“Laaaadies and gentlemen,” a TV host’s animated voice says out of speakers in the semi-dark, “it’s time for migrants to show that theeeeey’ve got talent!”

In an instant, the host–a middle-aged man with white beard and a tuxedo in the blue and yellow stripes of the Ukrainian flag–makes his way to the stage from the audiences’ seats. Next to him, there are five big white checkered market bags, a road sign, a guitar and a table covered in a British flag on the stage.

Just before the performance, each spectator has been given a green and a red card instead of a ticket. We are part of the show. We are “the Great British Public.” We decide, the TV host tells us, “who stays and who goes to the wrong end of Europe.”

The idea is: now that Brexit is supposed to take place, migrants are in a position to convince Britons they deserve to stay in the UK. If you want them in, lift your green card. If lucky, they celebrate the moment by having a selfie with the two judges, the TV host, and… a cardboard Queen Elizabeth II. If you want them out, lift your red card, and send them back to where they came from.

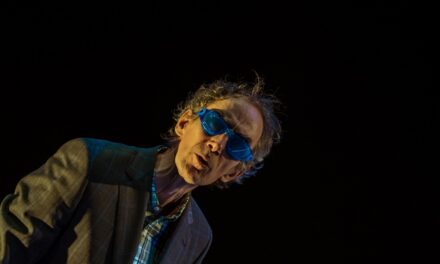

But the audience only votes at the end. During the show, two judges vote. They are the Brexiteer and the liberal. Nigel and Nigella. Nigel is British born and says no to almost every participant. In contrast, Nigella takes everyone in. She once was an illegal immigrant herself. She started off as a cleaner at the BBC, got noticed and was duly cast as “gypsy beggar number two.” She’s made it, and this is apparent in her physique: a charming smile and a perfect body, dressed in a glamorous sparkling evening dress and bright pink high heeled shoes.

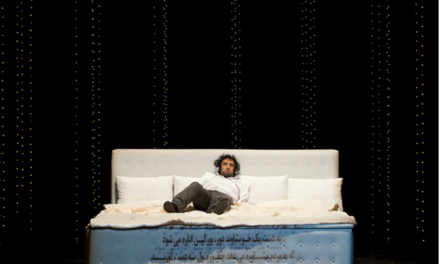

Each of the five participants comes out of the white checkered market bags–a great stage set and direction move. It plays on our objectification of migrants, referencing the inhumane ways in which those who have the wrong passport–in this case, non-EU–travel to luckier, wealthier nations. Not only do some illegal immigrants travel in market bags–others do it in coffins or fridges, it’s revealed in stories at the show. Migration is, for these people, a desperate act.

The TV show concept’s probably the play’s biggest success. The witty, entertaining, on point script, based on real stories, develop a self-contained world. It’s a different way of speaking of the awful experiences that make migrants leave their countries of origin, that they go through on the way to their new destination, and in the country, they’ve chosen to join. The script works perfectly with the minimalist set and direction.

Speaking about direct democracy through a TV show is notably smart too. Given that a TV show raised Donald Trump’s public profile, allowing him to compete for the US’s presidency, the link between politics and TV talent shows doesn’t appear tenuous at all. A political vote can be as whimsical as that on a TV show.

Molodyi Teatr

The TV show itself reflects the power game clearly–those with a British passport currently living in Britain–i.e. the “Great British Public”–decide the fates of those with a different passport living beside them. “You are your papers,” a participant in Migrants Have Talent says.

And that’s a question left totally outside the Brexit debate. The accident of “being born in the wrong place” is a massive, unspoken issue in today’s right-leaning political world. The play explores this idea, juxtaposing the month-long horrific journey of a Ukrainian girl to London–involving imprisonment, never-ending queues, and humiliation–to the easy one-day trip a British man makes to Ukraine. The difference is unjust. But then again, how a world without borders would work in practice is the subject for another show and debate.

Altogether, the performance was fresh, thoughtful and a hell of a lot of fun. Expect music and good acting too.

This article originally appeared in Central and Eastern European London review on August 20th, 2016 and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Paula Erizanu.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.