I naively asked the production team which translation they used for the production since I assumed none of them read Greek. Their response was that, ‘[the translations] are all so different, so we used a bit of each of them.”

The magnificent orchestration by writer, director, and designer Don Fex was immediately notable. He kept the 15 talented cast members moving at a ferocious rate, constantly working at a high level of performance. Steph Goodwin’s Athenian heroine Lysistrata, set to lead the women into an angry attempt to do away with the absurdity of war. Despite the 1950’s setting, and a lot of colorful contemporary vocabulary, the show never strayed from the essential meaning of Aristophanes work, or at least the way we have come understand it. This is a feat of near brilliance on the part of the director, who has a definite talent for comedy and who obviously did some very serious work adapting the available English language translations to the theatrical space at the Gladstone Theatre.

Aristophanes’ erotic and playfully serious anti-war creation, was first produced in 411 BC, but the universal theme of this work has allowed it to easily withstand the test of time. No serious theatre company would dare call itself professional if it did not try to produce this work at least once in its lifetime. The fact it still has such an impact on artists of the stage and their audiences, was very clear last night at the Gladstone. The howls rose as the proud, self-assured bombshell style blonde, 1950’s Lysistrata came slinking in, calling her female troupe to assemble before her while batting her eyelashes and giving all the men the most powerfully mixed messages of sex, anger and defiance. The poor males went into a state of shock.

A playful little prologue staged by the director suggested the more serious turn of events about to take place, as we were introduced to Kenny Hayes’s original music and bouncy rhythms, Maureen Russell’s flurry of 1950’s crinolines and fluffy skirts, and the scenic team’s comic book styled row of pastel-colored houses with doors that didn’t open and white picket fences that kept the women well enclosed in their tight line of look-alike homes. The women march in and out, clinging obediently to their husbands illustrating how the quiet, simple life is crumbling. Representatives meet from Athens, Thebes, Sparta, Corinth, the Peloponnese regions and many more whose men have neglected them for the sake of the ridiculous 21-year-old Peloponnesian war between Athens and Sparta that rings bells with our contemporary reality. This must stop says Lysistrata, and the struggle is intended to put an end to this phallocentric relationship which has obsessed the men for too long and ignored the women’s pleas.

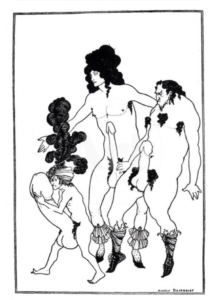

Then the dialogue begins. The women hatch a plot, and the play shows how they contrive to withdraw sexual privileges from their husbands and lovers until the men put an end to the war. The older women invade the Acropolis, the site of spiritual and financial power in the country, standing their ground despite the furious reaction of the men who want to burn the place down to remove the women. They all suffer from this decision, but it’s the men who suffer the most. They plead, grow desperate, weak and are soon transformed into overblown phallic monsters of the kind one can see in the ink drawings of Aubrey Beardsley, a contemporary of Oscar Wilde who also made those memorable, delicate and oh so cruelly hilarious illustrations of the play, bringing much to the Art Nouveau movement towards the end of the 19th century, even if the set seems to ignore all that but the esthetic mixture was very refreshing! .

The arrival of their great queen, Lysistrata, and the collective oath was taken by the women who swear, over a delicious glass of wine, to Aphrodite, goddess of love, beauty, and pleasure, never to give in to their husbands until peace is restored to their city.

The two choruses appear, the masked old men and the masked old women, who carry on the confrontation which retains the tradition of Greek tragedies to keep the story going to maintain the desperate anger of the women and the vicious defense of the men who define themselves as phallocentric warriors. The sneering city magistrate (William Beddoe) is also excellent as the hateful misogynist, swearing his disdain for women, inciting the men to ‘attack’ those wanton creatures until they abandon the struggle, even though they are terrified by these aggressive female creatures whom they don’t recognize. The famous explanation of the ball of wool, presented by the women, illustrates how men should be cleansed, trussed and tied up like a ball of wool, structured for peace just as women, so they will no longer need war. The central arguments are retained and enhanced along with references to the playwright Euripides and to the pantheon of Greek gods to punctuate the growing desperation of all involved.

As these frustrated voices let off steam and roar their anger in the right dramatic keys, the performances became angrier and angrier. Carley Richards playing the tough Spartan Lampito, with a remarkable Russian accent and a manlike dark suit is ready to get down to business. Certainly, a reference to the political splits in our own world.

Myrrhine (Emma Hickey), the sexy Lampito from Thebes, spends a whole scene promising much to her husband, Cinesias, but gives him nothing more than a hugely swollen lower part (one of Beardsley’s favourite characters!!) as she tortures him by looking for last-minute excuses to make herself even more desirable, thus overheating her nervous wreck of a husband, beautifully captured by the sweating, squealing Nicholas Maillet.

In Aristophanes’ time, actors were all men so the males were identified by sporting large, erect leather phalluses. But here since we have biological women playing female characters, the erect object takes on a different meaning. As the female actors became more and more aggressive and resistant, we see the men, in terrible physical discomfort, dragging around these huge swollen objects strapped to their groins. The phallus has become a punishment, not a glorious symbol of power, the sign of the male downfall imposed on those who refuse to accept peace.

Raucous movements, double entendres, dicey innuendos, exaggerated comic gestures; nothing is delicate about this show…it all hangs out. But that is what gives the mixed earthiness it seeks. It is a ‘female’ war and Kenney Hayes’ music contributes its soft caresses, as well as its war-like sounds, its drumbeats and its rhythms that suited the moment.

No need to describe too much. Its all in the staging, the sense of fun tinged with serious anti-war comic criticism that is clearly at the bottom of the original text. But this director has brought it all to life in a most contemporary way.

This article was originally published on Capitalcriticscircle.com and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Alvina Ruprecht.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.