Beauty And The Beast is the quintessential story of a young beautiful daughter who has to live with a wealthy and ugly monster because of her father’s misfortunes. In the end, she learns to put up with the strange creature and even marries him.

It is a universal fable with much potential for each generation of creative thinkers to delve into current societal issues and the meaning and course of human existence. This year at the Adelaide Festival, the American theatre company One of Us productions and the UK-based Improbable have teamed up to present their own version of Beauty And The Beast.

Beauty and the Beast for Everyone

Since the middle of the 18th century, when the famous fairy tale first appeared in the creative output of Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont, Beauty And The Beast has been subject to the analysis that numerous artists have underscored in written and performed texts.

A historical contextualization of the original highlights the rise of the bourgeoisie in 18th-century Europe. Freudian readings of Beauty reference the Oedipal complex–Beauty is holding onto her childhood attachment to her father oblivious of her own sexuality.

The Jungian construction points at personality integration through recognition of the dangerous and forbidden desires that are represented in the story through the metaphor of marriage.

The devised performance text at the Adelaide Festival promises to highlight concerns related to disability and societal taboos but falls short of a world-class standard. It remains at the level of naïve storytelling thanks to the second-rate exploitation of nudity and sex.

It does not do justice to the famous original text and its psychological undercurrents, nor does it capitalize on the important subject of disability and possible critique of the hypersexualized female as a passive object of desire in contemporary media.

A Love Story

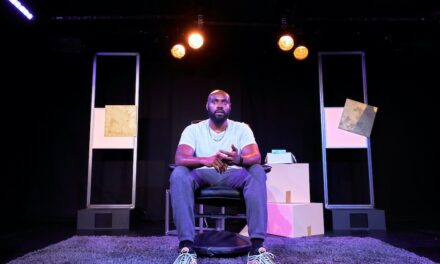

Beauty And The Beast. Sheila Burnett, Adelaide Festival of Arts

The narrative centers on the love story of the two main characters: American burlesque performer Julie Atlas Muz/Beauty and her husband English actor Mat Fraser/The Beast by attempting to provide a parallel to the original fairy tale.

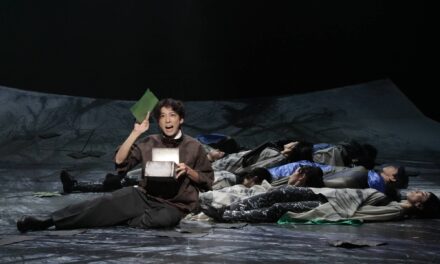

Consecutive vignettes sway between the original story and cabaret-style personal memories of the two performers. It is a burlesque show combined with puppetry and shadow play, impressive costumes, good lighting and set design, underscored by a compilation soundtrack of poor substance and quality.

The supporting couple of puppeteers/assistants/angels Jonny Dixon and Jess Mabel Jones upstage the main pair with their superior acting and movement skills. The use of old theatrical techniques such as shadow play in the first scene and the commedia dell’arte scene of the father and two sisters are very effective.

The show has been advertised as a “sexual journey;” nudity and explicit sexual scenes define it. They are presented with utmost honesty thanks due to the ability of Muz and Fraser to appear totally uninhibited on stage. Muz has a beautiful voluptuous body and can wiggle her derrière to perfection. His body is expressively athletic.

But the nudity in this show is cheapened. It ends up being a means to an end because the narrative is unclear. The emotional charge is shallow and rhythmic shifts and accelerations are left unexplored.

On the night, the audience seemed ready to laugh from the very beginning. They were engaged throughout the entire show. Some even said that it was therapeutic to see such liberal display of nudity. I remained unimpressed and unconvinced by drooping and shaking genitalia, and by the faked intercourse in the last scene.

After all, such spectacles are accessible in many forms and through various platforms today. The cathartic experience I was anticipating did not transpire.

It is disappointing that a show of such poor theatrical merits has been admitted to the Adelaide Festival and that patrons are paying top dollar for something they can see at the Fringe Festival, at the Cabaret Fringe Festival, in the Garden of the Unearthly Delights, or in a Spiegeltent where such entertainments belong.

This article first appeared on The Conversation on March 12, 2015, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Daniela Kaleva.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.