As London celebratess the 50th anniversary of the Pride Parade on July 2, I’m reminded of the only play in London I’ve seen that has an asexual (or “ace”) main character: The Slug Show.

Premiered in September 2021 at Camden People’s Theatre’s Sprint Festival, The Slug Show is a solo tragicomedy and Bildungsroman created by The GOO, including playwright Jiaxi Wang and actor Maki Omori (both non-binary and autistic), and director Yifan Wu (queer). The performance focuses on the character Slug, who sluggishly navigates their life at the intersection of autism, queerness, and immigration in London. The show opens with Slug carrying a large suitcase on stage, explaining to the audience that they just broke up with their partner (who is also non-binary) and is moving out. As they waits for the train at the station, Slug takes out numerous daily objects, personal items, and souvenirs from the suitcase, each representing a short story of their life to be told. Some of the stories are humorous and immediately relatable, such as jokes about poor life choices of majoring in theatre, being awkward with making small talks at the cafeteria, and trying to act like an adult in the professional world. Some stories are more personal and vulnerable, such as being told they doesn’t look autistic enough by the GP doctor, struggling with a polyamorous yet uneven relationship, and dealing with the recent suicide of a close friend.

I describe the play as a meta-performative, for it constantly examines the question of the performativity of acting: acting a character on stage, acting a role in society, and above all, acting “normal.” We humans are mimetic animals. Since infanthood, we learn how to speak and how to behave through imitation, and these languages and codes we learn after are so naturalized that we cease to question them. The norm is what’s invisible. However, Slug makes the norm strange, and through the eyes of this asexual, autistic, Asian person in London, the norm becomes visible everywhere, along with its constructedness and arbitrariness. While these codes of normality often present as obstacles and impossible standards in Slug’s daily life, Slug responds to them with a playful attitude, looking at them from a little distance with a critical sense of absurdity, as well as good-humored curiosity.

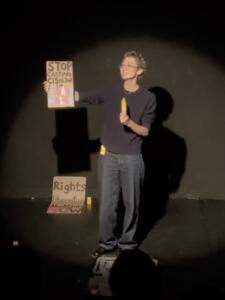

Slug protesting misrepresentation in casting (actor: Maki Omori; photo provided by Jiaxi Wang).

Other than the normality constructed by the majority, The Slug Show also engages with the mainstream media representations of minoritarian groups and their consequences. Slug recounts a day when they and their partner realized that tomorrow was going to be the Pride Parade, which neither of them intended to go. While the Pride Parade has become the very icon of diversity and inclusiveness, with so many colors represented on the many flags, it seems a quite homogenous and exclusive event to Slug, who didn’t feel their kind of queerness could fit in. Slug then compares the Pride Parade with the Stop Asian Hate parade, which are both group performances of some codified political expressions that are uneasy to them. The emotional tension of the play reaches its highest point when Slug embodies an aggressive, outspoken activist at an imaginary parade, where they gave a speech against the casting of autistic and trans characters by abled, cis actors, as well as the gender, racial and classist prejudice in the casting of these roles. Besides the speech’s message, what is highlighted is the difficulty of the very act of speaking. In fact, the speech ends in a self-questioning, as Slug inquires the audience: “Was that okay? Should I make my voice, I don’t know, more confident? More assertive?” Slug’s powerful speech is simultaneously complicated by the fact the real Slug would never be present at such public events, let alone speak in front of all the people, due to autism, cultural difference, and language among other reasons. While the message is important, the performance of the speech more importantly draws our attention to the absent and the unseen, who remain absent and unseen in the “democratic and egalitarian” society.

As such, instead of the ready-made labels of racial, sexual, and disability identities, Slug chooses to create their own identity: a slug. Slugs are small, quiet, soft, and ambiguous. They lack a defined shape and are apparently hermaphrodites from birth. Slugs are vulnerable but brave; they live bare without a shell to hide in. As Pride Parade and Stop Asian Hate parade occupies the streets, Slug playfully and proudly imagines a Slug Parade. To this date, representation of asexuality is still rare and often defined in terms of a “lacking,” like a disability. Representation of autism either suffers the same prejudice or is fetishizingly romanticized. The Slug Show does not focus on the Otherness of the character. Rather, a narrative told by, about and performed by queer autistic people, it creates a space where the normal becomes less normal and the different becomes more relatable. Here, Slug is portrayed as different but same, same but different—just like everyone in this world. The convincingness of the play is equally contributed to the honest and sophisticated writing by Jiaxi Wang, the simple yet effective story-telling by director Yifan Wu, and actor Maki Omori. With their nuanced and easy-going, unique and persuasive stage presence, Omori took command of the energy on stage and made the character alive. Deals with sensitive and poignant personal stories with the lightness of laughter and the gravity of love: love for life, love for connections, love for creativity, and love for hope in the goodness of people.

The Slug Show

Camden People’s Theatre

Writer: Jiaxi Wang

Dramaturg & Director: Yifan Wu

Associate Director: Tianxin Tian

Sound: Jamie Lu

Cast: Maki Omori (Slug)

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Yizhou Zhang.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.