In 2007, visual artist Jewyo Rhii and curator Hyunjin Kim held an unusual exhibition titled Ten Years, Please, in which some visitors took one of Rhii’s pieces home with them. Rhii’s work often entailed international travel, and she couldn’t afford long-term storage for her ever-growing collection of sculptures and installations at the time. As a temporary solution, they asked willing participants to hold on to one of the objects for a decade. After that term, the artist would reclaim custody. Ten Years, Please wasn’t an auction, it was an orphanage program. The appointed “guardians” signed contracts agreeing to take care of the adopted pieces, described lovingly in Rhii’s own hand in the paperwork.

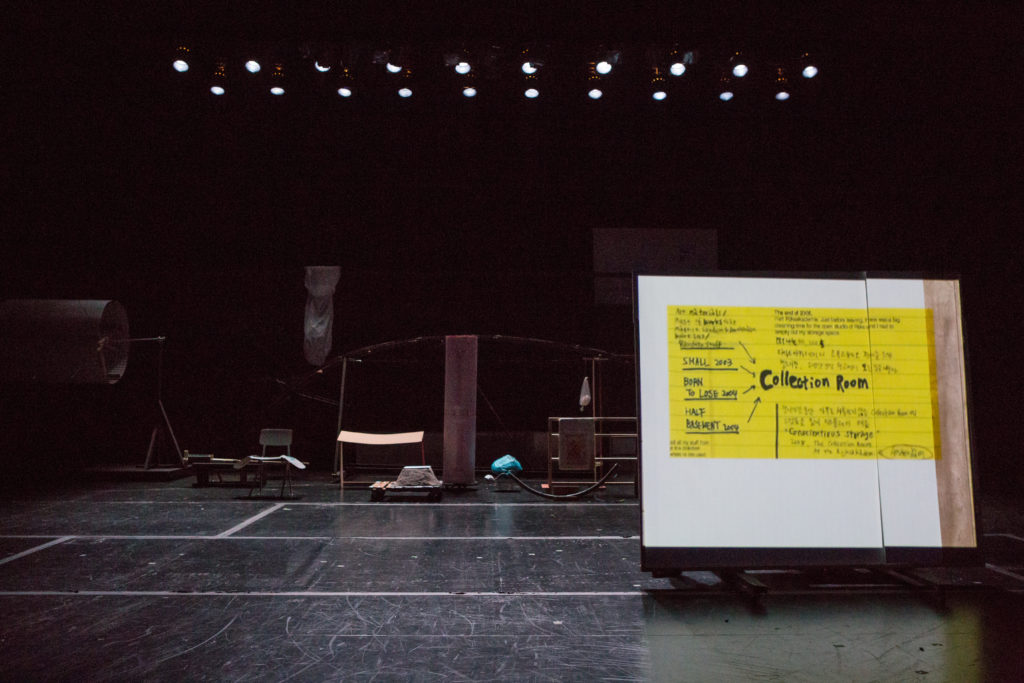

Those ten years have passed. Curatorial Lab Seoul, founded by Kim, has created an object-oriented performance, also titled Ten Years, Please, as the culmination of the ten-year experiment in a co-production with Namsan Arts Center. As Kim writes in the program notes, Rhii’s sculptures “are the main characters onstage,” telling stories of their creation, dispersal, and reunion. She also notes that they chose to present their outcome through theatre rather than an art exhibition because they believed that the artworks would feel more alive in a 70-minute performance than if the objects were simply sitting in a gallery for eight hours a day over several weeks. After all, the project began as a way to extend their futures, to give them a shot at a new life after ten years in hibernation.

Ten Years, Please by Jewyo Rhii & Hyunjin Kim. Photo courtesy of Namsan Arts Center, Seoul Foundation for Arts and Culture. (c) Cho Hyun-woo.

The audience gazes at Rhii’s sculptures throughout the performance, brought in and out by expressionless stage crew wearing black. Sometimes the humans onstage operate a moving component or wrap one of the floppy pieces around their bodies, but they take care not to draw attention to themselves. Rhii’s recorded monologues play over some of these prolonged encounters between the objects and the audience, describing how the pieces were made, as well as her anxieties about art’s continued life beyond the artist’s reach. Some of the monologues, still voiced by Rhii, take the object’s perspective. “I’m sorry I asked you to come see me,” mumbles a work titled Today On The Floor, a stained cardboard rectangle. Would it have stood up and bowed apologetically if it could move? Or is it lying flat on the floor because it is sorry?

Later, we see a filmed interview of one of the guardians who apparently had forgotten about the object that he adopted. (It had been sitting in a corner of his office this whole time.) Another interviewed custodian asks, “Are you taking it? Finally, I’m free!” Meanwhile, the object onstage looks at their former foster parent.

Ten Years, Please by Jewyo Rhii & Hyunjin Kim. Photo courtesy of Namsan Arts Center, Seoul Foundation for Arts and Culture. (c) Cho Hyun-woo.

Rather than tell a sequential story, the production provides glimpses of the project from many different angles, engulfing audiences in the inevitable tangle of memories, notes, and conversations that arise when you attempt to catch up with someone, or an inanimate object, after a decade. Yet these bits and pieces of narrative are secondary to encountering the objects themselves, their materiality and volume, the space that they occupy.

Setting aside the inventive premise, Ten Years, Please was an engrossing performance because the sculptures were so unique and full of character. Rhii works primarily with salvaged objects and nondurable materials. Her pieces are intentionally fragile and unstable. Shiny Chair, for example, with its legs, seat, and back all askew, looks like it would probably collapse if someone tried to sit on it. Discolored and worn, these objects have the demeanor of survivors that have weathered ten years of neglect. However, not all of them made it. According to the catalog included in the program (an online version of which is available here), Shiny Chair 1 and 2 are classified as “ghosts.” They are new copies, built to replace originals that their guardian, also a sculptor, misplaced while moving into a new studio. The lost chairs represent another aspect of the human-object relationship that Ten Years, Please explores—how we remember and find replacements for beloved possessions that disappear. It’s also fun to imagine the unsittable, iridescent chairs wandering Seoul like a pair of stray cats.

Several of the pieces, including Today On The Floor and another chair sculpture titled Blackhole Chair, are responses to work by Rhii’s colleague Yiso Bahc, who passed away in 2004. Rhii’s recorded monologues dryly explain how she created a new work by adding onto or modifying something that Bahc had previously made without providing any background on her relationship with the influential conceptual artist. Still, the objects began to convey emotion, presenting themselves as concrete proof of their artistic friendship, carrying within them an inter-biography. Rhii’s choice to preserve these pieces by handing them off to strangers takes on additional meaning in that regard. How much emotional real estate do we have, and when is it helpful to pack away some memories so that we may travel lightly?

Ten Years, Please by Jewyo Rhii & Hyunjin Kim. Photo courtesy of Namsan Arts Center, Seoul Foundation for Arts and Culture. (c) Cho Hyun-woo.

Of course, artists and their cumbersome sculptures are not the only ones burdened by the economics of space. Ten Years, Please also works nicely as a contemporary fable about the South Korean housing crisis. Over the past several decades, real estate prices have skyrocketed in Seoul so that many millennials, even those with decent jobs, can’t afford rent prices, let alone buy their own home. Some of them stay with their parents after college, stuck in financial limbo for ten years or more. Others live in tiny flats called goshiwon, little more than storage closets for human beings. The project, with its collection of objects that look like they’ve just come from a junkyard, quietly pushes against a society where people wonder whether they’re worth the floorspace under them.

We never learn whether Rhii has found a permanent home for her scattered children. In an interview with critic Bang Hye-jin, who asks what will happen to the pieces after the production, Rhii says, “I don’t know yet.”

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Kee-Yoon Nahm.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.