‘If this were a text for the theatre, here is how it would begin’ – these are the opening words of the French literary superstar Édouard Louis’s third book Who Killed My Father, published in 2018. It is no wonder therefore that this prose piece that takes on the combined form of a letter, memoir, and an indictment of the French ruling class, has already been staged at least three times in the year 2022: in a production directed by Nora Wardell at the Tron Theatre in Glasgow; in a co-production between Berlin’s Schaubühne and Théâtre de la Ville in Paris directed by Thomas Ostermeier and performed by the author himself; and in this adaptation by Belgian director Ivo van Hove, performed by Hans Kesting and co-produced by the International Theatre Amsterdam and the Young Vic in London.

The author’s stage directions, functioning as a metaphor-laden preface to the narrative written entirely in the second person, prescribes that the two characters stand in the same space together whereby they however cannot touch each other, and only one (the son) speaks which ‘does violence to them both’. This suggested form reflects the content of the story about one family’s struggles to overcome a history of violence, homophobia, illness and destitution in search of love, acceptance and understanding.

In a way that we have come to expect from Van Hove, he simultaneously honours and meaningfully defies the author’s prescription in his staging choices. Kesting, the Dutch actor for whom Van Hove specifically intended this adaptation, displays a depth of sensitivity, a power of instant depiction and, crucially, he is the age Louis’s father could have been when he died. Contrarily and perhaps complementarily to Ostermeier’s choice to cast the author in his solo show, in Van Hove’s monologue version multiple characters are potentially contained in the actor’s physical presence: the son whose lines he speaks, the father whose psychophysical space he engenders, and the mother whose occasional voice and manner are conjured up into the peripheral vision of the piece too. Additionally, Kesting is a great dancer which comes in handy at a key moment of captivating the audience’s attention.

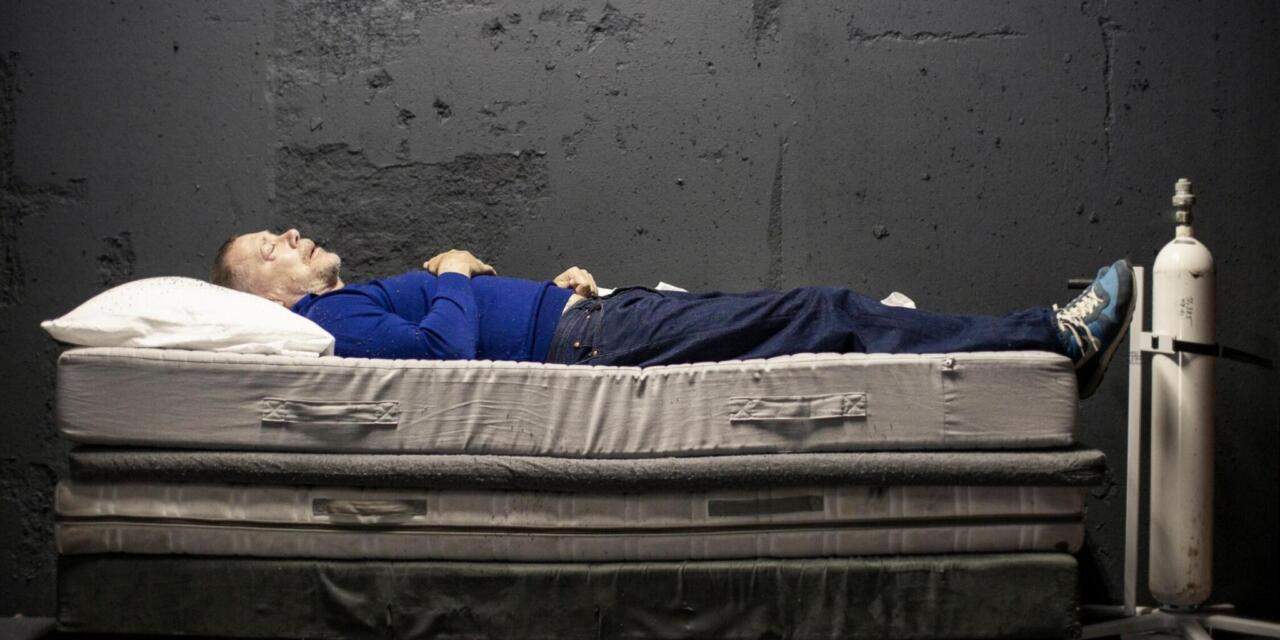

Hans Kesting in “Who Killed My Father.” © Jan Versweyveld

Van Hove’s regular designer collaborator Jan Versweyveld provides the decidedly sombre set and lighting for this show. The engulfing smoke is not only an omen or an atmospheric tool but also a necessary ingredient aiding the characterisation of the father who is a smoker that sleeps (on a bedspread of ash) with an oxygen bottle. As is to be expected in a working class household that conveys the ecology of Louis’s narrative, a TV has a central place in an otherwise sparely furnished room. And there are dents in the wall as obligatory documents of anger. Moments of respite from the gloom are provided courtesy of the iconic and uplifting citations of the 1990s popular culture forming part of the temporal context of the piece.

Van Hove’s adaptation of the text lacks a traditional dramaturgical arc. Structurally it is a diptych focusing in the first part on memories of childhood and in the second on the disenfranchisement of the French working class. However, Kesting makes this hold together. ‘The ruling class in general considers politics a question of aesthetics’ is an aphoristic key line at the centre of the piece that just about falls short of its potential to be folded in as a metatheatrical consideration. Instead, Van Hove as an adaptor goes for the Brechtian promise of an upbeat finale to send the audience up on its feet.

Overall it is a strong and solid production served expertly by the joint forces of the stellar cross-European author-actor-designer-director team. Inevitably it raises relevant and complex questions too in Britain only recently divorced from the rest of Europe but teetering on the brink of a very likely poverty crisis this winter.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Duška Radosavljević.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.