James Saunders is one of British theatre’s forgotten playwrights. Although he wrote some 70 plays during a career spanning about four decades, he remains largely unknown, despite the occasional revival, such as that in 2011 of his 1963 surreal hermit story, Next Time I’ll Sing To You. This neglect may be because his rather absurdist and idiosyncratic view of the world has fallen out of fashion, or it might be that he’s a casualty of the increasing timidity of many of our current theatres, which prefer an American prize-winner to a risky Brit. So it’s great to be able to say that this revival, by the enterprising Two’s Company, of his 1977 drama, which had a West End run in 1979, is both emotionally thrilling and intellectually satisfying.

At first sight, Bodies appears to be a standard account of middle-class adultery. Two suburban London couples — Mervyn and Anne, David and Helen — cheat on their spouses, swap partners and break up their homes. Then the couples get back together again. To live in quiet and not so quiet resentment. But there’s nothing standard about how Saunders tells the story, which begins with individual narration direct to the audience, and gradually develops into dialogues past and present. Nor is there anything standard about the content. For this is also an abrasive account of a therapy fad and of a teacher-pupil relationship, as well as being a passionate-filled declaration of what it is to be fully human.

Middle-aged Mervyn and David have been friends for many years, despite their different outlooks on life. Mervyn is a head teacher, who really enjoys teaching English literature to his sixth form, while his friend is a corporate executive, working in marketing and enjoying life as a Sunday painter. When Mervyn’s wife Anne casually drifts into an affair with her husband’s best friend, David’s wife Helen finds out and decides to seduce Mervyn as an act of revenge. Although these affairs temporarily break up the two marriages, both couples get back together again. Then David and Helen go to the United States, while Mervyn and Anne remain in Ealing, West London. When, after nine years, David and Helen return to London, Mervyn decides to invite them over for dinner.

It slowly emerges that the headmaster sees a link between the experiences of his former friend and former lover, and those of a pupil called Simpson, a suicidal boy who he has been unable to save from despair. While in the States David and Helen have been successfully “cured” of their neuroses by a form of group therapy, which is unspecified in the play but identified in the programme as Erhard Seminars Training (EST), a cult-like phenomenon that started in San Francisco in 1971. As a result, they both feel liberated from their oppressive childhood memories and psychological habits, including presumably their desires to have sex with other people. They also have acquired the EST worldview: as David explains, this involves feeling centered in the moment, in your body, taking responsibility for your actions but without giving meaning to them, freeing yourself of tormenting thoughts.

Like Peter Shaffer’s Equus in 1973, the intellectual conflict of Saunders’s play, which explodes during the exciting second half as the two couples meet again for the first time in ages, centers on the idea that therapy can both cure you and rob you of your subjectivity. Therapy cures neuroses, but leaves the patient less than human, substituting logic for absurdity and ironing out idiosyncrasies. Unlike Equus, Bodies doesn’t attempt to explain away the dysfunctional mental states of its characters, and the conflict is as much about resentment, guilt, and regret, as it is about EST or any other faddish therapy. Instead, what we get is a brilliantly impassioned series of speeches, which occasionally resemble those of Jimmy Porter in John Osborne’s Look Back in Anger, in which Mervyn articulates his view of our shared humanity.

Saunders constructs his play with great craftsmanship, and at its best his writing is both passionate and provocative, challenging the audience to consider what might be lost through therapy, as well as what might be gained. Although the characters of Anne and Helen are a bit under-written compared to the men, the playwright does give them the barbs of perception and the occasional feminist point, all of which accurately strike home. The subplot involving the teenage Simpson — who resembles Alan Strang in Equus — remains offstage, but comes alive right in front of us whenever Mervyn talks about it. As a cry from the heart, Bodies is thrillingly alive, both stimulating and moving.

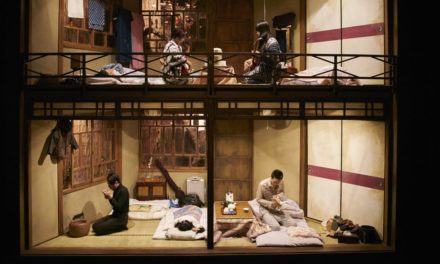

And this is also due to Tricia Thorns’s scrupulous production, which takes place on Alex Marker’s open set, furnished in 1970s style, complete with Newton’s cradle and cream plastic phone. Her well-balanced cast are consistently good, with Annabel Mullion and Alix Dunmore providing depth and incisive presence to Anne and Helen, while Peter Prentice’s David becomes increasingly controlling as the evening passes. As Mullion strikes a note of exasperated sadness, Saunders’s view of human relationships finds a striking contrast: Tim Welton grows increasingly uninhibited and fiery as Mervyn drinks more and more whiskey, with his final speeches reaching the heights of feeling, proclaiming a disheveled manifesto for life beyond a perfectly well-balanced psyche (as eventually portrayed by David and Helen). It is great to see this modern classic revived with such energy and conviction.

Bodies is at the Southwark Playhouse until March 9.

This article first appeared in Alexz Sierz on February 15, 2019, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Aleks Sierz.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.