It is an interesting coincidence that 1973 saw the creation of both Pina Bausch’s Tanztheater Wuppertal and the Polish Dance Theatre–Poznań Ballet.

It would seem that Poland’s rich pre-war tradition of expressionist dance, one that made it an important center for the movement (alongside Germany and Austria), would provide the perfect soil for the genre known as Tanztheater. The full tradition of expressive dance was never revived after the war, but a handful of cities, including Poznań and Gdańsk, still bore the signs of the once-rich movement. The curriculum of the Poznań Ballet School featured elements of expressive dance. The form also inspired the choreographic language of Janina Jarzynówna-Sobczak, a student of Ruth Sorel, who in turn was the assistant of Haral Kreutzberg.

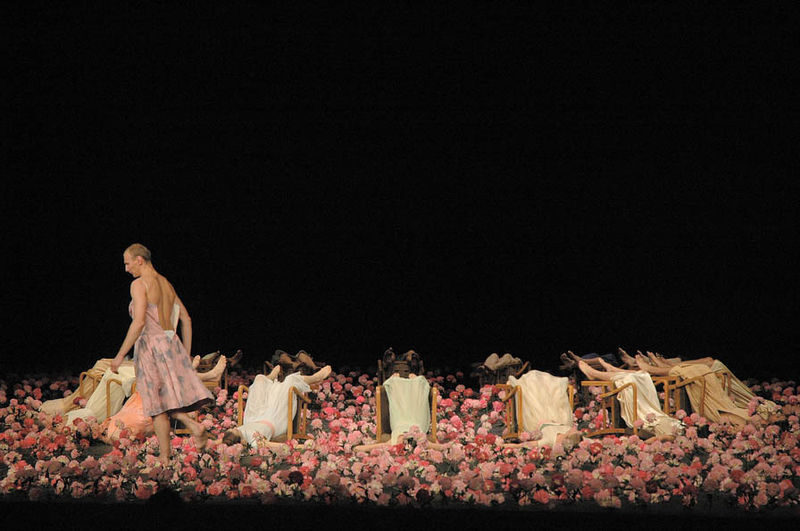

Béla Bartók, The Miraculous Mandarin. Choreography by Konrad Drzewiecki Poznań Opera, September 1973.

Expressionist Dance

Also known as Ausdruckstanz, German Tanz, and expressive dance. The form was developed in Germany in 1910–1930, in opposition to classical ballet. Expressionist dance leaned heavily toward original methods used by individual choreographers, relying on improvisation and the expression of the dancer’s emotions. In terms of aesthetics, the genre borrows from the Expressionist movement. Key names in expressionist dance include: Rudolf von Laban and his students Mary Wigman and Kurt Joss, as well as Gret Palucca, Harald Kreutzberg, Yvonne Georgi, Hanya Holm, and others.

In post-war Poland, ballet was undeniably the preferred technique. Inspired in the 70s by the work of the Soviet school of dance, ballet received more promotion than in previous years. At the same time, the number of dancers associated with the expressionist school began to dwindle. The retirement of Janina Jarzynówna-Sobczak in 1975 was the most significant marker of this shift.

And yet in spite of this tendency, Conrad Drzewiecki was given a theatre in 1973 in which to stage performances based on modern dance techniques (mainly using the technique of Martha Graham). The creation of a state-run theatre in a country where ballet was the dominating aesthetic can be regarded as a purely political gesture, a precedent of sorts, albeit one that had an enormous impact on the art of dance. After nearly ten years of waiting, Drzewiecki was given a stage and permission to conduct his choreographic experiments. What is most surprising, however, is that he never described the character of his theatre as “experimental.”

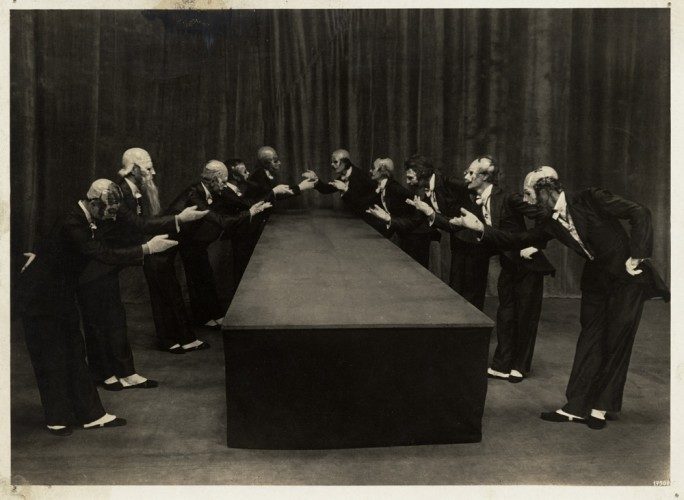

The Green Table, choreography by Kurt Jooss, 1932

It is an interesting coincidence that 1973 saw the creation of both Pina Bausch’s Tanztheater Wuppertal and the Polish Dance Theatre–Poznań Ballet. Both theatres sparked a new tradition and a new way of thinking about dance, and yet despite the presence of the words “dance theatre” in both names, the two institutions differed in formal and aesthetic terms.

Tanztheater

Tanztheater (literally: dance theatre) refers to both a type and a genre of dance. In the narrow (genre-specific) sense, it is a term created by critics and theoreticians to describe the specific character of German dance in the 70s and in later years. Its roots may be found in the Ausdruckstanz (also known as expressive or expressionist dance) of the early 20th century. The genre developed into an entirely novel form in the 70s, and is commonly associated with choreographers born during World War II, such as Johann Kresnik, Pina Bausch, Susanne Linke, Reinhild Hoffmann, and Gerhard Bohner. Features of the genre include the use of such strategies as collage and montage. In contrast to Ausdruckstanz, Tanztheater never developed any movement or dance techniques of its own. In describing this form, Patris Pavis emphasizes that the goal of Tanztheater lies not in dance, movement, or choreography itself, but in the creation of a fully theatrical spectacle through the use of dance.

Let us briefly examine the ties between the Polish dance scene and the German Tanztheater tradition. It should be noted that the first Polish performance of Kurt Jooss’s The Green Table took place in 1972, a full four decades after the German premiere. The Polish cast of the performance staged in Łódź, featured Ewa Wycichowska, who became the director and lead choreographer of the Polish Dance Theatre a few years later. She recalls her work on The Green Table:

“The next step was to meet Kurt Jooss and take part in the production of The Green Table in 1972. It was then that I understood that dance theatre was what interested me. (…) It was the first time a still-topical, politically-charged production had been staged in Poland. It was theatre, not a ballet show. The music and set were kept to a minimum. We had two pianos, sets that we would change by ourselves, and the whole performance took 45 minutes. The dance techniques were geared toward expression, quality of movement, and truth in movement. (…) I think it was the start of what I wanted to do in my own work as a choreographer, what I looked for in France, and what I later implemented at the Polish Dance Theatre with a new generation of dancers and for a new generation of audiences.”

It would be hard to find a more telling account of an artist inspired by Kurt Jooss. As a choreographer, Wycichowska has always placed special emphasis on quality of movement, although pinpointing just what she meant by “truth in movement” in the above quote isn’t as easy.

Wycichowska’s choreography is based on modern and classical techniques. In terms of set design, Wycichowska doesn’t shy away from monumental, impressive decorations, as in Carpe Diem and Walka K@rnawału Z Postem (The Fight Between Carnival And Lent), departing from Jooss’s tenets. One thing is certain: her work on The Green Table had an enormous impact on her choreographic style.

Pina Bausch in Café Müller, 1978 photo courtesy of Jochen Viehoff.

While Polish audiences had to wait quite a while for the production of The Green Table, they were introduced to the repertoire of Jooss’s student, Pina Bausch, much quicker. Tanztheater Wuppertal performed in Wrocław in 1987. In the European history of dance, over four decades separate The Green Table and the Pina Bausch pieces presented in Wrocław: Frühlingsoper (The Rite Of Spring, 1975) and Café Müller (1978). From the perspective of Polish audiences, the interval was a relatively short fourteen years. It is also worth mentioning that Bausch had two Polish dancers in her cast at the time: Janusz Subicz was a permanent member, while Piotr Galiński was doing an internship. In 1998, Pina Bausch paid another visit to Poland, as part of Warsaw’s CROSSROADS International Meeting of Live Arts. Tanztheater Wuppertal was celebrating its 35th anniversary. The theatre’s second Polish performance introduced local audiences to a much more innovative Bausch piece, Nelken (Carnations), the style of which is representative of proper, mature Tanztheater.

Would Bausch’s work enjoy such popularity in Poland had audiences been exposed to Nelken—which employs collage and a theatrically “cut up” narrative with no plot—before seeing Café Müller, which can be told as a story but lacks a consistent narrative? I feel that would not have been the case. What Polish choreographers (Ewa Wycichowska, Jacek Łumiński, Witold Jurewicz, Iwona Olszowska, Hanna Strzemiecka) expect of performances and performers is above all a demonstration of technique and skill—a result of their fascination with dance steps other than those used in ballet. Placing these displays of dance into a theatrical setting gives them an air of experiment and novelty—and that’s enough for most choreographers, who see dance as an end in itself. It is for this reason that many of them see no need to cross the boundaries of the art. They appreciate displays of dance and composition of movement—so one may conclude based on their work in the 1990s.

The pieces Bausch presented during her troupe’s first visit to Poland were rich in both technical and theatrical dance. Polish choreographers were able to appreciate this combination of dance and theatre. Yet they are skeptical about forms that break too sharply with dance techniques, or forms in which the boundaries of dance are so broad as to include any form of human movement. That is how far Pina Bausch had gone in her search for a new choreographic language, and that is what made her the genius she was, while also condemning her to the criticism of traditionalists. Her attitude of defending dance for the sake of dance and her emphasis on the need to demonstrate dance techniques in dance theatre seemed to define the generation that took to Polish stages in the 90s. It should be noted that the Tanztheater Wuppertal’s appearances in Poland opened and closed the decade of the 90s, a period which encompassed the events and the growing popularity of what we in Poland have, somewhat mistakenly, named “dance theatre.”

Excerpt from the book Sztuka Do Odkrycia. Szkice O Polskim Tańcu (Art Ripe For Discovery. Essays On Polish Dance), by Anna Królica, published to coincide with the OPEN STAGE International Theatre Dance Festival in Tarnów, held by the Mościce Cultural Centre (October 1-16, 2011). biweekly.pl is a media patron of the festival.

Translated by Arthur Barys.

This post originally appeared on Biweekly.pl and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Anna Królica.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.