“I hate critics!” actor Gerald Langiri bellowed, sparking laughter. But his face remained deadpan. For him, this Theatre Criticism Conversation at the Goethe-Institut in Nairobi, Kenya, was no laughing matter. The conversation, we were informed, was sparked by Langiri who had complained about theatrical in an online article. “What kind of people are these who write criticism?” he wanted to know (But methinks the man doth protest too much.)

Other participants at the discussion included UK-born Keith Pearson, the Creative Director at The Theatre Company; actor/playwright/trainer Aroji Otieno; arts critic Margaretta Swigert-Gacheru; theatre critic Ann Manyara; performers from various troupes and myself–a playwright, poet, and novelist.

Gerald Langiri, a versatile actor who has done a commendable job of uplifting the local acting profession through his platform Actors.co.ke, made it clear that he was “playing the Devil’s Advocate.” In other words, to create a debate atmosphere, he had picked a side–that of opposing the critics. At some point in the discussion, Keith Pearson–who has been involved in “the world of performance” for 45 years–offered to “borrow the Devil’s Advocate hat” from Langiri. “If someone is going to be a critic,” he said. “They must understand the culture.” On the issue of Nairobi being the Mecca of Kenyan theatre, he said: “We tend to be very Nairobi-centric. What else is going on out there (in the country)?” Margaretta Swigert-Gacheru, who now writes for the Business Daily newspaper, agreed that “the level of interest (in theatrical arts) in daily media is not very high.”

In the early going, I argued that the issue of harsh critiques was not unique to Kenya and that many performers, especially in the Western world, have received stinging and sometimes infamous assessments; the kind that led G.B. Shaw, a winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature, to quip: “A theatre critic is a person who leaves no turn unstoned.” I added that unflattering comments are usually honest. An actor who assumes as many roles, and is as experimental, as Gerald Langiri can’t hope to give a stellar performance each time.

Ann Manyara, who has herself been actively involved in theatre, was quite articulate:

“Criticism is being analytical, not criticizing. A critic serves the art…To be a critic, you need to love the art you criticize. When I was beginning, I announced my standard: I love the arts. The object of the critic is to serve a standard…

You need to look at criticism from a cultural perspective. For example, French and US films are different. Nollywood is different. Hollywood is different…

I will not write promotional pieces, as a critic. Also, if I write a critique based on rehearsals (an idea that was popular with newspapers for while), that will not be fair because the actor is still finding his character…A preview would be very good because it is not a rehearsal…When you (the critic) writes, it is assumed that it is about the opening night. Some critics even indicate if their review is not of the opening night…

Choice of words is key. For example, instead of saying the play is shit, say ‘The players tried something abstract but it didn’t come out well.'”

Local theatre companies are so averse to criticism (or misunderstand it so much) that a few have even gone to the extent of banning certain writers from their events! It is a silly thing to do for several reasons: (1) The critic can send an agent to your show (2) Due to the rapidly increasing entertainment options, live theatre needs media coverage more than ever (3) Like death and taxes, there will always be critics. Even if no established journo/blogger attends your show, disappointed audience members can still massacre it on social media. Still, you can’t blame technology for ruining your show. It is merely a tool in the hands of a human being. “The issue of a personal vendetta doesn’t arise,” Ann Manyara emphasized. “I hardly know anyone in the theatre personally…My loyalty is to the art, not the person.”

Keith Pearson also acknowledged the importance of media in the promotion of the arts. “The Internet has changed the rate and pace at which content is reviewed. We did a show in India, for 1500 people, and the next day, ten national newspapers had picked it up.” Gerald Langiri added that, “We (thespians) don’t have private screenings for critics but you can send a press release to the newspaper columns that cover the arts. Most artists don’t know how to write them. They should learn to and them to the media to promote their production.” Ann Manyara shared another media tip:

“Photographs (in the media) are the one thing that can make you look good, even if the review is bad. Most (theatre) companies don’t prioritize the media release. Appoint somebody to handle publicity, preferably not the (show’s) director because he is otherwise creatively involved.”

There is no rational reason for artists to fear/avoid art critics. Invite them to your shows. Get their contacts (which is usually easy enough because they want to be found/invited/updated). Most of them, especially bloggers, are huge fans of the art form they are covering (that’s usually why they are doing it in the first place). Here, for example, is part of what Margaretta had to say concerning Cajetan Boy’s Backlash:

“Phoenix’s professional cast make Backlash one of the most memorable shows I have seen all year.” (Saturday Nation, August 17, 2013)

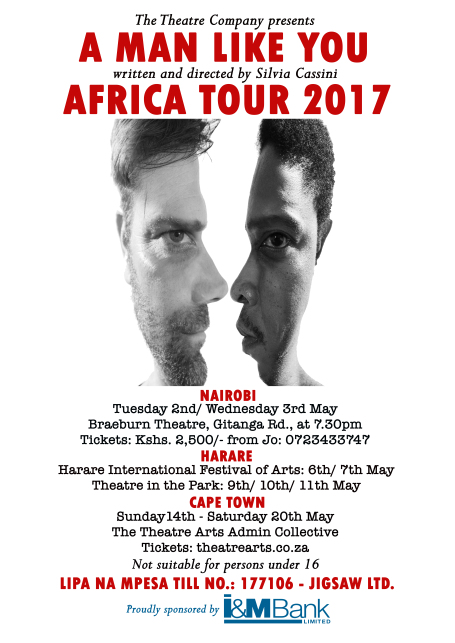

On occasion, Kenyan shows have achieved international success. These include the terrorism thriller A Man Like You, the star-studded musical Mo Faya, and the Swahili version of William Shakespeare’s The Merry Wives of Windsor (Translated by Ogutu Muraya, Wanawake Wa Heri Wa Windsor received 5 stars from The Guardian newspaper when it premiered in London).

The publicity poster for the thriller, A Man Like You

Ann Manyara also touched on intellectuals: “(There exists) a bit of tension between newspaper critics and academic critics,” she said. “Academic critics tend to look down upon the newspaper critics. They can write a 4000-word paper on a particular critic!…The newspaper critics, on the other hand, feel they have ‘the swing,’ they have the people.”

As part of the Theatre Criticism Conversation at the Goethe-Institut, a young male actor named Akuya Ekorot gave a brief solo performance of which all attendees were encouraged to write and send in their critiques. The title of the performance, which had won the 1st Runner-Up Prize in the inaugural Actors Monologue Challenge in 2016, was The Rapist. (An audio clip of it is available online.) The actor stepped into the empty space in the middle of the attendees and began his delivery: “I am a terrible person,” he said, with no shortage of drama. “Let me be more specific for your concern: I am an R-A-P-I-S-T. Rapist. No, this is not another analogy. I am not using metaphorical statements here…I rape people, people in general. It don’t have a specific type…Age to me is just but a number…At least I am honest about it…Look at you hypocrites, portraying that saintly façade, and pretending that you did not play a part in creating this monster I am…Love, my friends, is overrated…I will be your rapist.”

Since we, the audience, were supposed to comment on the piece, here are my sentiments: “Good use of stage, considering that he was performing ‘in the round’…Excellent voice projection…Kept the audience on edge, especially the women, but they laughed uncomfortably at a line about the hate that ensues when one dumps his girlfriend ‘after raping her, of course.'” Conclusion: I didn’t like the subject matter and, as a consequence, I would not recommend the play. I have no problem with edgy material but I personally know women whose lives were destroyed by rapists–one of them as a minor–and, therefore, sexual violation is not something I would like to see being justified anywhere, in any context.

THE ROLE OF CRITICS

The Oxford dictionary describes a critic as “a person who judges the quality of something, especially works of art, literature, and music.” “Critical” is defined as “of or relating to the judgment or analysis of sth, esp literature, art, etc.” This leads us to “critique” (noun) which refers to “a critical analysis,” and therefore “criticism” refers to “the art of making judgments in literature, art, etc.”

In Kenya, we rarely actually use the word “critic;” the term “reviewer” is more often employed. In addition, rarely have pure “theatre critics.” Usually, the reviewers cover a variety of arts: visual arts, performing arts, literature, etc. Theatre critics are also utilized in theatre award processes.

Noted Kenyan theatre critics include Margaretta Swigert-Gacheru (Nation Media Group aka NMG), Faith Oneya (NMG, formerly blogged at LiteraryChronicles.com), George Orido (Standard Media Group), Anthony Njagi (NMG), Ogova Ondego (ArtMatters.info), Oby Obyeodhyambo (who is himself involved in theatre), Kamau Mutunga (NMG), Joseph Ngunjiri (NMG) and Ann Manyara (A member of the International Association of Theatre Critics). Margaretta Gacheru is the longest-standing of these writers, having been covering the arts in Kenya since the 1970’s!

REASONS FOR NEGATIVE CRITICISM

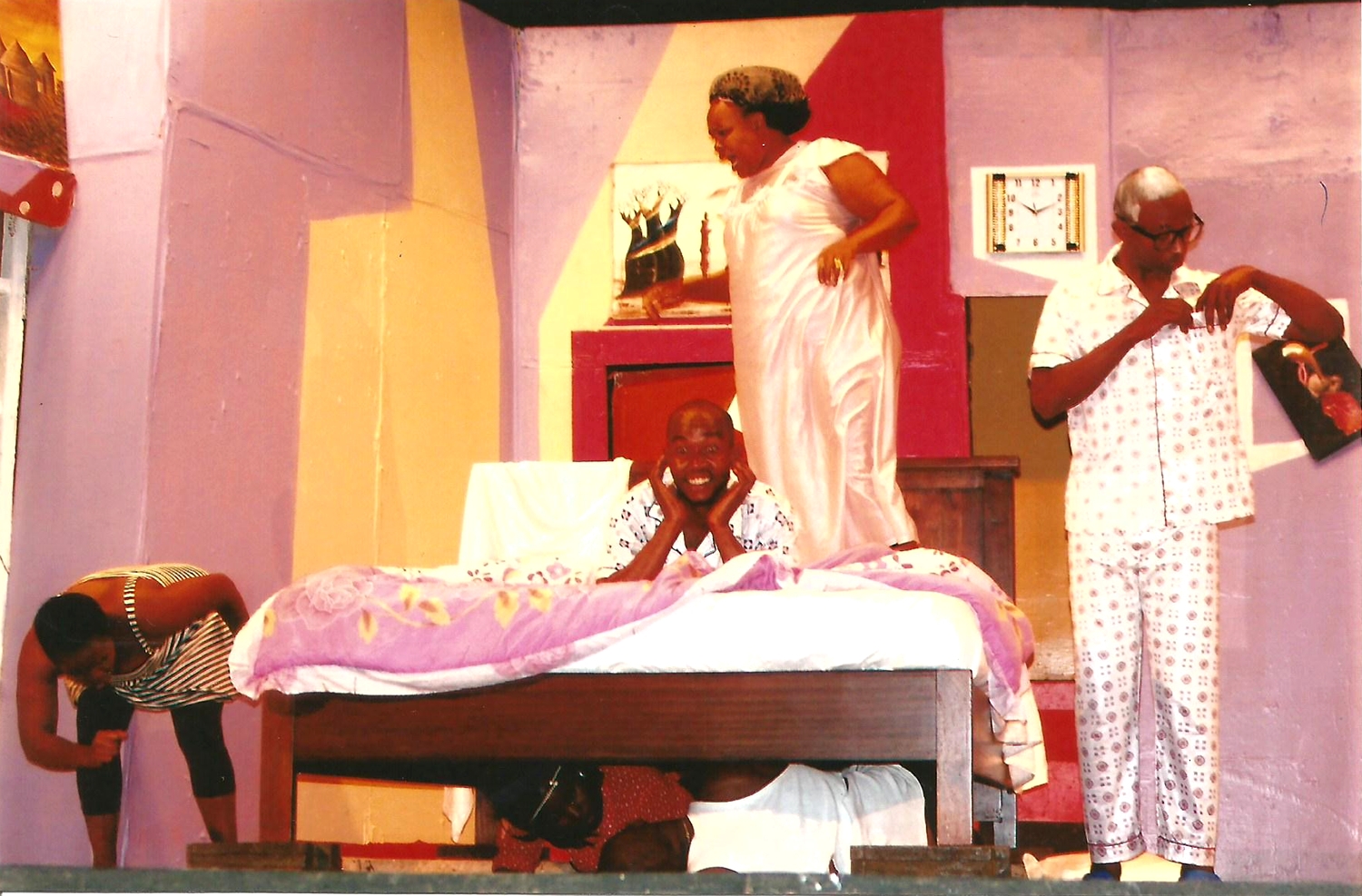

- Obsession With Bedroom Farces aka “Trouser-Loosing Plays”

I love comedies! All kinds of comedy–stand up, roasts, farce, satire, physical, situation, one-liners, etc. I’ve written comedic plays myself–like What’s Wrong With This Picture? and Hannah And The Angel. But too much of one thing breeds contempt. I love chapatis but I don’t want to eat them every day. Variety is the spice of life–something that local theatre groups are yet to grasp. Whether a stage production be in English or vernacular, it is almost always a bedroom farce (and often a foreign one like When Did You Last See Your Trousers? or Birthday Suite.) Think of movies or books–in how many genres do they come? Horror, Thriller, Comedy, Romance, Drama, Historical, etc. I’ll concede that there has been a recent spike in the number of musicals produced but these are, once again, mainly adaptations of foreign material (Kenyan musicals will be covered in a future article here on The Theatre Times.) There are so many topics that local writers and producers could explore–from politics to crime–but for now, you can rest assured that “coming soon to a theatre near you” will be a play in which a character will be caught with his trousers around his ankles!

A Comedy of Errors. Bedroom farces still dominate urban Kenyan theatre. (Photo: Alex Nderitu)

- Endless re-hashing of foreign plays

In a newspaper interview, a former thespian asked why on earth a theatre company would expect him to buy a ticket to watch a play (in this case Boeing Boeing) that he himself “starred in ten years ago.” It is a common lament. The national inter-schools drama competitions–with their over-the-top costumes and pitchy “choral verses”–often display a lot more originality and creativity than the “professional” theatre scene. Below is a Facebook rant by yet another former thespian and scriptwriter (name withheld):

“Dear Kenyan theatre companies…please stop sending me invitations to watch your ‘latest hilarious rib-tickling blockbuster comedy’–Run For Your Wife or Birthday Suite or Bedside Manners. Those are farces written in the 50’s and 60’s for British audiences, which you bastardise by changing character and place names–Kenyanising, you call it. It doesn’t work, and it’s actually illegal! We’re tired of repeats of old British plays! I don’t want to see Boeing Boeing again–it’s outdated! We’re in the age of mobile phones and the internet, two things which would make those plays very unfunny in a second! Stop being lazy and create something original!”

Copyright issues are a hot topic in the entertainment business here, but as Kenya/UK comedian Njambi McGrath once joked, “Trying to explain to people in America where Kenya is, is as frustrating as trying to explain to Africans the concept of copyright.”

I applaud people like Aroji Otieno (Aroji School of Drama) and Walter Sitati (Hearts of Art) for composing their own stage plays, not dramatizing school set-books or pinching material from Samuel French Ltd. As UK actor David Niven noted in his best-selling memoirs, The Moon’s A Balloon, “The word ‘playwright’ is spelled that way for a very good reason. Shipwrights build ships, wheelwrights fashion wheels, and playwrights construct plays.”

- Lack of local/relevant/relatable material

It is said that Emperor Nero “fiddled as Rome burnt.” If this is true, then he must be the patron saint of Kenyan thespians. What happens on stage is often completely divorced from what is going on in the “real world.” For example, 2017 was one of the worst years for the country in general. A drought early in the year led to human and animal starvation in some areas and gov’t subsidization of maize floor. Several industrial strikes, notably by teachers and medical practitioners, crippled the education and health sectors. To make matters worse, bitter political campaigns leading up to a contentious General Election pushed the country to the brink of civil war. As riot police battled protesters in the streets, politicians bickered, the international community called for dialogue, violence erupted in the slums, investor jitters wiped billions of shillings off the Nairobi Stock Exchange, and the economy went into reverse gear, what were thespians staging?–Their beloved farces! Like Nero, they were “fiddling” while the nation burned.

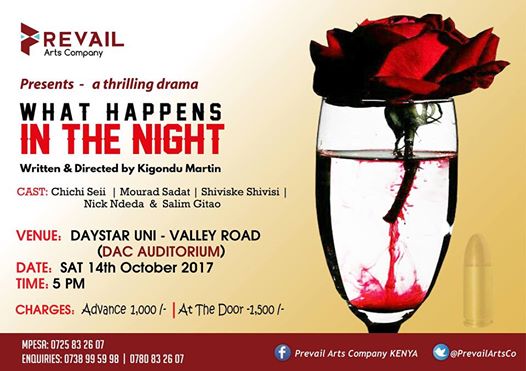

It is only after the nullification of the Presidential Election (in August 2017), and the Supreme Court’s unprecedented call for a fresh election, that politically-themed plays began to appear in the major venues. One such was What Happens In The Night, written and directed by Kigondu Martin. The producers, Prevail Arts Company, described it as a “riveting drama about a prominent family trying to balance their personal baggage with being in the limelight while interrogating the on-goings of Kenya in frustrating times.”

The publicity poster for the play What Happens In The Night (2017)

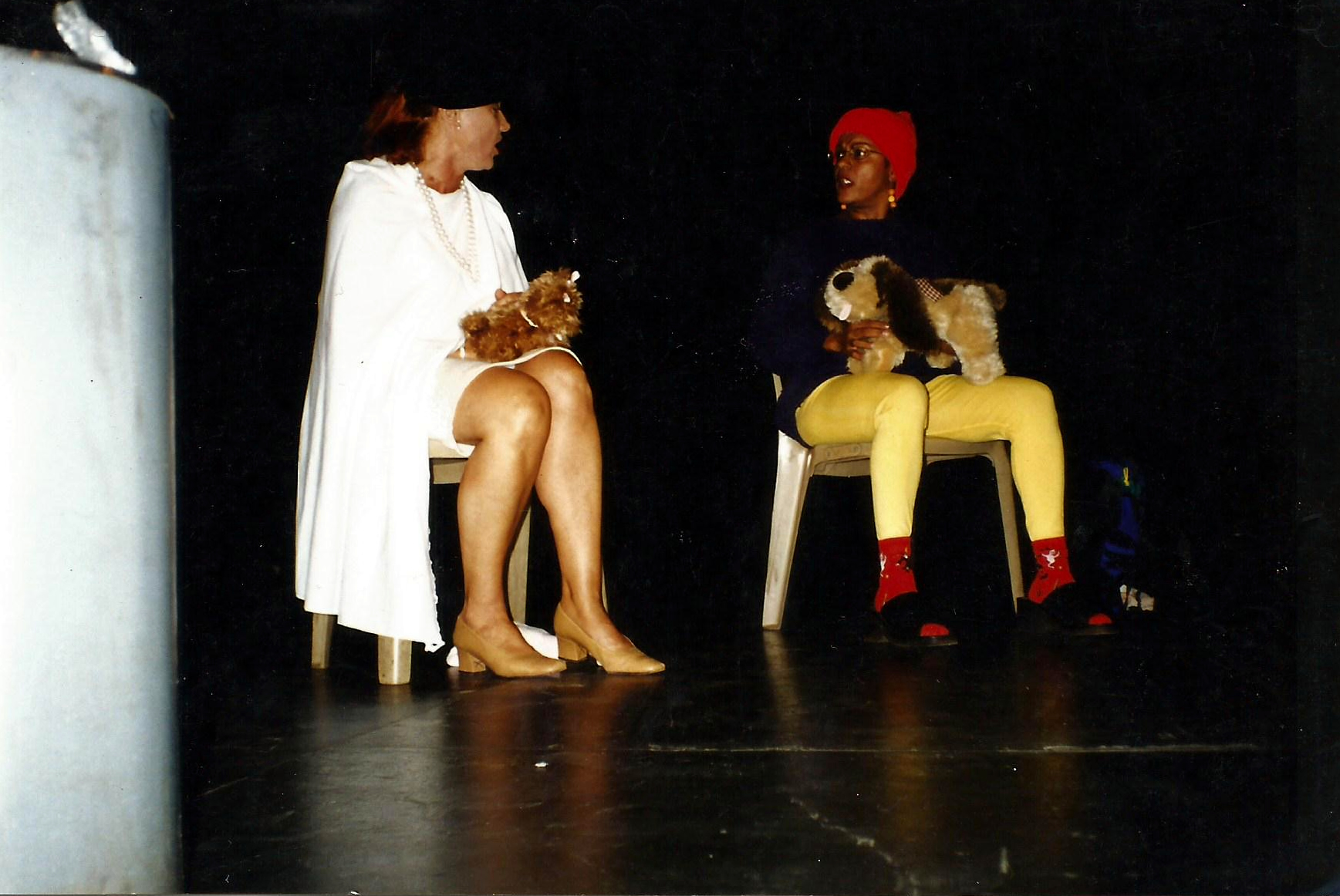

From the past to the present, other entertainment entities have picked up juicy Kenyan stories that the locals take for granted. For instance, there is no major Kenyan play about the man-eaters of Tsavo. The two international movies about the lions that terrorized the Kenya-Uganda railway builders, Bwana Devil and The Ghost And The Darkness, were both Hollywood productions. The latter, which starred Michael Douglas and won an Oscar, was controversially shot in South Africa. And while we can excuse our underdeveloped film industry for not taking up the mantle (a period piece involving wildlife might be too challenging for our filmmakers), there is no good reason why theatre groups can’t re-enact the chilling true-life story. Unlike movies, most theatre productions are minimalist in nature. You want the least amount of fuss–not too many scenes, no superfluous characters, no unnecessary costume changes etc. If an actor went on stage wearing a lion mask and making roaring sounds, the audience is ready to make believe that he is a lion.

A 1990’s stage play at Alliance Francaise, Nairobi: “Unlike movies, most theatre productions are minimalist in nature” (Photo: Alex Nderitu)

- Questionable awards

Now that the Mbalamwezi Awards are defunct, the only national award scheme for professional theatre in the country is the Sanaa Awards. However, these accolades, like most award programs, have not been free of controversy. Sahil Gada of Hoodwink 9 Theatre had this to say in an interview with popular news/entertainment blog, HapaKenya.com:

“We have enough passionate people but the greed for money is pushing people to do mediocre stories which do not do anyone justice, the actors, audience, and generally brings the industry down. Good example, last year we were nominated for the Sanaa awards, which are considered the Tony’s in Kenya, for Lion King. It was horribly organized, horribly done. The awards were useless. People were asked to vote for shows that they had not watched. That is the state of the industry. By the time the last winner was announced there were only five people. It was rubbish. Total waste of time. The system can be revived. If we are able to give incentives to motivate creatives. Just an appreciation for what we do, it would improve the whole thing. Once we do that the industry will attract investors who can put their marketing money in plays.”

Another nominee complained to me that an award ceremony he attended had too many people with names beginning with the letter “O”, suggesting that they all belonged to the same community. Kenya has about 44 distinct

“communities,” or “tribes,” and the monster that is tribalism often rears its ugly head.

- Lack of professionalism

Heartstrings Ensemble (originally Falaki Arts) is one of the most prolific and successful troupes in the Kenyan theatre scene. Past Heartstrings shows include Think Like A Kenyan At Like A Lady, My Fish My Choice, Girl In My Soup, Kihero To Iywagi, Behind My Back, and Who Let The Dogs Out? The group was co-founded by Sammy Mwangi and the now late Erastus Owuor back in 1990. Since then, many “giants” have been associated with it, including Victor Ber (a five-time Best Actor winner) and top comedian Daniel “Churchill” Ndambuki of TV’s Churchill Show fame. Heartstrings are some of the few theatre troupes that have been able to secure corporate sponsorships and to pack venues to capacity, sometimes staging extra shows due to public demand. But even this much-touted group has not escaped controversy. In recent years, some of their shows–virtually all comedic–seemed to have very loose scripts and large casts who appeared to be playing by ear. In one particular show, at the 300-pax Alliance Francaise (Fren Cultural Centre) auditorium, there were so many idle people on stage that one of them was checking his private mobile phone messages while the others worked. These issues did not go unnoticed by such personages as journalist/blogger Faith Oneya and veteran actor John Sibi-Okumu who at the time had a TV show on Kiss TV dubbed The JSO Interview. Below is a fragment of a discussion between John Sibi-Okumu and Daniel Ndambuki on The JSO Interview (Full interview available here)

John Sibi-Okumu: The criticism of Heartstrings as an ensemble, as a group, is that precisely because it has (actor) input. The kind of thing they can do (in one show) can never be replicated–it’s always sort of ad-lib, made-up-on-the-spot, lacks professionalism. Is this going to stay that same forever as you see it or what’s the next stage?

Daniel “Churchill” Ndambuki: The Heartstrings plays. It’s more of slapstick. It’s pop-corn theatre. “This (topic) is what is hot–let’s talk about it.”…We rehearse for the plays. Seriously. There’s no ad-libbing. Serious rehearsals…

Still, Heartstrings is one of the more popular groups with audiences and performers. There were groups that were so unprofessional or unserious that they were doomed to fail. For example, a troupe that was putting up one of my plays in Central Kenya had a “marketing manager” who couldn’t have gotten Mark Zuckerberg a job in the tech business. Instead of being “out there” promoting the upcoming show, the nincompoop was watching rehearsals and contributing ideas! He posted no fliers or posters, arguing that people in that town don’t read them. In the end, the cast (who were exhausted from daily rehearsals) had to go out and market the show themselves. Elsewhere, an angry young complained in a newspaper of how the producer of a show had transported his entire cast to a series of shows in Western Kenya. After the run–which grossed slightly over Kshs 200,000–”the guy picked up his girlfriend and went M.I.A. for several days. He wouldn’t even answer his phone.” Little wonder that, in an article entitled, Comedy Group Takes The Country By Storm, Zachary Ochieng wrote: “In a country where theatre companies have been closing shop in quick succession, comedy masters, Heartstrings Ensemble, have carved out a niche for themselves and are providing Kenyans with the laughter they so desperately need.” At least Heartstrings strive for excellence.

MARCHING INTO THE FUTURE

At the commissioning of the modernized Kenya National Theatre (September 4, 2015), the Head of State, President Uhuru Kenyatta said:

“Theatre is a great space where talent, innovation, vision, enterprise, freedom of thought and expression intersect. This intersection gives society an opportunity to examine itself, criticise itself, admire itself, understand itself, laugh at itself, teach itself, and move itself forward to a higher, better socio-political and moral plane.”

Incidentally, Uhuru’s wife, First Lady Margaret Kenyatta, attended a showing of Ntozake Shange’s For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide/When The Rainbow Is Enuff at the now defunct Phoenix Theatre. The famous all-female “choreo-poem” had been staged by veteran thespian Mumbi Kaigwa (The Art Canvas).

In a past online article titled My Thoughts On Criticism Anne Manyara wrote:

“It is said that King Louis XIV (1638 – 1715) of France, a great lover and patron of the arts, and because of whom classical French literature and music flourished, asked the critic Nicolas Boileau (1636 – 1711) to comment on a poem he had written. Boileau, obviously torn between upsetting the king and telling the truth–as a good critic does–replied, ‘Nothing is beyond Your Majesty’s power. Your Majesty set out to write a bad poem and has succeeded brilliantly!'”

Like a lawyer in a courtroom, I would like to argue that it is the theatre groups–not the critics–that have broken faith with Kenyan audiences, leading to half-empty venues. My closing argument, Your Honour, is that Kenyan theatre holds great potential if only more professionalism and better marketing techniques can be injected to the mix. As for the theatre companies, let’s just say that some of them have set out to stage mediocre productions and they have succeeded brilliantly!

Below are a few online videos on the current state of Kenyan theatre:

Kenyan thespians on Acting And Theatre (Citizen TV):

State Of Theatre In Kenya (Film Speak):

Iconic Theatre In Kenya’s Mombasa Struggles To Stay Open (Al Jazeera TV):

Daniel “Churchill” Ndambuki on The JSO Interview (Kiss TV):

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Alexander Nderitu.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.