On June 13, 2022, I spoke with Guillaume Gay, who is operational and artistic director of the French Polynesia-based La Compagnie du Caméléon. Across the Whatsapp airwaves, fifteen thousand kilometres, and the twelve hours separating Tahiti from Paris, Guillaume talked to me about Les Champignons de Paris, written by Émilie Genaedig for the company, and directed by François Bourcier. In the making since 2014 and first staged in 2016, the play is still touring in 2022. You would hardly suspect it from the birds I could hear serenely chirping in the background, but French Polynesia, as this play reveals, has been coping with the environmental and emotional wounds of the French state’s three-decade period (1966-1996) of nuclear testing on and under its soil and in its seas.

My reference to the word “blast” in the title of this article by no means intends to make light of this traumatic history, even if it does seem to chime with the irony of the play’s title, which uses a well-known appellation of mushroom (champignon de Paris) to conjure up in the mind’s eye billowing fungal-like clouds of nuclear bombs. The double meaning of “blast” though (to have a good time, and an explosion) suits the themes of euphoria, danger, and tragedy traversing the intrigue of this play. And as the phrase “blast from the past” suggests, Les Champignons de Paris is not just a lesson about a long-forgotten tragedy but, harnessing theatre’s life in the present, a lesson and talking point for the communities it plays to today.

Readers should be aware that, unless the French is indicated in brackets or quotation marks are used, the following comprises paraphrased excerpts of my conversation with Guillaume. I am very grateful to him for taking the time to talk to me about this show to me amidst the company’s busy schedule.

The Play

Les Champignons de Paris (C) La Compagnie du Caméléon.

Les Champignons de Paris is a story about plurality, based on a series of witness accounts of the thirty-year period during which the French state deployed its “overseas territory” to experiment with its nuclear weaponry. The show modestly purports to contribute a small stone to an edifice as Guillaume described to me (apporte sa petite pierre à l’édifice). Yet the pluralism of perspective also creates a fuller picture of the period in all its “monstrosity”.

“Monstrosity” because when then-President Charles De Gaulle decided to move France’s site of nuclear testing from the Sahara (following Algerian independence), a tide of “euphoria” (euphorie) swept over French Polynesian shores. This might be easy to judge from our current-day perspective knowing what we do about the dangers of radioactivity, but the installation of the French state’s Centre d’Expérimentation du Pacifique (Centre of Experimentation of the Pacific or “CEP”) brought with it job opportunities, economic prosperity, collective enrichment (Guillaume discussed how trickle-down economics actually had some success), and new cultural encounters as locals and workers (especially soldiers) from Metropolitan France crossed paths.

Les Champignons de Paris reveals, though, the “hangover from the party”: alongside the newly created discos came sanitary and environmental degradation, a mushrooming—as it were—of serious maladies related to radioactivity (including various strains of cancer). Early whistleblowers such as the poet Henri Hiro talked about the dangers that the population were quick to become aware of. Pressure also came from the French President to detonate a bomb during his visit despite unfavorable winds which blew radioactive dust back onto the inhabited regions of French Polynesia.[i]

The mechanisms of French colonialism are evident here: an assembly that had been created to accord French Polynesia was suppressed, a governor was installed and given reinforced power, the French administration tightened its institutional grip on the islands, French became the island’s lingua franca at the expense of the native Reo Tahiti, and Pouvanaa Oopa, an autonomist sympathizer and anti-nuclear voice would be sent into exile.

When I asked Guillaume about theatre’s role in “decolonizing” this history, he immediately turned me to the importance of the identity of the show’s cast members: two Polynesian actors “de souche” (literally meaning “of roots”, translatable as indigenous populations) carry the local witness accounts on which the show is based. But this is no naïve return to cultural authenticity. Les Champignons de Paris’s cast reflects the westernized transformations that took place in French Polynesian society as a result of the nuclear tests: while one of the actors comes from a mixed family, Guillaume Gay, the third actor in the show, has been in Polynesia for the past 25 years. The play also honors Tahiti’s native language, Reo—in line, coincidentally, with the United Nations Decolonization Committee’s move in 2016 to recognize Polynesian languages alongside French as the official languages of French Polynesia. Even if the play’s language is mostly French, some Reo remains untranslated, its sonority and French Polynesian society’s emphasis on oral tradition coming to the fore.

Les Champignons de Paris (C) La Compagnie du Caméléon.

However, what Les Champignons de Paris also touches are a series of silenced uncomfortable truths, most notably the will (volonté) on the part of islanders to adapt to the new Zeitgeist brought about by nuclear testing: French, for instance, was embraced because it was perceived as the language of economic and cultural success. The play hits a nerve for this reason: Guillaume emphasized to me the collective guilt and shame, the feeling that locals “sold out” (se sont laissés acheter) to French colonial interests. This guilt combined with institutionalized silencing—the éducation nationale is only just beginning to broach the subject in its curricula—have made this environmental and social tragedy a taboo topic.

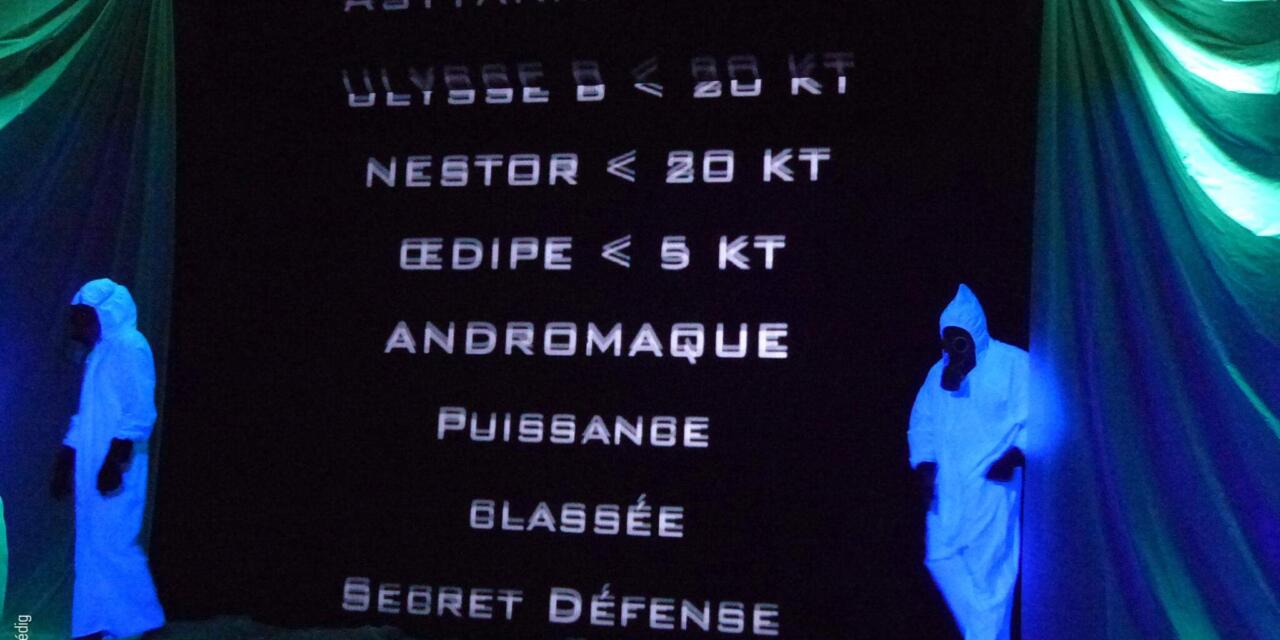

Theatre, though, has always boasted of a cogent capacity to undo taboo. The cast wear organic paint that progressively becomes visible to spectators with a change in lighting, a visual language conveying the silenced but sure presence of radioactivity in the air, ground, and bodies of French Polynesians. Les Champignons de Paris has also returned to theatre’s original premise as agora or forum, galvanizing spectator response in the effort to move on from past wounds.

Audience Response

Les Champignons de Paris (C) La Compagnie du Caméléon.

The Compagnie du Caméléon is no stranger to socially engaged theatre, running workshops to encourage younger generations into the visual and performing arts, and broaching subjects such as homelessness, disability, foster care, gender inequality, and the sexual abuse of minors. These topics are never closed down as the final curtain descends. Similarly, Les Champignons de Paris, as Guillaume put it, is a “prelude” or “pretext for a debate” (prétexte au debat). Each performance is followed by a collective conversation with the audience, a much-needed salve to the decades-long discursive lead weight (chape de plomb) imposed on French Polynesians.

It is somewhat of a pop-psychological truism, but “blasts from the past” will never be healed unless the devastation and pain wrought in their wake are fully acknowledged. And the success of Les Champignons de Paris among local audiences demonstrates the need for a talking cure. With the show’s first fifty or sixty performances, over 95% of audience members were indigenous French Polynesians—a stark change from the whiter, more homogeneous, audiences that other shows in the company’s repertoire have tended to attract. More than a book or a scholarly article, theatre has proven true to its history as a popular medium as well as a construction site for citizenry.

That said, “blaming” guilty parties is avowedly not on offer in this show, neither in these discussions nor in its intrigue. As Guillaume made clear to me, the average Metropolitan French citizen is no more responsible for devastation of French nuclear policy than local Polynesians who complied with what they thought would be the dawn of a prosperous era. Steadfast in its adherence to the French tradition of universalism, the show seeks to tell a collective history where everyone finds their (albeit differentiated) place, rather than finger-pointing at individual identity groups. This perhaps explains the show’s success in mainland France too, where it has played to audiences in Avignon and the Paris region, and has never once encountered hostility despite the history of colonialism that might weigh heavy in the minds of white people here. One woman in this context even recognized her father, who had worked in French Polynesia, in one of the archival photographs projected in the show.

Some people might accuse the French attachment to universalism of a certain idealism, but Les Champignons de Paris’s resonance in other former colonies of the French-speaking world complicate this assumption. The play has also proved a powerful talking point for audiences in the French Caribbean. In Martinique and Guadeloupe, the play’s nuclear plot found an obvious echo in the use, banning, and then reintroduction of the noxious pesticide chlordecone. Guillaume regaled me with the anecdote of one performance in Guadeloupe that ended with the audience chanting, at high-decibel volume, “Respect”.

I evoked the notion of catharsis in closing our conversation, and Guillaume confirmed that emotional purging is what the company aims at in audience members. The road though has not always been smooth. He described to me the play’s one “misadventure” (mésaventure) with local audience at a former aerial base of the Centre d’Expérimentation du Pacifique. The ring-shaped “atoll” (an island shape characterizing French Polynesia) had witnessed an overnight transformation with the arrival of between three and five thousand technicians, soldiers, and other workers connected with the nuclear industry. Euphoria would seem to be the way audiences had perceived the three decades of testing in this location, and locals had the impression that Les Champignons de Paris was there as the proverbial party-pooper. Even in this setting though, the play proved a spur to disclosure, albeit sheepishly. While most audience members deserted the after-show debate, several of them came to talk to the cast members in the village square the next day, to share their accounts individually.

The show’s reminder not to judge or remove oneself from histories that seem far away, geographically or temporally, seems truer than ever. In Europe, a summer of successive heat waves and nuclear threats is drawing to a close. And Les Champignons de Paris seems to me an alarmingly prescient “blast from the past” for our current moment here.

[i] According to historian Frank Zelko, De Gaulle was irate about the postponing of the nuclear testing because of strong easterly winds at the Centre d’Expérimentation du Pacifique off of the atoll of Moruroa, used by the French Centre d’Expérimentation du Pacifique as testing ground. The CEP had promised to detonate only on days when the winds were westerly so that radiation would diffuse across uninhabited regions of the Pacific. But because of De Gaulle’s impatience, they detonated the weapon on 11 September, 1966, “sending a cloud of radiation blowback across the South Pacific” (114). Frank Zelko, Make It Green Peace! The Rise of a Countercultural Environmentalism. Oxford: OUP, 2013.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Lara Cox.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.