One of the most vivid memories of my childhood is sitting on the ground in a parking lot of my Lower-Silesian hometown, mesmerized by vivid, fantastical figures hovering above the ground on stilts. Every year for a few days, parking lots, streets, and, most of all, the city’s main square would turn into a theatrical stage brimming with the liveness of theatre. As a kid and then young adult, I definitely approached it predominantly through the senses–I remember it by the scent of colorful smoke coming up from the flares, the sight and warmth of fire, the touch of the cold ground under my palms. I don’t really remember the stories being told, but I do recall the thrill of seeing foreign troupes animating the crowds of city-dwellers and injecting color into the grayness of the public space, usually just coated with the routine of everyday life. And so with great pleasure, I came back to the 36th edition of the International Street Theatre Festival (Międzynarodowy Festiwal Teatrów Ulicznych – MFTU) in Jelenia Góra, to experience it once again and to see whether the allure of this genre is still equally as enthralling as in my childhood. However, now as an adult and an academic, I couldn’t help but think about the ways in which the stories are told and wonder what happens to the actual “word” when it is transferred to the street: whether it secures a thread of understanding between artists and spectators, or cuts right through it? Street artists often choose to evade spoken words in favor of nonverbal communication, which is meant to be more inclusive, making theatre accessible for wider audiences. In street theatre, the word is fickle, and at times even uninvited. Wondering whether words are needed at all, whether the gestures are enough and whether street theatre is able to reach that utopian universal intelligibility, I paid special attention to productions that bypassed spatial limitations and put emphasis on reaching out to wider audiences.

This aspect of balancing out a hierarchically uneven relationship between stage and audience is at the core of the genre. What is known today as street theatre has its roots in rebellion and was always fond of solutions that would take down conventional power dynamics. Bringing down authorities of all kinds, including the authority of text, was often a driving force behind modern outdoor theatre. It grew out of the experimental theatrical creation of the 1960s, and the turmoil of the year 1968 allowed theatre to go beyond its conventional frames. At that time, performing outside the confines of a building was associated with political acts of reclaiming spaces and reviving communities. Experimental theatres across Europe and the Americas took performance to the streets, in the utopian pursuit of breaking down the dividing (fourth) walls and creating a community of active spect-actors.

In contemporary scholarship, street theatre is treated more like an illegitimate child of the progressive theatrical “high art.” It remains largely understudied, often ignored and criticized for being a form of entertainment for the masses, with its gimmicky productions, acrobatic stunts, and clownery. However, the often-downplayed but crucial dimension of street theatre is the aspect of attempting to bring down barriers. Whether it be language, access, or interest, street theatre delivers different solutions for ever-present obstacles and limits.

Speaking of obstacles, the MFTU in Jelenia Góra itself was founded in 1983, in the harsh times of Communism, when Poland was still under martial law. Alina Obidniak, a director of the city’s Norwid Theatre, and also – fun fact!–a close friend of Jerzy Grotowski, started the very first street theatre festival in Eastern Europe right here, in an inconspicuous valley town of South Western Poland. Neither rationed food nor fuel by tokens discouraged artists from across Europe from coming here and injecting a brand new dynamic into the dull everyday life of the communist era. Fast forward to July 2018: the MFTU is still alive, even though its funding dwindles year after year. Nevertheless, in its 36-year tradition, it is now a staple and an absolute hit among both the city’s inhabitants and its visitors. Among the invited productions, both the Theatre of the Eighth Day, a Polish street theatre veteran, and the Dutch Theater Gajes chose to spatially engage with their audiences. Curiously, while the former chose to nix spoken text altogether, the latter confronted the audience with an abundant mix of language(s). Both troupes provided very different answers to the question of whether language stands in opposition to universal intelligibility and accessibility.

On being understood

One of the pioneers of Polish street theatre–the legendary Theatre of the Eighth Day–was the opening act on the first day of the festival. Summit 2.0 was a story about power broadly defined. I say broadly because depending on whether one read the description of the performance beforehand in the program or not, the reference point for “power” could differ, but we will get to that later. The story develops between a few characters moving around the crowd on tall, wheeled platforms. There is a feast, and oh it’s fancy! The costumes, makeup, and the general monumental presence of the actors is absolutely hypnotizing and works perfectly well as a device to palpably convey different aspects of inequality. The message is very clear and political, and so are the images that draw on Bunuelian classics. Right in the shared space of the central city square, a bunch of privileged individuals dominates–and here, quite literally–the mob below them. Standing above the crowd, as if also, in some sense, above the law, the characters excite the masses with bread and circuses, throwing glitter off their platforms and reveling. They are the ones that are free to move, as the crowd below can only shuffle around according to the movement of the platforms, often trying to escape the unstoppable motion of these giant contraptions. Soon the tables turn; the group of ignoble characters is infiltrated by “outsiders” and then overthrown by the youths who rebel against them.

Summit 2.0, Teatr Ósmego Dnia [Theatre of the Eighth Day]. Photo by Tomasz Raczyński, and reproduced with permission.

On finding home

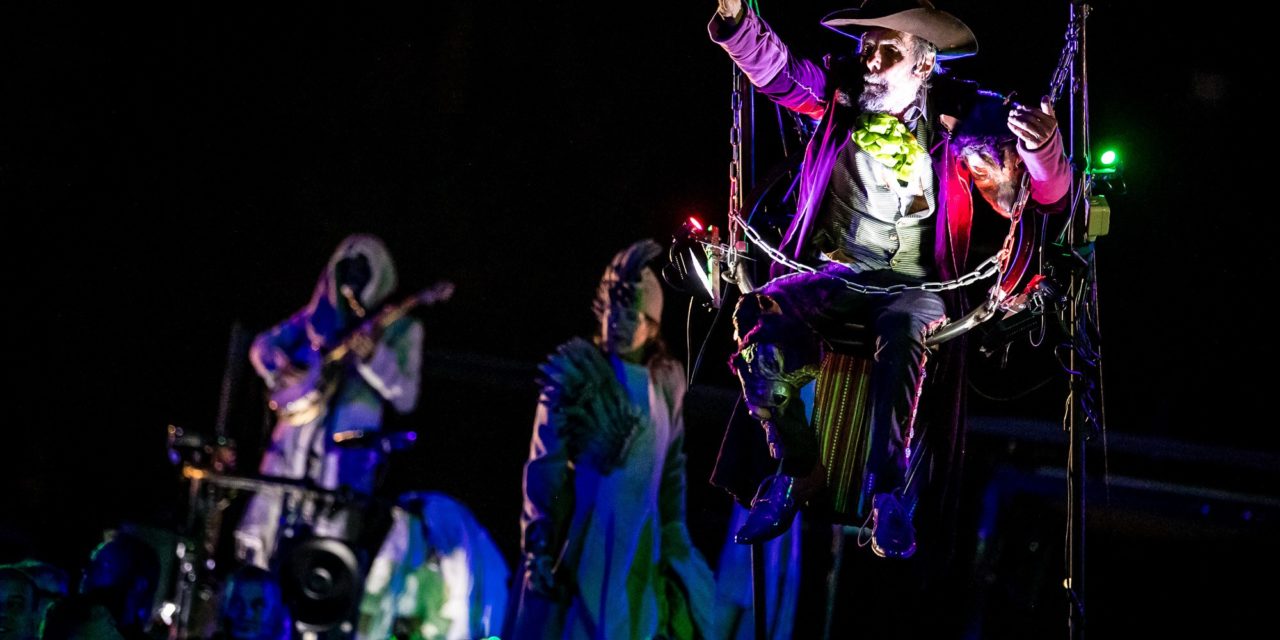

In the act closing this year’s edition of the festival, the Dutch Theater Gajes delivered their take on Homer’s Odyssey. Here the war hero’s journey home takes place on a remote parking lot in the city, packed to the brim with spectators. It begins with live music and a voice-over in Polish which later occasionally comes back throughout, providing a general narrative. The artists establish a connection with their audience in the very first scene, when Odysseus’ crew jumps off a platform, disbanding and scattering among startled spectators. The story unfolds not so much in front of its audience but above, around, and among it. Heads need to turn frequently; characters on stilts often jump out from inconspicuous corners of the lot. The spectators had better be alert: there is occasional beer-spilling, vegetable-chopping, and water coming out from underneath the protagonist’s boat, which is sailing above the crowd. Words coming to life, lines of text reimagined, draw the story of Odysseus in 4D, keeping its audience on its toes.

The Odyssey, Theater Gajes. Photo by Tomasz Raczyński and reproduced with permission.

In addition to bringing the story of Odysseus to the street, the troupe also seemed to be testing the functionality of words in a setting that is much more communal and open than a conventional theatre. This is an especially challenging quest, in view of the fact that Odysseus’ boat sails on foreign waters, and in this particular voyage, the Dutch actors are engaging with a Polish audience. The choice to rely on a widely known story is already one that puts accessibility above all other factors. We begin on the same page; we either know the story quite well or we have heard about some elements of it–sirens, Cyclopes, and so on. So how do the words appear there? Does the language succeed in landing on the street and staying accessible to the audience, even if the spoken words are–more often than not–foreign? Most of the dialogue is spoken in English, though there are some moments of Dutch, sparkles of Polish phrases and the voice-over; but above all, this monumental spectacle is self-explanatory in its form, no translation necessary. Of course, something to keep in mind is that often street theatre, while putting emphasis on being universally understood, paints the characters in rather broad strokes. Nevertheless, Gajes manages to somehow find the right balance.

The Odyssey, Theater Gajes. Photo by Tomasz Raczyński and reproduced with permission.

There is Odysseus, who is downright verbose, and for that, we cannot really place blame anywhere (apart from Homer, obviously), but it also seems that his dramatic quest is conveyed equally well through other devices in the performance. There is Penelope, as quiet as one would expect her to be, followed by Athena, who is laconic but precise and powerful in her language. Then there is Poseidon, who is able to move around using a Polish phrase (z drogi!/get out of the way!), and that’s basically all one should know about him, as he already exudes straight-up badassery riding on his ridiculous car. There is also Poly-famous (sic), chopping veggies as easily as he splices different languages in his song, and even though he does not, after all, speak a word in Polish, he can ultimately be forgiven, as his mélange of gibberish, French, German, and Dutch goes quite well with the Cyclops’ swagger and whimsicality. In short, the language being used is a supplement to what is already there. On the other hand, however, this strange mix of different languages–with Polish words serving as floating lifebuoys–paints a beautiful and universal image of a tricky journey home, with a backdrop of trials, tribulations, and linguistic misunderstandings, a story that many audience members can relate to. It is one of those performances that leave you with your jaw dropped and eyes watered. You suddenly become immersed in a community of strangers; you cherish some moments of togetherness with them; you get touched by music (or by a bike-like platform with a musician on it that just happens to roll past), by words you might not understand, by water flowing from underneath Odysseus, by Homer’s story that you almost forgot from your college years. Literature and theatre merge seamlessly, on the street, served in a wordy but somehow intelligible and accessible package.

The Odyssey, Theater Gajes. Photo by Tomasz Raczyński and reproduced with permission.

Wordy or wordless, street theatre continues to have a manifest and significant presence in the lives of many towns across Europe. It manages to be intelligible, accessible, and enthralling, bringing performances to older and younger generations, bewitching them and biting them with the theatre bug, just like I was years ago.

The Odyssey, Theater Gajes. Photo by Tomasz Raczyński and reproduced with permission.

Agata Tumiłowicz-Mazur is a scholar, translator and occasional theatre critic. She is currently pursuing her PhD in Comparative Literature at New York University, where she is writing a dissertation on archive and performance. She received her BA in Romance Languages (French and Spanish) from City University of New York. A couple of years later, she became more of a nomad, living and writing in Paris, Warsaw and Prague. Currently she is a fellow at NYU Prague. She has a secret love for street theatre.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Agata Tumiłowicz-Mazur.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.