“If you say in the first chapter that there is a rifle hanging on the wall, in the second or third chapter it absolutely must go off. If it’s not going to be fired, it shouldn’t be hanging there.’” – Anton Chekhov

‘Writing’ can often be misconceived as a rather straightforward artistic medium. After all, you put the pen to paper and let your thoughts do the talking. Isn’t that how it goes?

Perhaps in some cases it does, but not all written works can be the diary entries of a genius mind – some have to be organized by said wordsmiths into architectural worlds of intricate themes and intriguing characters; and hammering all those pieces into place requires a certain amount of skill.

Many great writers are not only natural-born storytellers, but innovators of the craft. Each has a method to the creative madness of scripture, and it is these methods that are studied by forthcoming generations in efforts to replicate even a modicum of the finesse with which great works are laid upon the page.

Anton Chekhov is a name that is revered throughout literary circles the world around. As one of the most prolific short-story writers in modern literature, even such creative writing heavyweights as James Joyce and Virginia Woolf have admitted admiration for the great Russian storyteller. Yet it is not just the ability to captivate a reader’s attention that makes Chekov stand out amongst the literary elite, it is his aptitude to do it with efficiency and methodical poise.

Writing short stories is an art form in itself – and a most difficult one at that; as William Faulkner once said:

“I’m a failed poet. Maybe every novelist wants to write poetry first, finds he can’t, and then tries the short story, which is the most demanding form after poetry. And, failing at that, only then does he take up novel writing.”

The smaller the canvas, the bigger the role of each stroke; therefore it takes a particular amount of proficiency and planning in order to make a short story work and achieve its desired impact on the reader. Chekov understood that in order to deliver the payload within the confines of a limited word count, every detail has to play its part, and not a single morsel of space should be wasted.

And so, in walks the man with a gun.

‘Chekhov’s Gun’ has become a well-known and respected literary principle ever since the writer spoke of the concept in his letters. The idea is quite simple: “if a gun is present within the first act, it should go off by the end of the third.” The presence of a prop that has no use within the context of a play or a story baffled the writer, as he viewed it as wasted of creative space, and thus suggested that anything that is not used to drive the story should be removed from it – for writers should not make falls promises to the readers. Other interpretations of the proverbial firearm have also included the notion that a seemingly inconsequential object can play a pivotal part within a given story, and bring an air of foreshadowing to a particular narrative.

Perhaps the most popular example of this “locked and loaded” theory is seen in Chekhov’s play The Seagull. In one instance of the play’s second act, the young playwright Treplyev enters the house with a rifle and a seagull that he had just shot with it, shortly before mentioning that one day he shall be just like the seagull. Treplyev would then go on to shoot himself with the same rifle at the end of the fourth act, thus bring the notion of foreshadowing to fruition.

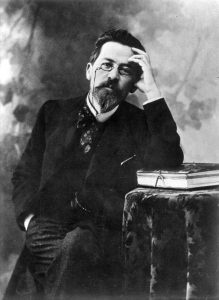

Anton Chekhov, 1902

The said principle has since then branched out far beyond pages of books and the halls of the theatre. A popular driving force in Hollywood scripts and episodic TV writing, this seemingly straightforward motive of object implication can serve as somewhat of an anchor to an otherwise conventional voyage, causing a wave that alters the course towards unexpected destinations.

Of course, this is not to say that every such nominal object will always play a significant role further in the course of the story – there have been plenty of instances within creative writing of the trigger never being pulled on the weapon in question. That, however, does not detract from the utility of an outlined object, for in the case of inactivity, it simply assumes the form of a ‘red herring’ and distracts the audience from a twisting plot progression; thus continuing to serve a purpose within the context of the narrative. And whilst this may not coincide with Chekov’s belief of “not making false promises to the reader”, it is nonetheless a popular literary device in its own right; and every writer has their own idea of how the story goes.

Great writing will always find ways to intrigue and excite audiences, but great writers will also create blueprints for this to happen. Not only was Anton Chekhov a talented author, but a student of his craft, and a teacher to future generations…proving that even modest prose can have the impact of a smoking gun.

This article appeared on RussianArtAndCulture.com on May 27, 2020, and is reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Anton Sanatov.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.