On a recent Sunday afternoon, at the New Victory Theater, timelines collided. The New Vic, founded in 1900, is the oldest operating theater in New York City, but the play I was there to see, Ajijaak On Turtle Island, tells a story that is centuries older. And the whole performance was geared towards an audience that hadn’t been born before 2010. And it got more complicated yet. “Ajijaak” is the Ojibwe word for a whooping crane, and the play imagines a world in which figures from First Nations mythology coexist with contemporary ecological concerns and an urban landscape.

Ajijaak On Turtle Island, written by Ty Defoe (Oneida/Ojibwe Nations) and co-directed by himself and Heather Henson and featuring puppets from the Jim Henson Creature Shop, represents the first time in its century-plus of existence that the New Vic has presented a story from an Indigenous perspective. And what’s more, Ajijaak presents multiple Indigenous perspectives and traditions all at once. Diversity is woven into every aspect of this show, from the range of musical styles to the variety of puppetry techniques.

But most importantly, many of the performers are members of Tribal Nations. Some of the performers chose to list their ancestry in the program, which insists that heritage is as important to these dancers, singers, and puppeteers as any professional training. The musicians John Scott-Richardson (Saponi/Nansmond and Tuscarora) and Kevin Tarrant (Ho-Chunk and Hopi) sat in an opera box, from which their drumming and singing poured down over the stage and audience. Company members also provided choreography and technical consulting, representing traditions that include Echota Cherokee, Cheyenne River Sioux, Kuna, and more. In fact, before the show even began, a theater staff member took the stage to acknowledge and thank the original inhabitants of this land: the Lenape, the Merrick, the Carnarsie, the Rockaway, and the Matinecock. It wasn’t just priming us for this show, either; a plaque inside the theater delivers the same message.

Heather Henson does not boast any tribal affiliation, but her father, the magical Jim Henson, created a tradition of puppetry and story-telling that is upheld by all five of his children. Her company IBEX Puppetry produced this show, and the way her work honors simultaneously the environment and her father’s legacy resonates beautifully with the story of Ajijaak.

Ajijaak is a coming-of-age story and a hero’s journey of a baby crane. Right before the cranes’ annual migration south, the hatchling Ajijaak is separated from her parents. She must travel alone along across what is today called North American, a landmass many Native American tribes knew as Turtle Island. Look at your map, now turn it so south is on the top – Mexico is the turtle’s head, Florida and the Baja peninsula are its front legs, Newfoundland and Alaska are its hind legs. In the play, this reorientation was led by Joan Henry (Tsalagi/’Nde/Arawaka), who plays a grandmotherly narrator.

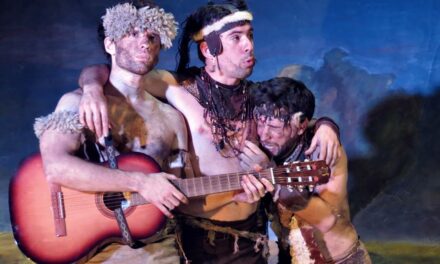

Photo by Richard Termine

A talented puppeteer and singer, Henry is above all a storyteller, and this is her role both in the world of the play and on the stage. Her strong connection with baby Ajijaak was redoubled by the children in the audience, whom she absolutely captivated. Early on in the show, before their separation, Ajijaak’s parents teach her a song. It’s called Ho Ho Watanay and it’s based on a Haudenosaunee song. The song is Ajijaak’s inheritance and her strength. Henry and Henu Josephine Tarrant (Rappahanock, Ho-Chunk, Kuna, and Hopi), who performs as Ajijaak, then teach it to the audience. They lead a rousing sing-along and the fact that the lyrics are in Haudenosaunee stopped absolutely no one from joining in. After all, children are far less self-conscious than adults about enthusiastic audience participation. Henry promises that later on, Ajijaak will need our help to sing it. When that moment came, the children sang as if Ajijaak’s life depended on it, because it did. I sang too, betraying an earnestness I hadn’t felt since Peter Pan instructed me to clap so Tink knew I believed.

On her journey, Ajijaak meets a secession of allies, each of a different species and style of puppetry, each with something to teach her. Birch trees become a graceful deer, a series of hoops shake and jangle with blue crabs, a sly coyote jumps excitedly like a family dog at the park. My favorite was the shaggy, snorting bison. Performers held the bison face-masks over their chests, while their own heads became the beasts’ broad shoulders. (Bison are always my favorite: wise and calm but not to be messed with.) She’s destined for a confrontation with Mishibizhiw, the giant horned aquatic panther whom ecological destruction summons, angry, from her watery home. When Mishibizhiw appears onstage, it’s reminiscent of Chinese dragon dance. Multiple strong and elegant puppeteers are needed to manipulate this creature, which is no less beautiful for being fearsome.

Photo by Richard Termine

Ajijaak also grows, maturing physically as well as emotionally, on her journey, and the cranes alone brought together many different methods of puppet-work. Marionettes walked, kites flew through the crowd, projections created the impression of an entire swoop (yes, that is the collective word for a group of cranes, you’re welcome), a massive crane puppet the size of a sailboat spreads its wings, only to cradle the same egg Ajijaak hatched out of at the top of the show. The show’s finale is a spectacular display of technical virtuosity and a reminder that every stage of life is but a temporary one.

The little boy, three or so, sitting to my right, didn’t fully grasp that. “Where’s Ajijaak?!” he not-quite-whispered to his dad. The symbolism may have been there for the grown-ups, but the kids were fully thrilled by the story. And although the little boy didn’t understand right away that baby Ajijaak had grown into an adult, the same way he can’t imagine how he will someday do the same, yet he was passionately invested in the story. He was relieved when his dad told him that Ajijaak was right there – safe, strong and now indelible in these children’s imagination.

Woke parenting notwithstanding, most of the kids in the audience probably didn’t realize how revolutionary Ajijaak On Turtle Island was. For them, it was just a fun puppet show, just like when I was a kid, The Lorax was just a fun book. And yet, The Lorax taught me to “speak for the trees, for the trees have no tongues,” a refrain still deep in my heart that reminds me to contribute to Earth’s upkeep. I know Ajijaak will have the same effect on these kids, because on my way out of the theater, I heard a little girl absolutely belting Ho Ho Watanay.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Abigail Weil.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.