Vessel. 26-27 October 2019. OzAsia Festival, Adelaide, Australia.

Now in its twelfth year, Adelaide’s OzAsia Festival is Australia’s only annual festival that focuses on contemporary work from Asia. Also programmed are works of performing and visual arts from anywhere in the world that reflect a deep and meaningful connection with Asian cultures. In this latter category was Vessel, perhaps the festival’s most breathtaking dance work this year, a collaboration between Belgian choreographer Damet Jalet, and Japanese sculptor Kohei Nawa.

Jalet and Nawa: A Cross-Disciplinary Collaboration

Jalet’s collaborations are frequently international, and the commissioning and development of his creative work have brought him to Japan for numerous residencies. In a pre-show interview in Adelaide, he told me the story of how Vesselcame to being. He was in Tokyo working on a new piece with choreographer Sidi Larbi Cherkaoiu at the time of the 2011 earthquake. “I was in a dance studio doing an acrobatic movement and remember landing and feeling dizzy,” he recalls. “It was not me, but it was the whole room that was shaking.”

Two years later, he was back in Japan and experienced Kohei Nawa’s “Foam” installation at the Aichi Triennale in Nagoya. Nawa’s work consisted of bubbling foam on black sand, sculpted with light, suggesting the movement of a lava flow. Jalet remembers it as “a moving landscape,” what he calls “a portrait of organicity made with inorganic material.”

Jalet, whose longstanding interest in volcanoes was reinforced by his 2011 encounter with Japan’s shifting tectonic plates, was determined to collaborate with Nawa. When he later returned to Japan with dancer Aimilios Arapoglou to start the residency that resulted in Vessel,he wished to “create something that was at the meeting point of our two disciplines.” “I wanted to blur the line and at the same time work with this duality of his work, my work, and material bodies.” These guiding principles are very much in evidence in the completed work, presented in Adelaide from 26-27 October with a company of seven dancers.

A World Comes into Being

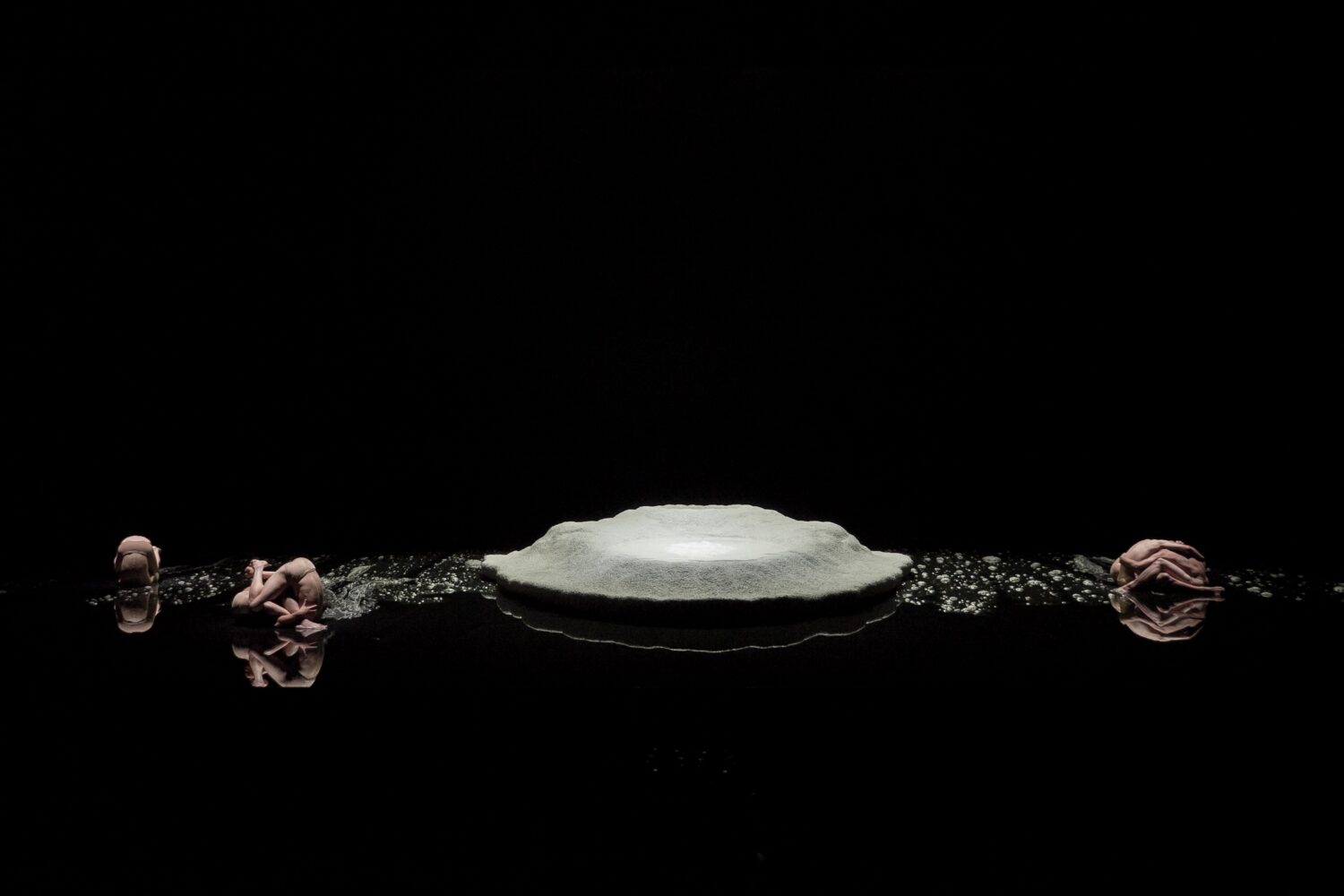

Vessel begins not with bodies in motion but in a void. A horizontal, white oblong shape slowly becomes visible in the darkness. The sonic environment suggests the interior of a womb or a submarine.

As the eyes adjust, a slender white island emerges in Vessel. Photo: Yoshikazu Inoue

As the eyes adjust, a slender white island emerges in Vessel. Photo: Yoshikazu Inoue

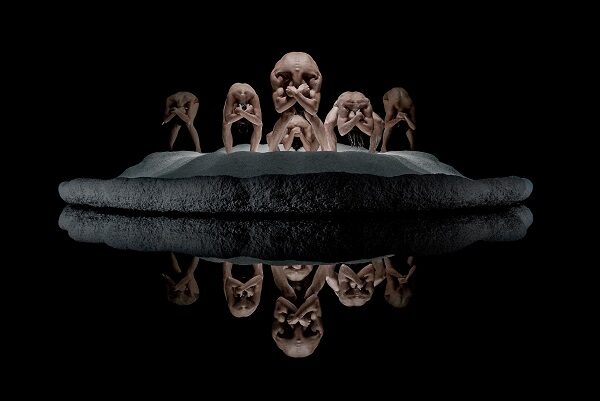

What looks like the top of a volcanic caldera comes into view, surrounded by a reflective pool of light. Two forms appear, each comprised of two human bodies entwined, clump-like. As they begin to move, they freeze in positions of balance with jumbled body parts nearly impossible to disentangle visually. They are piled up heaps of muscled flesh, with legs and arms sticking out at impossible angles, resembling a surrealist car crash.

The choreographic language of Vessel is built without identifiable human forms. For a start, dancers appear to be headless. This is a technical trick, one that requires incredible flexibility. Heads are folded down tightly into the chest, with hands touching opposing shoulders. As a result, what we see are the muscles of the back dancing, heaving, stretching, pulling, with ribcages expanding and contracting. Bodies attach to one another, pulsate and retreat, with parts of collective organisms expelled by the host.

Bodies form organic units in Vessel. Photo: Yoshikazu Inoue.

Dancers soon emerge from a kind of primordial ooze, generating non-human forms, creating eerie, writhing flesh entities. Almost as soon as parts of a body, the torso, or an arm reaches up, or when thighs struggle to pull a headless form from the water, gravity pulls it back down.

At times it feels like the audience is in a collective trance, sometimes breathing as one, sometime not breathing at all, beating to a single heartbeat. In this world, anything, including magical transformations and invisibility, seems possible.

A rich, aural landscape is created from the brilliant layering of sound by composer Marihiko Hara, building on a foundation established by Ryuichi Sakamoto. The work opens with a low sonic bass line, then the sound of crickets, a gathering of life forces. And as the sounds become contrapuntal, it’s as if we’re hearing the movement of the heavens and the earth.

A Rupture, A Fallen World

Well into the piece there is a profound fissure, a break, marked by sound. Bodies pull apart, arms fall limply, and some organisms start to individuate. One pulls away from the others and moves toward the raised white island in the middle of the stage. Suddenly, forms appear to have doubled in size and shape as they are reflected brightly in the water encircling the island.

With hands-on opposing ankles and heads tucked under, some move toward the dry land center stage, climbing up into the area around the slowly bubbling caldera. Then a sonic boom falls, an opening or perhaps a closing of the cosmos. Bodies now combine to shape an iris or flower, opening and closing like the aperture of a camera. They become insect-like, spiders in the reflected water, with human hands flapping about like flippers.

Without warming, organisms clamor up over the sides of the island. We hear a vacuum sound, suggestive of the sea being emptied of life. One of the figures moves into the white lava flow. The foam flows like lava down its back, a sculpture in motion.

Sculpture in motion in Vessel. Photo by Yoshikazu Inoue.

Without us having noticed, clouds spread out over the water encircling the island. A body rises before us in the caldera, facing out, and it feels as though we are seeing a human for the first time. Then, in less than a minute, the body sways, legs descend into a sinkhole, and it is swallowed up by clumping white foam. A final musical chord is followed by silence.

Like a volcano, this striking sculptural creation in the center of the stage is both a generator and a destroyer of life. It is a vessel of birth and destruction. In the end, only the vessel, the white caldera remains, while life has again gone silent. The human form fully revealed for only a brief moment, is gone. Ultimately, the journey of Vessel is that of all living things. We are small and inconsequential, while the natural forces that shape and contain us are unfathomably large.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by William Peterson.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.