Marin Sorescu’s Jonah was originally published in 1968 and is considered the playwright’s masterpiece. It’s the famous monologue of the Old Testament fisherman, who endures his dark night of the soul trapped inside a whale.

“Jonah! Jonah!” he cries out, first arriving on stage. “Actually, I myself am Jonah,” he confides to us. “I call out my name to trick the fish, because Jonah is unlucky. Mother, give birth to me again! My first life hasn’t quite worked out. It can happen to anyone.”

Thus biblical inspiration serves as a channel for commentary on the human condition, with all its tragedy and comedy. Fable-like, the play turns the prophet’s tale inside out, revealing to the audience what happened to Jonah inside the whale’s stomach by way of subtle philosophy.

“There should be a grid at the entrance of every soul, so no one can get inside it with a knife.” Jonah remarks from inside the fish’s belly.

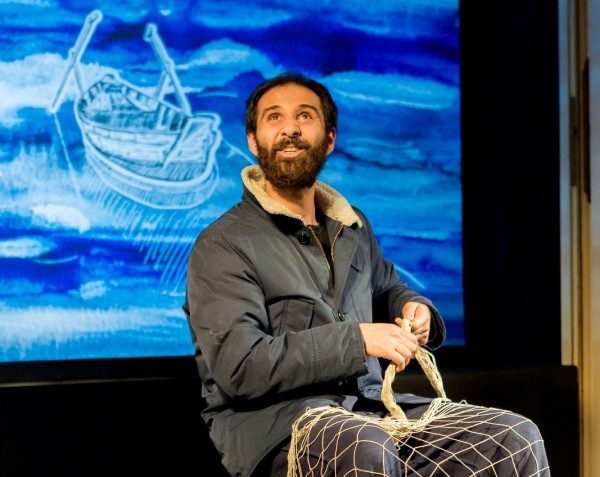

It’s worth noting Sorescu’s advice that if the second part becomes too difficult, a different actor can play it. Here, the only Jonah is Alin Balascan, an actor most compelling when comic, though there’s something sad too in his quirky and naïve persona:

“I can talk! Let’s see if I can be quiet as well. I’ll keep my mouth shut…I’m too afraid.”

Balascan is a natural actor from the beginning, but becomes truly engaging in moments of tense drama: he seems to entertain and question both himself and us, causing the audience to forget what a strain a one-man show can be. The ending is extraordinarily surprising…and chilling.

Video and light design play a major role in the production. Gargoyle-faced fish pace the screen, projected onto it throughout, Jonah interacting with them and commenting on them. A quiet video-montage introduces Balascan before he arrives onstage: a bearded man contemplating the sea. Later, as Jonah’s swallowed by the projection of a cartoon whale, we’re taken for a long time down its trippy esophagus. It’s a modern twist that really makes the story come alive and matches its linguistic dynamism. Meanwhile, the whale’s innards inspire thoughts of both a salt mine and a slow-motion techno club. Traditionalists may not like such moments–a definite departure from Sorescu’s original vision–yet they work. At times the production seems in danger of being overly bright, yet Balascan’s suppleness wins through, always serving the play and never overshadowing it.

Jonah, as performed here, is the product of great, imaginative literature matched with great theatrical effort. Balascan, who is new to the part, asked himself if it was possible to put Romanian emotion in the English language and came to the conclusion that Sorescu’s piece is “much more than something Romanian.” And indeed, Jonah is–triumphantly–about humankind.

This article originally appeared in Central and Eastern European London Review on May 21st, 2017, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Andreea Scridon.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.