“Time means nothing. That is, it does, but not in the way we think,” says Joseph, the protagonist of the play “Ask Joseph,” by Slava Stepnov and Roman Freud. He tries to explain to his wife that their love is not dead and gone but nearby, at arm’s length and, paradoxically, off limits at the same time. “Do you remember,” Joseph asks, “how you and I used to sit in that ridiculous bar and look at each other? That did not go away either, it was just in a different time.”

In the twenty-first century, after many decades of totalitarian rule, shifting regimes and ideologies, and now, during the cruel war in Ukraine, we, Russians, are still looking for our home, some kind of Russia (not synonymous with the Russian Federation)—a place that “did not go away,” but hopefully, is patiently waiting for us “in a different time.” This place will become our new home, wherever we are—Russia, Europe, America. Together, in this home, our memory and culture will settle down.

Slava Stepnov at the 2018 Saransk Theater Festival, Saransk, Russia.

These thoughts occurred to me in 2018, after watching the premiere of “Ask Joseph” (directed by Slava Stepnov)—a mosaic narrative that includes biographical facts about Joseph Brodsky, the Russian-American poet, Nobel Prize laureate in literature, with quotes from his essays and interviews, and imaginary scenes from his life intertwined with fragments of Chekhov’s “The Seagull”—at New York City’s STEPS Theatre. For several years now, I have been following the work of STEPS, a multilingual theater company of Russian origin in America, and I consider it one of the most prominent Russian theater groups outside Russia. At any rate, it is a company that creates serious art with profound meaning, theater that confidently exists in a “different time” and occupies a place that “did not go away,” as its own place and home.

My acquaintance with STEPS Theatre began in Montreal in 2016 when I saw their touring production of “Vasily + Federico,” based on stories by Vasily Shukshin. It was a highly unusual show—cinematically spectacular, vivid, and simultaneously philosophically profound. By imagining Russian folk drama, Shukshin’s “Heart of the Mother,” in the sophisticated Italian stylistics of Fellini’s “8 1/2,” STEPS revealed the Russian in the universal and the universal in the Russian. With this dualism, STEPS struck and fascinated me.

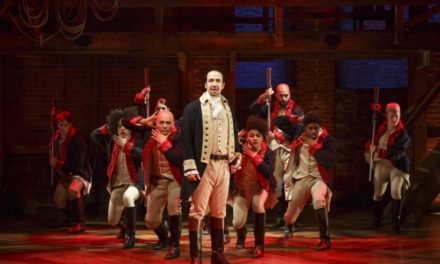

Left to right: Mother (Elena Stroganova) and Father (David Varer) in the 2018 2018 STEPS Theatre’s production of Slava Stepnov and and Roman Freud’s “Ask Joseph,” New York.

In the play and performance of “Ask Joseph,” Stepnov and his co-writer and lead performer Roman Freud, present the Russian and the universal not in harmony, but in more complex relationships and circumstances: in conflict, in time, in space, within a single soul. The focus of the stage space in “Ask Joseph” (scenographer Viktor Pushkin) is a multipurpose table, serving as a kitchen counter, work desk, meeting and feast table, at which and around which gather the characters of the play—Joseph (Roman Freud), Mother (Elena Stroganova), Father (David Varer), Actor (Misha Freud), Actress (Lisa Kaymin), Yakov (Sergey Nagorny). This table is a metaphor of home, family, society and all the entailed everyday routines. Strangely enough, however, wherever the events take place—Leningrad, in exile, America—only Joseph, an essential outcast, feels at home at this table. The others seem to be homeless—confused and disoriented in their own homes and within their souls. Only Joseph, who has learned to inhabit every corner of space, can see himself and the world around him for what they are. “I may be a failed Jew and not a Christian or anything else… But whether I am a coward, whether I have enough strength not to compromise, how much good I can do to others—that’s what really matters to me.” People do not understand this poet, who also exists in a “different time,” a temporal dimension of his soul, not its external chronology. This is the only time that matters to Joseph. But to the outside observer, Joseph’s life is, at best, “fate,” and at worst, “chaos.” Joseph seems to be anachronistic, but the play and performance hint at the possibility of synchronizing our lives with his, learning from him. The possibility, even the imperative, is contained in the title of the play, to “ask Joseph.” Language plays a critical role in such a dialogue. In a world where people, like the builders of the Tower of Babel, have forgotten how to call things by their names, only Joseph can restore the connection of these words and their meanings, in order to remember the “true” language. Emphasizing this role of the poet, one of the characters in the play turns to Joseph says, “We shall call you, say, Language.”

Left to right: Slava Stepnov, Elena Stroganova, and Misha Freud at the rehearsal of the 2018 STEPS Theatre production of “Passions for Mikhail,” New York.

“Ask Joseph” and other works by the STEPS Theatre—“Vasily + Federico,” “Passions for Mikhail,” and “Flawed Choir”—focus on both creativity and creators. Thus, STEPS Theatre provides a space—between the stage and audience, beyond time and place—for meaningful dialogue with Joseph Brodsky, Federico Fellini, Vasily Shukshin, Mikhail Bulgakov, and Anton Chekhov. In 1997, STEPS opened in New York with a production of Chekhov’s “The Seagull.” In 2022, in the theater’s latest premiere, “Flawed Choir,” based on Stepnov’s play and directed by the author, STEPS returns not only to a conversation with Chekhov, but also—on a new level—tackles the dualism of the Russian and the universal.

Left to right: Zulla (Elena Che) and Iraklii (Timothy Kompanchenko) in the 2022 STEPS Theatre’s production of Slava Stepnov’s “Flawed Choir,” New York.

Stepnov’s plot is Chekhovian: uneventful but with a twist. Four Russian émigré actors—Adelaida (played by Yelena Stroganova), Roosevelt a.k.a. Rodion (Kostiantyn Mishchenko), Zulla (Elena Che), and Iraklii (Timothy Kompanchenko)—meet at a Russian radio studio in New York’s Brighton Beach to record commercials. The characters seem to complement (sometimes, even to complete) the story arcs of Chekhov’s characters by adding possible behind-the-scenes episodes and connecting different characters across the plays. Unlike Chekhov’s context—Russia—the context of the “Flawed Choir” is Brighton Beach, “Little Russia” or Russian America. Adelaida, Zulla, Roosevelt, and Iraklii are emigrants and immigrants—unsuccessful ones. Feelings of displacement, loneliness, alienation, uprootedness, and liminality are common to most immigrants and hence universal. The “Flawed Choir” digs deeper, to unearth the Russian dimension of these complex phenomena. A permanent state of uprootedness—the endless and aimless movement of the Troyka Rus, sung by Nikolai Gogol—is presented here as an inescapable and even natural state of the Russian soul. In this play, like in “Ask Joseph,” language is imagined as a cultural compass that allows for finally finding a place and time: a home instead of a liminal space, a meaningful continuity instead of endless and aimless history. But language must be found first. In the meantime, in the play’s finale, the actors can only silently imitate a chorus, singing a song together but without words.

After 25 years of work, more work lies ahead for the STEPS Theatre. STEPS has much more to say to the audience, and there are many more questions to “ask Joseph” (as well as Vasily, Federico, Anton, Mikhail and others). There are more lessons to teach and to learn (in addition to the lessons of Joseph Brodsky, who became a great Russian poet only after he left Russia). Paradoxically, it is the artistic dualism of the Russian in the universal and the universal in the Russian, that makes STEPS’ work coherent and consistent. STEPS exists organically in its global cultural, linguistic, and artistic context. Therefore, as a Russian theater, STEPS can gain a new perspective, set new tasks, develop a new language, and even, like Joseph, become the language of that Russian culture that exists beyond time and place.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Vassili Schedrin.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.