Review: Kwongkan, Perth Festival 2019

“Kwongkan” means sand in the language of the Nyoongar people, the first inhabitants of south-west Western Australia. Both Nyoongar and Indian traditional ceremonies, which are recreated in this collaboration between Australia and India, take place on the bare earth. Dancing feet connect with the sacred earth beneath.

But sand also has wider cultural significance. It appears in phrases like “putting your head in the sand”, to imply someone is ignoring the obvious or not thinking. There’s also the “sands of time” and images of sand running through an hourglass, both reminding us that time may be running out.

These themes are all too relevant when considering the urgent global challenge of climate change, explored in this world premiere performance as part of Wendy Martin’s final and stunning 2019 Perth Festival.

Through ancient dance practices, contemporary live music, aerial acrobatics, sound, video and epic theatre, Kwongkan invites us to hope for change, but more importantly, to be stirred to action.

Isha Sharvani (front) and Tao Issaro, Kate Harman, Ian Wilkes (back left to right). Photo Credit: Daniel Grant

Created and directed by Mark Howett of Ochre Contemporary Dance Productions, the production grew out of a three-year collaboration with Daksha Sheth Dance Company, who are based in the western Indian state of Kerala. Like Ochre, Daksha Seth brings together “performing artists from diverse backgrounds who seek to bridge contemporary dance and traditional dance movements.”

Howett traveled with an ensemble of artists to sacred desert lands in Australia and tropical India to create this journey from the past to the present, with a weather eye on the future. The result is not just dance theatre, but a hybrid form with strong narrative strands and a political punch.

Performed on a large, bare wooden platform overlooked by Norfolk Pines, and extending up onto the raised sloping grass behind, there is vast space available and Howett uses it well. A film screen at the back sets the tone of the work right from the start. A video (produced by Howett and associate director Tao Issaro) flashes images of bushfires, floods, polluted oceans, falling trees, and rusty cars, one after the other, demonstrating the urgency of this story of climate change and humanity’s role in it.

After the dramatic bushfire opening sequence, the three performers enter, each dancing in their own cultural style. We are led on a journey through colonization, loss, forced-forgetting, and consumption. The performers move beyond pure dance into a blend of movement, acting, and direct presentation, demanding a range of skills from each of them.

Isha Sharvani (front), Kate Harman (middle), and Ian Wilkes (back). Photo Credit: Daniel Grant

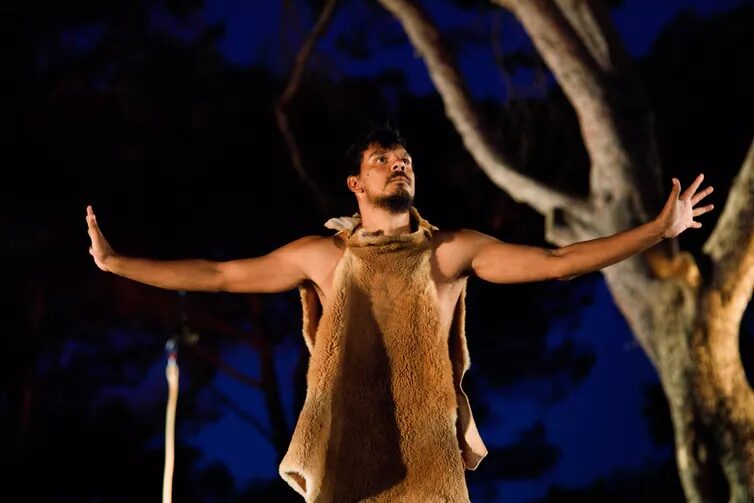

These were amply supplied by the three main dancers. Ian Wilkes, a young and very talented Nyoongar performer, is terrific. He will be known to Perth audiences through his work with Yirra Yaakin Theatre and with Ochre Contemporary Dance Productions.

Wilkes switches easily from traditional Nyoongar to contemporary dance, and on to dramatic performance. A highlight was the sequence where he became a kangaroo entangled in the barbed wire from a fence, then transformed into a man, subjugated by missionaries and forced to wear Western clothes.

Another regular Ochre performer, Kate Harmann, brings an intense emotional commitment to both the dance and the drama. When she manipulates a flimsy sheet of clear plastic, she creates beautiful yet disturbing images, ripe with metaphor.

Finally, Isha Shavani, the lead dancer of Daksha Sheth and a renowned aerialist, brought grace, precision, and strength to her performance. She is trained in various Indian dance forms such as Kathak, Chau, and Kalaripayattu, and displayed her skills in rope Mallakhamb (where acrobatic feats and poses are performed using a hanging rope). She was exceptional in the dance forms of all three cultures and is a compelling presence.

The intensity of these performances was supported by Tao Issaro’s compositions. He is Shavani’s brother, and describes himself as “a son of an artistic tribe.” He performs energetically on his drums and found objects, complementing a layered instrumental music track incorporating sounds of nature. One impressive drum is hand made from a large brass biryani pot covered with hide.

Lead dancer of Daksha Sheth, Isha Sharvani. Photo Credit: Daniel Grant

Kwongkan builds to its climax when the performers desperately try to clear the stage of a mountain of plastic. Balancing on top of an oil drum–a fitting podium if ever there was one–Wilkes uses a megaphone to urge us to get our heads out of the sand. He recalls the quote from Native American leader Chief Seattle, who watched the destruction of his country following colonization and famously said: “we can’t eat money.”

In the context of pleas from young people around the world to adults to save their future, this final sequence has a powerful impact.

It is interesting to see the epic theatre techniques of Bertolt Brecht alive and well today. Brecht used theatre to confront an audience and arouse in them the capacity to action. He wanted them to make a decision about a political issue, to question orthodoxy and become active and curious. His work aimed to awaken the audience to the realization that they can change society for the better.

We are used to being empathetic with characters on stage, but in doing so we remain detached from them and uncritical. Epic theatre aims to disrupt that state. Kwongkan takes this one step further and invites onto the stage a member of Millennium Kids, an organization that works with young people to encourage action on environmental issues.

13-year-old Bella spoke on the night I saw the performance, and pleaded with us to take action on climate change. In light of growing global movements such as School Strike 4 Climate and Extinction Rebellion, Kwongkan uses art to reflect the zeitgeist.

It begs the question: if the art we are given is not doing that, why not?

Kwongkan is playing as part of the Perth Festival until February 20.![]()

This article appeared in The Conversation on February 18, 2019, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Vivienne Glance.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.