the desperate desire to be thin. Being fat is synonymous with being ugly, lazy, greedy, diseased, ignorant, stupid, slothful, gluttonous, weak-willed, and unable to resist temptation; fatness is seen as the most heinous sin of the flesh.

Fat studies scholars and activists have worked to challenge these constructions, and counter-narratives are increasingly making their way into mainstream media. The mainstream conversation, however, continues to center normative ideas about health, beauty, and self-esteem, and turns on the question of whether these ideas can–or should–be “broadened” (ha!) to include fat people; they rarely consider fat people’s own perceptions or lived experiences.

Nothing To Lose, the latest piece of work from acclaimed Australian dance theatre company Force Majeure, features a cast of dancers who all identify as fat or bigger-bodied, and moves beyond these “easy ports of call” to explore the fat body on its own terms.

Anastasia Zaravinos. Toby Burrows

The show is a collaboration between director Kate Champion and artistic associate Kelli Jean Drinkwater. Champion established Force Majeure in 2002; Nothing To Lose is her final piece as artistic director of the company. Drinkwater is a fat activist, artist, and filmmaker; her film Aquaporko! has screened at film festivals across the world.

In the program notes, Champion explains she has always been drawn to dancers who move in ways that express some part of themselves and their experience. She goes on to add:

As much as I admire great technical skill in dancers I’m usually more captivated by a physicality and a presence that lives outside society’s general perception of so-called “perfection.”

In Nothing To Lose, Champion was interested in working with the “sculptural quality of the larger physical form,” and exploring the sorts of movement that are specific to fat bodies. Rather than “imposing a pre-formed dance language onto fat bodies,” she worked with the cast to “co-devise a movement vocabulary […] that is genuinely custom made to their body type.”

Julian Crotti. Kate Blackmore

This is part of what makes Nothing To Lose such a unique and challenging piece–it explores not only fat people’s stories but the fleshy materiality of their bodies.

It is this materiality–the living, breathing, solid, yielding, stretch-marked, cellulite-d, jiggling, wiggling, chaffing, consuming, metabolising, sweating, secreting, excreting, materiality of the fat body–that is so often absent from the conversations about self-esteem, beauty, and even health (which is typically judged on metrics such as BMI, rather than an individual’s experience of their own bodies, of pain and pleasure and vitality).

This is not to dismiss those conversations entirely; normative ideas about health, beauty, and self-esteem have very real implications for material bodies, after all. They create a culture in which fat people’s very right to exist is contingent on whether or not we can approximate normative ideas closely enough to be deemed acceptable by the mainstream.

Latai Taumoepeau. Kate Blackmore

But even then, such acceptance is always contingent; never full membership, this is a visitor’s pass a best. (Just look at the inevitable fat-phobic sentiments that will be expressed in the comments on this article if you need more evidence.)

It’s also important that the desire to “overcome” fat-phobic culture doesn’t lead us to ignore or deny the consequences of living in a culture where fat people are tortured for mass entertainment and governments enact policies designed to reduce the number of people who look like us.

Fatness is also banished from public life in ways that are far less obvious. The absence of fat bodies from the stage is a powerful form of erasure. The fact that this is unremarkable only makes it more insidious, contributing to the many ways that fat bodies are prohibited from accessing certain spaces and certain ways of being.

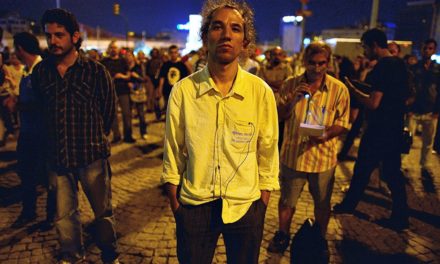

Michael Cutrupi. Toby Burrows

Champion says that her motivation for creating Nothing To Lose was artistic rather than political, but she also acknowledges that this absence makes putting fat bodies on stage inherently political. It’s worth pointing out that the choice not to put fat bodies on stage is also political–it’s just not as obvious because it upholds the status quo.

Nothing To Lose holds onto this tension between the artistic and the political (as if the two were ever entirely separable), which allows an open interpretation.

It’s not about how fat bodies can be beautiful, although there are many moments of beauty. It’s not about how fat bodies can be athletic, graceful, or powerful, although there are many moments of athleticism, grace, and power. It’s not about how anybody can be a “dancer’s body,” although these bodies can certainly dance.

Rather, Nothing To Lose invites the audience to engage with the richness, nuance, and variety of fat bodies and fat experiences in a much deeper and–spoiler alert–more tactile way than they might otherwise.

The result is deeply humanizing and therefore profoundly challenging to normative understandings of fatness. It opens up new possibilities not only for perceiving fat bodies but for living them–on our own terms.

This article first appeared on The Conversation on March 10, 2015, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Jackie Wykes and Cat Pausé.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.