It begins “How does a bastard, orphan, son of a whore/And a Scotsman/ dropped in the middle of a forgotten spot in the Caribbean by providence impoverished,/In squalor, grow up to be a hero and a scholar?” It’s a good question, and the rest of the musical Hamilton–all three glorious hours of it–offers many answers.

A similar question might be asked of the show itself, which began with startlingly unpromising materials. How does the story of an 18th-century American statesman, an elitist quasi-monarchist, and a federalist, all but forgotten, left out of most popular American histories, set to rap and hip-hop and performed by a nearly all non-white cast, become a global phenomenon? Now that it has come to the UK at last, after three smash-hit years moving from off-Broadway to Broadway to Chicago to San Francisco–heading west, in good American fashion–British audiences can now find out for themselves.

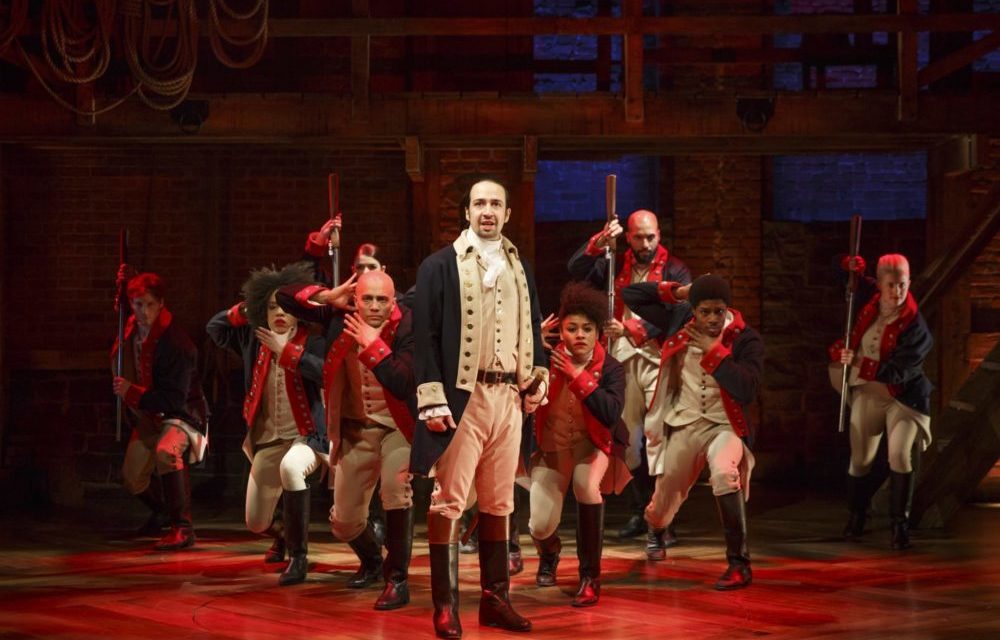

Although the story of Alexander Hamilton is complex, the answer to the question of why it has become a smash hit is simple: Lin-Manuel Miranda, the man who wrote the music, the lyrics, the book (i.e. the play), and starred in the show for two years in New York before handing off to a new cast at the end of 2016, is, as the evidence of his staggeringly brilliant show makes clear, a genius, of the stone-cold variety.

The West End version of Hamilton with Rachelle Ann Go (Eliza Hamilton) and Jamael Westman (Alexander Hamilton) (Photo by Matthew Murphy)

Miranda’s accomplishment has brought comparisons to the titans of American musical theatre that may sound extravagant–Rodgers and Hammerstein, Leonard Bernstein, Stephen Sondheim. But none of those composers also starred in their shows: not only does he deserve to be in their company, he has done them all one better.

Miranda was not the strongest singer in the show’s original cast, as he is the first to admit–and he is a markedly generous composer, giving many of the best songs to voices bigger than his own–but his stage presence is immense. I had the pleasure of seeing most of the original cast on Broadway in New York in June 2016: it was the night of the EU referendum, and my British husband and I emerged from a musical about debates over federalism, independence, and sovereignty into the news of Brexit.

But the topicality of the show was always unmistakable: Miranda saw in Hamilton’s story parallels with the political situation today. Hamilton was an immigrant, an illegitimate orphan from the West Indies whose intellectual potential was so clear to his neighbors that they pooled together to send him to university in America.

circa 1790: American statesman Alexander Hamilton (1757 – 1804), principal author of The Federalist collection of writings. An engraving after the original painting by Chappel. (Photo by Hulton Archive)

He arrived in 1772, at the age of just fifteen, as the revolutionary spirit was starting to sweep the colonies. That revolutionary spirit is also what drives the show, reminding Americans in a time of xenophobia and growing nativism that the United States has always been a nation of immigrants and strivers, offering a call to democratic meritocracy.

Hamilton became a general in the Revolutionary War (as Americans always call it, never the “War for Independence”) before becoming George Washington’s right-hand man and the nation’s first Secretary of the Treasury. But it is also a dramatic story of the rise and fall in the vein of classical tragedy: Hamilton self-destructed politically, and was killed in a duel by the then Vice President, Aaron Burr, aged 47.

Part of the reason why the show has been such a phenomenon in the US is that Hamilton was the forgotten Founding Father. Most of the nation’s other framers–those who wrote the founding documents, including not only the Declaration Of Independence and the Constitution, but also the Federalist Papers, which were written by Hamilton, James Madison and John Jay to promote the ratification of the Constitution (Hamilton wrote 51 of the 85 articles) – went on to become president, and have had institutions, buildings, and streets named after them, literally absorbed into the fabric of the nation.

There is not an American alive who doesn’t know that George Washington was the first president, or that Thomas Jefferson wrote the Declaration of Independence. But Hamilton never became president, and although his arguments for federalism, the banking system, and the national debt hugely influenced the course of American history, that history has tended to marginalize or even edit him out altogether.

“Enter – me!” as Miranda’s Hamilton sings near the beginning of the show: Hamilton the musical is a conscious act of national myth-making, returning Hamilton to the pantheon of American “founding fathers.” In so doing, Miranda whitewashes some of Hamilton’s story, not only simplifying in the interests of storytelling (dispensing with six of his seven children, for example, and rearranging the chronological order of certain events) but also eliminating some of Hamilton’s less sympathetic qualities.

The musical’s Hamilton is opposed to slavery; the historical Hamilton engaged in slave-trading and was inconsistent at best in his written attitude to manumission. He was also a monarchist in all but name, arguing for a president for life, while the musical’s Hamilton is an ardent democrat. Although he grew up in poverty, Hamilton was no populist. His suppression of the Whiskey Rebellion of 1791–an uprising against an unpopular tax–does not make it into Miranda’s tale. But although its image of Hamilton is sanitized and modernized, even somewhat idealized, the musical is not hagiographic. Its Hamilton is a complex, impulsive, brilliant man who makes mistakes but also leads by example, and inspires.

Questions have been asked about how this very American musical will go over in Britain. Those questions are presumably only asked by people who haven’t seen it or have never met a British person. Hamilton is a work of such heart-shaking brilliance that it transcends petty concerns. People who hate musicals love Hamilton. People who have no interest in American history are fascinated by Hamilton. It is exhilarating, dazzling, superlative: and in the end, questions of history and politics, nationality and myth-making, are beside the point. The point is simple: Hamilton will blow your mind.

This post originally appeared in iNews on December 18, 2017, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Sarah Churchwell.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.