How To Rule The World is Indigenous playwright Nakkiah Lui’s critical riposte to the intellectual poverty of political life in Australia. A biting and urgent satire of the politics of fear around race, it had the audience guffawing and cringing with recognition in equal measure.

Set in the corridors of Canberra, Lui’s story is particularly disturbing because it illustrates how ripe our political class are for satirical representation. The most unnerving element of this political farce is that the gap between the story it tells and the headlines of recent years is not very large. Even the set design ingeniously evokes the pale modernism of Parliament House with unsettling effect.

As one of the characters later remarks in the play, this story begins when “an Aboriginal, an Asian, and an Islander” walk into a bar in Canberra. But this is not the premise for a racist joke (though the play is a set of jokes about race). The booze and cocaine filled meeting between three bright young political things produces a plan to work a system that has systematically excluded their voices.

Vic (Nakkiah Lui), Zaza (Michelle Lim Davidson), and Chris (Anthony Taufa) are political insiders who are frustrated by their repeated exclusion from power. They are equally disturbed by a policy proposal from the Prime Minister (a scene-stealing Rhys Muldoon) that promises to shore up Australian borders while essentially imposing cultural uniformity.

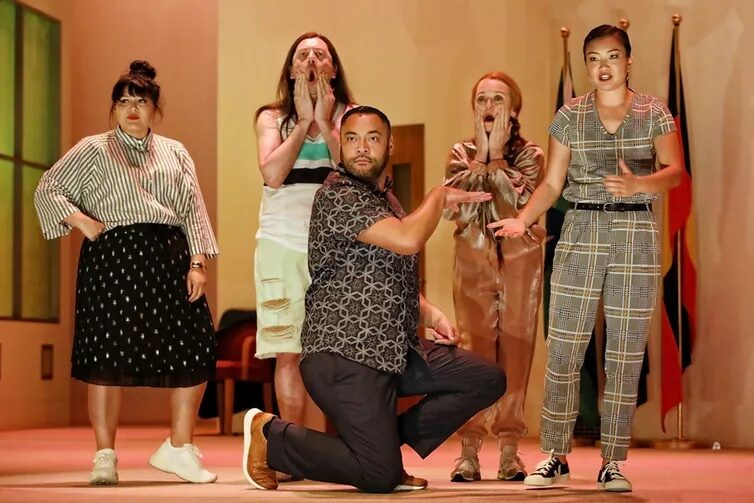

Nakkiah Lui, Hamish Michael, Anthony Taufa, Vanessa Downing, and Michelle Lim Davidson in How To Rule The World. Photo Credit: Prudence Upton

They hatch a plan to get a dopey white man, Tommy (Hamish Michael), elected to the Senate to block the PM’s policy, and the hilarity begins–with an important detour via the preference whisperer to game the system and ensure their candidate’s success.

Vic, Zaza, and Chris find themselves confronted with a series of dilemmas about how far they are willing to go to pursue their goal. And by the time the interval rolls around, the characters and audience alike are shocked by how quickly these outsiders have started playing the tricks of political insiders.

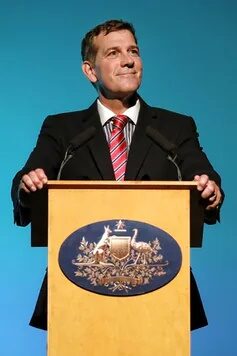

Rhys Muldoon is scene-stealing as the Australian Prime Minister. Photo Credit: Prudence Upton

What causes and people are they willing to sacrifice in order to achieve their ends? Indeed, the unity of these characters soon starts to fray under the pressure of political life.

Their different experiences begin to fracture complacent assumptions of “woke” solidarity. After all, what does a queer Tongan man actually have in common with a wealthy Korean woman?

How To Rule The World asks challenging questions about the cost of tarrying with the levers of political power. No one comes out of this play uncompromised, and the most biting critiques are saved for characters who seek to change the world in the name of left-wing political virtue.

Lui clearly wonders how, or perhaps if, underrepresented voices can play our political game without falling prey to its horrifying forms of political calculus.

This play has clearly emerged from a generation steeped in the politics of intersectionality, but with a suspicion about its effects. If political ideas can be mapped onto generations, this is a work shaped by and written about ideas that represent the bread and butter for an emerging political cohort.

At its best, intersectional thinking offers a way to think through how different identity categories intersect to produce incomparable experiences of oppression and privilege. It keeps us alive to the dangers of assuming that the solution to the wicked problem of inequality is some kind of naïve humanism or, even worse, an assertion of “pull yourself up by your bootstraps” individualism.

When Vic, Zaza, and Chris hilariously tear apart the ideas of a young white man claiming reverse racism in the early scenes of the play, we see the power of this political thinking in front of our eyes.

At its worst, however, intersectional thinking slides into an account of oppression and marginalization that suggests they can be measured on some kind of gauge. It becomes an imaginary scorecard on which the amount of oppression points awarded determines the political and cultural restitution required.

Nakkiah Lui is an important voice in Australian theatre. Photo Credit: Prudence Upton

Lui is acutely aware of how easily this can be weaponized as a form of political calculus concerning who should bear the cost of a desired political outcome. This way of thinking means Vic, Zaza, and Chris soon start meting out rather horrifying consequences to those who are “less” oppressed. Lui clearly has searching questions to ask about the moralizing certainties that intersectional thinking can encourage.

Lui is an important voice in the Australian cultural landscape, and this is her fourth new piece at the Sydney Theatre Company in three years. These are exactly the voices that a company like this should be both nourishing and showcasing–for she is telling uncomfortable stories that refuse easy political containment.

While there were a few clunks and kinks in the storytelling after interval, this is, perhaps, the product of a set of questions that require some blunt responses. The monologues that argued for treaty might not have been the smoothest moment of storytelling I’ve seen on stage, but they had the audience on the edge of their seats.

How To Rule The World is playing at the Sydney Opera House until March 30.![]()

This article appeared in The Conversation on February 26, 2019, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Leigh Boucher.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.