Although historically Polish theatre has gained worldwide renown predominantly thanks to its male directors, Poland today has a thriving and influential cadre of young women directors, who have gained renown and respect in Poland and abroad. Following the 1989 Round Table talks that ended the forty years of communist regime in Poland, the Polish theatre—always entangled in one way or another in the political struggle—suddenly was left in an ideological and financial vacuum. At the same time, with the emergence of free society, the public debate moved from theatres to the parliament and the media.

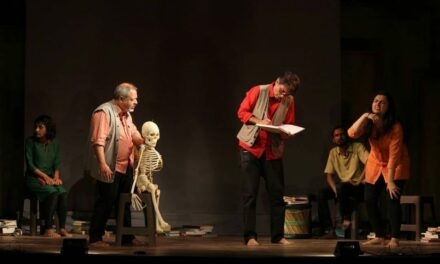

Maja Kleczewska’s production of Macbeth

at the Jan Kochanowki Theatre in Opole, 2004.

Culturally, on the crossroad between the traditionally Catholic-centered mentality of the old Poland and the newly emerging class of women unwilling to accept its patriarchal underpinnings, during the 1990s, Poland became a battlefield between religious and liberal groups. Many women became bitterly disappointed with the direction of the country, becoming nostalgic for socialism, often referred to as a period of “gender innocence.” Despite the obstacles, or perhaps because of them, the transitional period of the 1990s included small political victories. In 1989 Izabella Cywinska, theatre director and critic, became the first Minister of Culture. Only a decade earlier Cywinska had been imprisoned for one of her politically engaged productions.

Unfortunately, during the 1990s, no theatre was willing to discuss the social issues of the day (including the emergence of the Catholic right and its influence on the Polish law). The function of political and social commentary was predominantly relegated to performance and visual art, which pursued the paradoxes and ironies of the Catholic discourse vis-à-vis gender difference and sexuality. Women performance and visual artists such as Katarzyna Kozyra, Alicja Zebrowska, and Dorota Nieznalska caused scandals by either mocking or shocking the Polish public opinion with radical juxtapositions between the sacred and the profane.

“Today, Polish women directors appear to thrive in the post-communist world.”

The years 2001 through 2003 saw directorial debuts of many young women directors, some of whom eventually came to establish themselves as leaders of Polish theatre. They include Maja Kleczewska, Iwona Kempa, Agata Duda-Gracz, Aldona Figura, Grazyna Kania, Agniesza Glińska, Monika Strzępka, and Olga Lipinska. Today, Polish women directors appear to thrive in the post-communist world. In 2011, for example, the Grand Theatre in Poznań announced that its season would be devoted solely to women directors and the Stara Prochoffnia Theatre in Warsaw has started organizing “women only weekends” for their women audiences. Working in this climate, the new generation of women directors is not afraid to take risks and tackle difficult subjects on both small and grand scales.

Maja Kleczewska’s production of Macbeth

at the Jan Kochanowki Theatre in Opole, 2004.

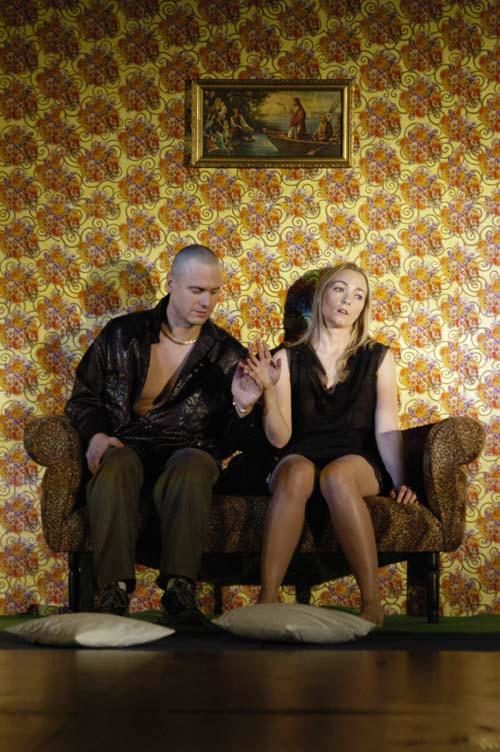

Born in 1967 Iwona Kempa graduated with a degree in Theatre Studies from Jagiellonian University in 1992 and studied directing at the State School of Theatre in Cracow, graduating in 1996. She debuted as a director in 1994 at the Universal Theatre (Teatr Powszechny) in Łodź with a production of Quartet by Bogusław Schaeffer. Combining quasi-theatrical and quasi-instrumental elements, Quartet was so successful that during the 1990s it was staged by practically every Polish theatre. In 1996 Kempa began working in Toruń at the Wilam Horzyca Theatre (Theatre im. Wilama Horzycy), where she directed Caricatures (Karykatury) by Jan August Kisielewski. For this production she received the Bohdan Korzeniewski Prize, awarded to young directors by the magazine Teatr. Her other productions in Toruń included Beckett’s Endgame in 1998; Two and Half Billion Seconds—based on Beckett’s five one-acts—in 2006; and Martin McDonagh’s The Lonesome West in 2002. All three productions received critical acclaim, with The Lonesome West winning the Minister of Culture and Journalist Awards.

Kempa is mostly interested in contemporary drama, and she directed a number of Polish premiers of international hits, including McDonagh’s The Cripple of Inishmaan in 1999 at the Wrocław Contemporary Theatre (Wrocławski Teatr Współczesny), Zoltan Egressy’s Portugal in 2004 at the Polish Theatre in Poznań, and Neil LaBute’s The Shape of Things in 2003 at the Polish Theatre in Bydgoszcz. Her production of Portugal was met with critical acclaim, and Zoltan Egressy, the author of the play, praised Kempa for a perfect balance between pathos and grotesque. The production also won a number of awards, including the 2004 directing award at the IV Festival of Contemporary Drama “Reality Represented” in Zabrze. Kempa’s productions of classics include Chekhov’s Seagull in 1999 at the Jana Kochanowskiego Theatre in Opole, Carlo Gozzi’s The Love of Three Oranges in 2002 at the Contemporary Theatre in Wrocław, Büchner’s Woyzeck in 2003 at the Wilam Horzycy Theatre in Toruń, Brian Friel’s Dancing at Lughnasa in 2006 at the Theatre Academy (Akademia Teatralna) in Warsaw, and an adaptation of Ingmar Bergman’s Scenes from a Marriage in 2008 at the Juliusz Słowacki Theatre. Kempa chooses productions that combine humor with irony, violence, pathos, and the grotesque, focusing on carefully crafted emotional range and subtle study of characters.

“The central theme of Kleszewka’s work is crime, murder, and violence.”

Maja Kleczewska was born in 1973 in Warsaw. She graduated with a degree in psychology from Warsaw University and a degree in directing from the State School of Theatre in Cracow. She was an assistant of Krystian Lupa and Krzysztof Warlikowski, internationally knownPolish theatre directors. Her 2000 directorial debut, Jordan by Anna Reynolds and Moiry Buffini, staged at the Juliusz Słowacki Theatre, won her immediate critical praise. Kleczewska’s productions analyze the psychology of the characters and their motivations, showing lonely and lost heroes who are unable to adapt to their world and eventually end up either going insane or committing a crime. The central theme of Kleszewka’s work is crime, murder, and violence. Her direction is rough and unsentimental. Kleczewska’s most acclaimed production was Shakespeare’s Macbeth, staged in 2004 at the Jan Kochanowki Theatre in Opole. The production combined Shakespearean language with modern aesthetics of pulp fiction movies. Journalist Peter Rieth poignantly summarizes the impact of the production, explaining,

Kleczewska’s Macbeth takes the ostentatious step of making Shakespeare’s witches—weirder. Rather than witches, the drama unfolds with what appear to be two transvestites and a prostitute. Such an opening salvo may initially be regarded as an application of stereotypically modern crassness to an ancient classic, but Kleczewska’s apparent genius lies in the fact that she recognizes modernity as effectively crass, thus transmutating Shakespeare’s “weirdness” from an acknowledgment of the mystic frontiers of Fortuna into a representation of modern decadence. This very transmutation is essentially the foundation for the play’s dialectic regarding the possibility of tragedy and the question of farce.

In Poland, the production provoked scandal, because, as Jacek Wakar, a Polish theatre critic pointed out, it “features sex and violence similar to a Tarantino movie.

Agata Duda-Gracz is a theatre director and designer. Her father, Jerzy Duda-Gracz is considered one of the greatest contemporary Polish painters. Born in 1974 in Cracow, Duda-Gracz graduated with a degree in art history from the Jagiellonian University in Cracow and studied directing at the State School of Theatre in Cracow. She worked on more than twenty productions either as a director, scenic designer, or costume designer at theatres in Kalisz, Cracow, Lódź, Warsaw, and Wrocław. She began her career with the production of Cain by George Byron, staged at the Witkiewicz Theatre in Zakopane in 1998. Other notable productions include her direction at the Theatre Academy of Dramatic Arts in Cracow of Karl Büchner’s Woyzeck in 1999 and Jean Genet’s Balcony in 2004; her direction at the Juliusz Słowacki Theatre of Vailland’s Abelard and Heloise in 2002 and Camus’s Caligula in 2003; Shakespeare’s Othello in 2009 at the Jaracz Theatre in Łodź; Father, based on a short story by Oscar Tauschinski, in 2010 at the Juliusz Słowacki Theatre; and Giacommo Puccinni’s La Boheme in 2011 at the Grand Theatre (Teatr Wielki) in Poznań.

Duda-Gracz’s Everyone Needs to Die Someday, or Trojan War, based on Shakespeare’s Troilus and Cressida.

Duda-Gracz designs costumes and scenography for her own shows as well as for other shows, and she has won a number of awards for her designs, including a Ludwig Award for the set of Abelard and Heloise. In 2009 she was awarded a Golden Laurel for her Mastery of Arts, an award given by the Polish Culture Foundation in Cracow. She is often called a “visionary” due to her larger than life, symbolic, and rich visual imagery. Her productions are often compared to those of Józef Szajna and Kantor, two of Poland’s most renowned theatre directors who began their careers in visual arts. Duda-Gracz’s breakthrough production was Galganberg, a collage of texts by Michel de Ghelderode, staged in 2007 at the Słowacki Theatre in Cracow. The production has been hailed as her best show yet, earning critical accolades. Most recently, Duda-Gracz has been staging productions not only of her own design but also for which she writes her own texts, as with Apocalypsis: A Short History of Marching, staged at the Słowacki Theatre in Cracow in 2011. Critically acclaimed for its visual and ritualistic aspects (the viewers were sitting in church-like pews), the production marked a new direction in Duda-Gracz’s career; however, like her previous productions, it was called “strong” and was filled with haunting images of violence and sexuality.

From International Women Stage Directors, edited by Anne Fliotsos and Wendy Vierow. Copyright 2013 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois. Used with permission of the University of Illinois Press.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Magda Romanska.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.