On May 8, 2022, Nigerian-American artist Okwui Okpokwasili’s Bronx Gothic (2014) at Kunstenfestivaldesarts did not end. It didn’t end because not only its story rides on the perpetual logic of dreams and sea waves, but also because this time it skipped a few beats from its climax and denouement—more on this and the new iteration of the show by Paris-based Kenyan artist Wanjiru Kamuyu later.

What you need to know first is that the unending quality of Bronx Gothic is already embedded in its performance history. Okpokwasili toured the performance widely and produced a documentary (2017, dir. Andrew Rossi) around it at the same time, which shows glimpses of her process, personal memories feeding into the piece, as well as how the performance catalyzed conversations in various communities of color around growing up as a most dispensable thing in the United States. The piece garnered attention from the international scene, thus Okpokwasili kept being asked to return to this material, although she created equally powerful yet formally different works after Bronx Gothic. These notably include Poor People’s TV Room (2017) and Sitting on a Man’s Head (2020), again in collaboration with director and designer Peter Born, as her Bessie Award-winner solo. The latter holds an uncanny value for me as a participatory choral where waves of sentences and utterances are shared between bodies, which happened to be the last piece I saw before COVID-19 shot all theatres in the world. I will always consider it as a talisman Okpokwasili wanted her participants to keep in order to endure what would come next.

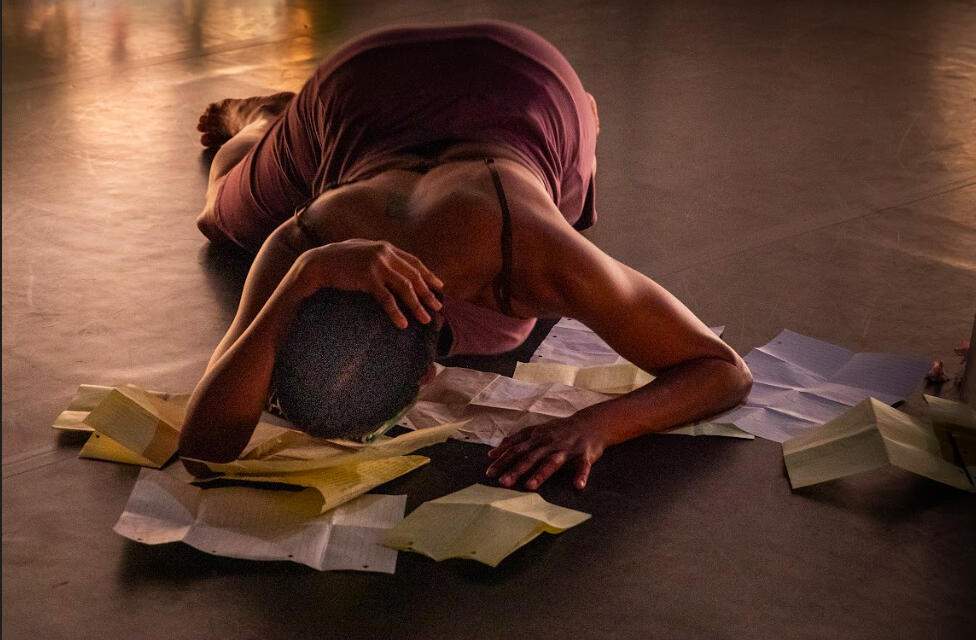

Okpokwasili does have that deeply charismatic presence that I could not attribute to anyone but an oracle, yet she is equally reserved and forthcoming. Bronx Gothic at KFDA 2022, with Wanjiru Kamuyu adopting the solo, is an outcome of this artistic modesty. How else one could transmit a solo to another performer, one that is so physically and emotionally linked? Okpokwasili dares to disentangle from her performative persona this complex and painful story, which is an account of two girls’ opening up to a premature—even traumatic—sexuality with the backdrop of internalized racism and limited access to autonomy. The first-person narrative gives glimpses of the relationship via exchanged notes between the two girls, “one of which was me,” as Kamuyu announces. They express a love that is too illicitly queer to be cherished, and a seething hate that is as much turned to the self as directed to the confining world of deprivation and neglect. It sounds like the narrator was the underdog of this friendship, but had slightly more power in her enough to direct her own psyche. Whereas her friend, rough and dangerously precocious, was suffering from a recurring nightmare, with visceral images that convey a hint of abuse. As the piece proceeds, the voices we hear and the characters they belong to get increasingly interlaced; the narrator with her past self and present confession, and her childhood friend with her riled-up pain and longing for love keep bleeding into one another. True to form, Bronx Gothic never unveils the full view of horror. The audience peers through the slivers of memory and trance, during which the narrator’s quest for truth only drowns her deep into her own affective ambiguity and disintegration.

Ever since I saw it in 2015 in New York Live Arts, I consider Bronx Gothic a masterpiece in how it materializes the trauma temporality—one in which the pieces of mind never cohere, certain details keep pricking one’s eye while others always escape to the peripheral vision, and nothing arrives at a conclusion or a further-beyond.[1] The past becomes a prison in the present, and returning to the shaking and breaking body may only offer a paradoxical, fleeting refuge. Kamuyu rises up to the challenge of bringing this embodiment to life under the antiquated walls of the towering chapel of Les Brigittines. Like Okpokwasili, Kamuyu has her performative signature in dance, song, and spoken poetry and established herself in the New York scene, which makes her an organic choice for this transmission. And yet, as much as the choreo-dramaturgy of Bronx Gothic is so compelling, it has been Okpokwasili’s playful ease at drawing in the audience to desire for more of the story and of the Black virtuosity in delivering it, with no qualms about betraying their anticipation as well as her own authorial presence. Kamuyu is too respectful and loyal to the story, perhaps inevitably so as the inheritor of the material, for such a proverbial dance between voyeuristic spectatorship and performing authenticity.

Distinct from ‘re-performances,’ such performance transmissions are processes where the owner and original performer of a piece intensely works with another artist to get them to embody its heart and soul anew. These are still rare in the field of dance and expanded choreography. One memorable example is Ruth Childs’ 2014 performance of La Ribot’s Más Distinguidas (1997), an iconic solo that depends so much on La Ribot’s body, timing, sense of humor, and flair; another one is the transmission of Pina Bausch’s The Rite of Spring (1975) to dancers from 14 African countries facilitated by Tanztheater Wuppertal veterans Josephine Ann Endicott and Jorge Puerta Armenta at École des Sables in Senegal in 2020. These are cases where the transmission is completed with recognizable success and new discoveries about the works, while there may have been many more that somehow failed and did not surface to the public. The sustainability of a performance, if you will, is still an essential question for choreography or any other embodied practice, especially ones that demand so much from the whole being of the performer, for continuing beyond the originator’s circumstances and lifetime.

Kamuyu’s interpretation honors Okpokwasili’s original while seeking her own attitude within it. Yet it sometimes gets subdued by Kamuyu’s reverent temper, who unlike her predecessor explores how anger and yearning might implode. Where Okpokwasili let the characters detach and shatter like the shards of a mirror, Kamuyu prefers to underline the futile and stressful effort of holding it together. There is no denying that Kamuyu has a different physicality and voice, and it seems like the artists made a deliberate choice to integrate this as a shift in tonality. Kamuyu’s performance style makes it easier to trace and lock the unreliable narrator to the more naïve girl who speaks in a childlike voice. But is this really what the story needs? While Kamuyu’s strength and dedication to the performance are quite palpable, Bronx Gothic is a test of physical storytelling, the sheer force of which seems to have overwhelmed Kamuyu in the latter half. This might have been a result of the technical difficulties in the sound-mic department, yet the peaks and valleys of energy that Okpokwasili deftly rode through get more subtle and somewhat flatter with Kamuyu’s choices. That said, Okpokwasili has mastered the art of alchemizing lies and fake emotions into powerful physical states such as wailing during her years as Ralph Lemon’s collaborator.[2] It could just as well be that Kamuyu associates neither with this choreographic hyperbole nor with the gothic genre’s use of the florid, thus has erred against mimicking either. She may be better for it, but that is probably why Bronx Gothic exhausted Kamuyu as well as its Brussels audience without a clear end.

[1] I have written on this earlier in “Peripheral Vision: Review of Okwui Okpokwasili’s Dance Performance Bronx Gothic,” GC Advocate 27 (3), 2015, https://gcadvocate.com/2015/12/23/1978/.

[2] Ralph Lemon’s dramaturg Katherine Profeta elaborates on the tactical uses of unreliable narrator and performative mourning in her book Dramaturgy in Motion: At Work on Dance and Movement Performance (Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2015).

This article originally appeared on Etcetera on May 23, 2022, and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, please click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Eylül Fidan Akıncı.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.