In the celebratory cookbook Cake, Maira Kalman writes:

“When we lived in Rome we had a party and we made a gorgeous pink cake. Lucretius was on our mind. And Spinoza. His search for happiness. And someone mentioned Nietzsche’s quote. He said a day without dancing is a wasted day. You don’t think of philosophers dancing, especially Nietzsche. But apparently they do.”

I had this idea in mind as I watched OnlyHuman by Christine Bonansea Company at Danspace Project at St. Mark’s Church. Kalman’s aphorism brings out not only the centrality of dancing in a life well-lived but also the improbability of a dancing Nietzsche. Like Kalman, Bonansea invites us to ask: what does it mean to dance? And what does it mean to be human?

The piece has three sequences–a fuzzy, looped video projection, a solo movement sequence, and group choreography. Each part highlights a different theme of the work: technology, biology, society, all of which are reshuffled and recombined in the successive sequences. From the top, we are confronted with the strangeness of the show, as the solo performer Mei Yamanaka moves through the darkness, lit only by the Blair Witch-style footage on the screen behind her. After the film projection ends, Yamanaka stands perfectly still, in perfect silence, for a few agonizing minutes. Every sound in the building is audible, and I felt like a rube wondering repeatedly, are those footsteps and that door shutting part of the show? Then I realized–my focus was being sharpened, the stillness and silence forcing me to concentrate on minute movements and sounds which only gradually got large enough for my brain to recognize them as these things called dance and music.

The group alternates between cooperation and (self-)destruction. Photo by Gaia Squarci

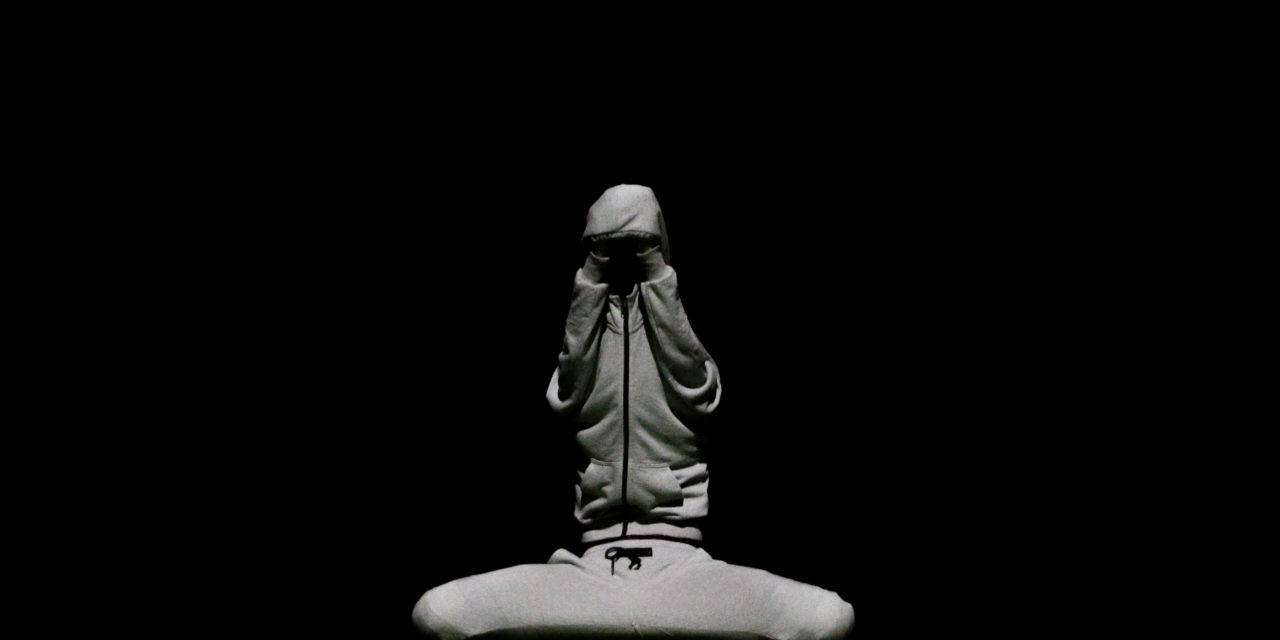

Yamanaka’s excruciatingly controlled movements during the solo were not dancerly per se, nor was the soundscape at all harmonious. Dressed in grey sweats that concealed her age and gender, she resembled one of the Doric columns that divide the chapel’s space. Her movements were elemental. Sometimes she pivoted her torso holding her arms at right angles, evoking industrial machinery. At other times she crouched low and hopped, looking positively simian. Is this what it means to be human? A primate with a brain-machine?

For me the most touching moment was when Yamanaka reached her hands up into the hood of her sweatshirt, stretching it up above her head to reveal her mid-section clad in a black leotard.

Moving her hands around the hood in an expressively curious way, she had transformed her own body into a human-like puppet. It was funny and ingenious, and reminded me of a notion that I came across in Scott McCloud’s book Understanding Comics–people will always read a circle with two dots and/or a line as a human face. Yamanaka’s face betrayed no emotion throughout her dance, but her person-puppet was coy and playful, more human than human.

When Yamanaka is joined by the rest of the company, the same movements reappear and take on a new meaning. What was so defamiliarizing when performed alone seems so much more recognizable as dance when done by a group performing in unison. This is one of the darker truths about human society, the permissiveness that multiplicity accords to actions. The sensuality of the choreography is evident only in the context of the group and the diads that break apart from it, the dancers in the company by turns cooperative and vulnerable. It’s dark and unsettling, and the wide range of possible meanings could point to a bleak Nietzschean nihilism. The theatre’s capacity is small, and the enthusiastic applause of the two dozen or so audience members seemed an inadequate thanks for the sheer physical labor performed for our entertainment. But after the ovation, the dancers came out of their professional mode, mingling with friends in the cast and audience, hugging, laughing. They’re human after all.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Abigail Weil.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.