Hong Kong Ballet gave two young choreographers a difficult task: produce the notoriously difficult Rite of Spring for the Hong Kong stage.

No performance of The Rite of Spring will ever have the same impact as its first one in May 1913, when members of the audience at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées in Paris reacted to Vaslav Nijinsky’s anti-classical choreography with shouts, hisses and – in some accounts – punches.

Still, the piece is one of the most intimidating in ballet’s repertoire. That is partly due to the difficulties posed by Igor Stravinsky’s dissonant, heavily syncopated score, but even more so to the many great versions that have been created over the last century – as Yuh Egami and Ricky Hu, choreographers of Hong Kong Ballet’s forthcoming production, are all too aware.

When Septime Webre, Hong Kong Ballet’s artistic director, threw them the idea of doing The Rite of Spring in June last year, they hesitated. Both are longstanding members of the company—Egami, now the company’s assistant ballet master, joined in 2002, while Hu, a coryphée, joined in 2008—and they have already created five works together, including versions of Ravel’s Bolero in 2015 and Carmen in 2017, but they knew that this piece would be a big step up. “We were like, ‘Are you sure?’” says Egami.

“Actually, I really wanted to say no,” says Hu. “We’re still too young.” Egami is 36; Hu is 32. “I didn’t think we could handle the music. But then we thought about it the other way around—that because we’re young, we didn’t need to think about it too much, we could just try.” After all, he points out, Nijinsky was even younger—not yet 25—when he created the piece for Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballet Russes company.

Having agreed to take on the project, Egami and Hu spent the next several months reading books, listening to CDs and watching previous productions. “There are so many versions,” says Egami, reeling off a list that ranges from Joffrey Ballet’s recreation of the original, through interpretations by Kenneth MacMillan, Shen Wei, Pina Bausch, Maurice Béjart and John Neumeier, through to Lin Hwai-min’s retelling for Taiwan’s Cloud Gate Dance Theatre and Helen Lai’s recently revived version for City Contemporary Dance Company.

To figure out their own take, Egami and Hu gave themselves some priorities. “We spent a lot of time working on the concept, starting by asking ourselves what spring means to us and how do we celebrate it in our world now,” says Egami. “We also wanted to create a Rite of Spring that our audience can connect themselves with. The original was set in a small village in Russia with a young woman who is sacrificed as a wish for a peaceful year. We wanted to make this idea accessible to an audience of today while keeping [the original’s] emotional metaphors and action.”

That led to a series of questions about what sacrifice means to people today. “We asked what we sacrifice when we build a civilization, and we came up with nature,” says Egami. That led to other questions, about whether people can coexist with nature or whether destroying it will be the inevitable outcome. “We know that we’re not doing much. Maybe as individuals, people want to do what they can. But suddenly they find themselves drinking from a plastic cup with a plastic straw. Sometimes it’s all too much. This sense of helplessness links to frustrations in everyday life.”

As February and the start of rehearsals approached, however, those frustrations spilled over to embrace their own efforts to come up with a clear central theme for their Rite of Spring.

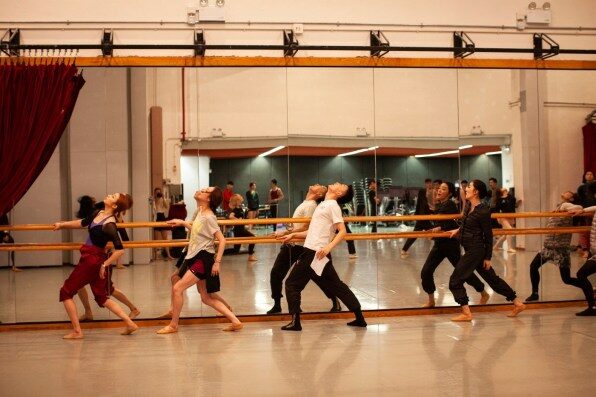

“We had so many different versions of the concept, we realized we were stuck,” says Egami. Clarity only came in the first week of rehearsals in February. “We still wanted to work with the story, but then when we started working with the dancers,” he says. “Instead of trying to guide the dancers into the storyline, we thought maybe we should let that go and focus on the chemistry that happens between the body and the music. Rather than give the dancers lots of information, we decided to give them a little and let them listen to the music.”

That turned out to be a pivotal decision. “Slowly, from the music, we got ideas,” says Hu. “It’s not about us having an idea and then finding the music to match it. With The Rite of Spring, the music is always trying to give you a message. If you really follow the music, you can get ideas. Suddenly, it was so relaxed. That was when the creation started to go really smoothly.”

Not that all the problems had been solved. Stravinsky’s music may no longer assault the ears of listeners in the way it did a century ago, but its clash of difficult rhythms and discordancies remain a big challenge for performers. Egami and Hu danced The Rite of Spring in 2011 in a Hong Kong Ballet production of Australian Natalie Weir’s version.

“So we know how complicated the music is through our bodies,” says Egami. “His music is crazy. The dancers get crazy, the choreographers get crazy,” says Hu.

“It’s not even three beats, five, six, eleven. Sometimes even no count,” adds Hu. “A lot of the accounts say that Nijinsky also didn’t know how to count the music. He was a genius dancer, but he never understood how the music worked. He could feel it, but couldn’t break it down.”

To help Nijinsky, Diaghilev had hired Marie Rambert, who was just 25 and on the first step of a career that would make her one of the great figures of 20th-century dance. Trained for three years in Swiss composer Émile Jaques-Dalcroze’s eurhythmics school of musical interpretation, her role was to steer Nijinsky through the intricacies of Stravinsky’s score.

For their musical guidance, Hu and Egami turned to Nicholas Lau, the company’s pianist, and Tim Murray, who will be conducting the Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra for their creation. Both have reassured them. Lau has helped them with the counting, while Murray has guided them through the many recordings of Stravinsky’s music. “Recent versions of the music are more organized. The music’s cleaner,” says Egami.

What isn’t cleaner, however, are the ideas of aesthetics that The Rite of Spring continues to pose, and how they can be harnessed to express ideas that are beyond the conventions of classical ballet.

“It’s a challenge for the dancers because the music of the last part, the sacrifice, is so complicated,” says Egami. “But if dancers use the equipment of how to dance with beauty on the stage, they will fail.”

“Maybe the original Rite of Spring was ugly, but it was real, about the truth,” says Hu. Like Nijinsky, their version attempts to grapple with this idea by looking for ways of expressing emotions directly. In any performance of the piece, adds Hu, “You have to be truthful. If you lie, the music will make you look very fake. If you only do the movements, not really dancing with your soul, not showing the truth, what you think, then you will look very fake.”

For the climax of their Rite of Spring, Egami and Hu have retained but reworked the original’s human sacrifice. While they are reluctant to reveal exactly what will happen—preferring to leave that surprise for their audiences—it aligns with their explorations of a world where the relationship between people and nature is becoming ever more strained.

“The second part [of our piece] is about a transfer from ugliness to truth,” says Hu. “So for us, ugly is not really ugly. Everything must be showing the real.”

This article is brought to you by

Yuh Egami and Ricky Hu’s Rite of Spring is performed at the end of this month as the finale of a triple bill marking the end of Hong Kong Ballet’s 2018-19 season. Also in the program are Wayne McGregor’s Chroma and Justin Peck’s Year of the Rabbit. Click here for more information.

This article originally appeared in Zolima CityMag on May 16, 2019, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Simon Cartledge Zolima CityMag.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.