As part of the China Focus Events Series, the British Library, in collaboration with Sinolink Productions, hosted a series of short performances by the internationally acclaimed China National Peking Opera Company (Guojia jingju yuan), which has now become a habitué of the London autumn theatrical season.

The shows were held in the afternoon of October 13 and 14 and consisted of the staging of individual sections from four Peking Opera plays: The Crossroads Inn, Fairy Sending Blossoms To Earth, Empty Fort Strategy and the popular tragedy Farewell My Concubine. All scenes were briefly introduced by Kathy Hall—who is a London-based renowned practitioner of Beijing and Kun Opera—and carried Chinese and English surtitles.

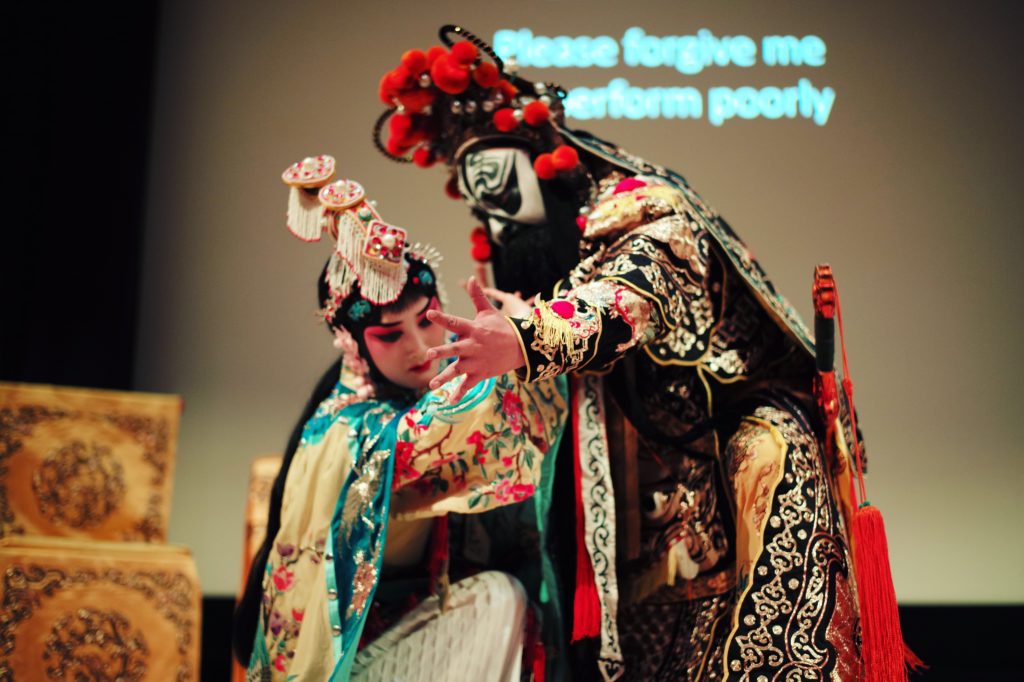

The choice of plays provided an excellent opportunity for the audience to see a combination of both civilian (wen) and martial (wu) scenes, and, most importantly, to have a taste of the supreme expressiveness of traditional Chinese theatre. Through a rich blend of interconnected elements, such as multi-colored costumes, color-coded face paints, musical accompaniment, a skillful use of verbal language and a highly stylized, aesthetically pleasing corporeality, Peking Opera actors are able to capture the audience’s imagination and to transform an empty or quasi-empty stage into a dazzling new world.

In The Crossroads Inn, two male characters (played by Haoqing Wang and Bo Liu) performed a combat scene in the dark, spiced up with humor. As the stage was brightly lit up, the actors were extremely dexterous in miming a pitch-dark setting. The audience was amused by the frequent episodes of dramatic irony, by a whole array of comical facial expressions and by a set of awkward–sometimes mutually synchronised–movements, which were meant to portray the characters’ individual frustrations at not managing to find each other in the dark. At other times, the action became breathtaking and the tension increased dramatically as the characters nearly hit or cut each other’s limbs. The musical accompaniment, which consisted mainly of percussions, helped create a dimension of intermittent suspense while punctuating rhythmically the performers’ gestures, steps, grimaces, and changes in mood or direction. Possibly as a result of the synergy between the kaleidoscopic costumes and the perfect synchronicity of music and actions, this combat scene soon grew into a kind of dance. This confirmed the idea that, as Peking Opera star Mei Lanfang (1894-1961) once stated, the main objective of classical Chinese theatre is to create a sense of aesthetic beauty for the audience. Yet, realism was not missed. For example, when a character was hurt, his reaction was more than eloquent and all his facial muscles were grotesquely contorted to convey the idea of physical pain.

Peking Opera at the British Library (Credits: JUZIARTS)

Fairy Sending Blossoms To Earth was a combination of music, singing, and dancing. Here, the audience could really perceive the pictorial potency of classical Chinese performance and its close relation to the visual arts. The actress playing this solo performance (Zhongyu Dai) executed a delightful dance, during which she moved around the stage while swinging two 12-metre long silk ribbons as a means of creating a sense of heavenly enchantment. Part of Mei Lanfang’s earliest experiments in modern Peking Opera, this piece is particularly commendable for its choreographic representation of a Buddhist tale and for having drawn inspiration from a Buddhist wall painting from Dunhuang, a city in Western China, along the silk road.

Empty Fort Strategy featured a sung monologue performed by a laosheng character (old man; played by Lei Liu) representing the military strategist Zhuge Liang who employed the titular “empty fort strategy” as a means of inducing the enemy to retreat. Here, the audience could have a taste of a male voice singing in slow metre.

The last performance was a well-known scene from the heart-breaking finale of Farewell My Concubine, featuring a jing (male painted face role; played by Jiaqing Wei) and a wudan (woman warrior; played by Hong Zhu). Set against a warfare scenario, this highlight zoomed in on the relationship between the historical figures of King Xiang Yu and his favourite Yu Ji, who accompanied him on his military campaign, offering advice and emotional comfort. The actors were excellent in portraying all the nuances of this emotionally charged scene. Particularly noteworthy was the contrast between the sturdy but prostrate king and the physically delicate yet internally resilient concubine. The real highlight of this scene is a lengthy sword dance, which the concubine executes in order to cheer up her distraught consort. Contrary to any expectations, this does not involve formidable martial arts acrobatics but is more apt to convey an idea of feminine grace and agile sword handling. The tension rose again, unrelentingly and steadfastly, when the concubine tried hard to snatch the king’s sword with which she would eventually cut her throat. Her efforts and the king’s attempts to elude them came across as yet another dance. A remarkable aspect of this scene is also the appearance, on stage, of the king’s horse, which was symbolised by a large riding crop held by a soldier who accurately pantomimed the horse’s movements.

Peking Opera at the British Library: Farewell My Concubine (Credits: JUZIARTS)

Historically, the aural dimension of classical Chinese theatre (including Peking Opera) has been prominent in determining the appreciation of domestic playgoers, to the extent that going to the theatre is termed ting xi in Chinese (to listen—ting—to a play—xi). However, when Peking Opera started to tour abroad in the 1920s-1930s, the visual impact of this type of performance was ingeniously amplified in order to appeal to non-Chinese spectators and to enhance its purported exoticness.

In a similar way, the highlights performed at the British Library were put together to draw attention to what theatre director and theorist Huang Zuolin once called “the outgoing techniques of representation” of the Chinese actor, with reference to Mei Lanfang, who founded the China National Peking Opera Company in 1955. Capitalising on the variety of artistic skills mastered by the actors of the company, these scenes exhibited the externally antinaturalistic approach to the theatrical performance as suggested by the terms biaoyan—which means “to perform” but whose literal meaning is “to manifest and display”—and xieyi. The latter term, which belongs to the realm of ink painting and means “to portray the inner core,” was employed for the first time in 1926 by Yu Shangyuan and later by Huang Zuolin (1962) to encapsulate the imagistic, quintessential character of traditional Chinese theatre.

Overall, what triumphed in these shows was the versatility of the xieyi principle of Peking Opera; from comic laughter to fairy-like bliss and from military planning to tragic despair and loss, xieyi can evoke and vividly depict a wide range of moods, situations and settings without any or with little recourse to material stage props.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Letizia Fusini.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.