The idea here is both exquisitely complex and wonderfully simple. On the one hand, Chris Goode’s show, Jubilee, is marking the 40th anniversary of Derek Jarman’s alternative cinema classic, the dystopian, ultra postmodern homage to a particular moment in British history – the year 1977– the simultaneous celebration of Queen Elizabeth II’s silver jubilee and the irrepressible, all-consuming advent of the counterculture of punk. On the other hand it is a state of the nation play.

In many ways, Goode’s Jubilee is a re-enactment of Jarman’s. The plot of the film is followed very closely with all the cinematic lounging around for atmospheric effect left often untouched and lending a slight clunkiness to the stage production. Not that this matters, given the overarching irreverence of the genre of punk itself, which frames both the film and its adaptation. Consequently then, Goode makes no attempt at a dramaturgical repurposing of the film’s content but instead makes other interesting interventions. One is updating the monologues of Amyl Nitrate – the honorary narrator of the film – or the ‘historian of the void’ as described in Goode’s cast list. In the film the character was played by Pamela Rooke a.k.a. Jordan, a model and actress, and the face of punk as fashioned by Malcolm MacLaren and Viviane Westwood. In Goode’s version, the part is played, with not negligible sass, by Travis Alabanza, the Duckie and Royal Vauxhall Tavern star – and ‘one of the most prominent emerging queer artists’ according to Dazed and MOBO – who also ad libs and works the crowd as required to notable effect.

Casting decisions therefore form one of the main ways in which Goode makes a statement in this adaptation, and for him, as many slogans on the walls of Chloe Lamford’s set testify, punk equals queer, and queer includes all forms of marginalisation – gender, race and disability.

Another of Goode’s ingenious interventions is the way in which he deploys the game of time travel set up by Jarman himself. In the film (and its adaptation) the story of the group of disillusioned and angry punks squatting in post-apocalyptic London is framed by the story of Elizabeth I travelling from the 17th to the 20th century together with her astrologer John Dee and Ariel, the spirit from Shakespeare’s Tempest (played in the film by a long term Lindsay Kemp associate David Haughton, and here by Lucy Ellinson, who also perhaps significantly plays the performance artist Viv). In Goode’s production, most notably then, Elizabeth I is played by Toya Willcox, the original creator of one of the central parts in Jubilee – the character of Mad. There is a mythical story about the way in which 20-year old Willcox worked her way into the film, making Jarman forego his own fee in other to keep the part from being cut, and forming the beginning of a beautiful friendship and a glittering acting career. In Goode’s version, the new Mad, Temi Wilkey, and Willcox join forces at the end to rouse the crowd with an old Toya hit together.

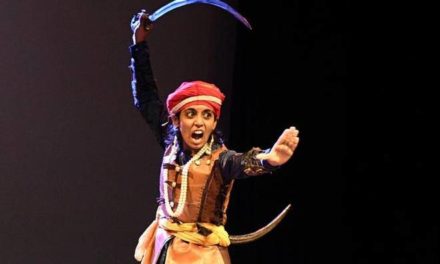

However, contrary to most expectations, punk rock is not the only music featured in this version. In fact, there is a sense that the show’s playlist spans the four decades in between the two Jubilees, and more – including an electro version of ‘Jerusalem’, Leigh Bowery/Minty’s ‘Useless Man’, Nouvelle Vague’s rendition of ‘Too Drunk to Fuck’, and not least, M.I.A’s ‘Bad Girls’ as a kind of centrepiece, with a striking ensemble dance number at the top of act two, choreographed by Sasha Milavic-Davis. Adam Ant’s Kid from the original finds his equivalent in mercurial Yandass Ndlovu and her both soulful and explosive hip hop numbers. So there is no space for any kind of nostalgia in this piece, and Goode’s second major statement transpires to be that punk is an attitude rather than a period-specific genre of music.

Reminding us that he is above all a consummate writer, Goode peppers his adaptation script with irresistible moments of wit and searing aphorisms, and as director lends his production moments of touching lyricism – as with the subtle sketching of Crabs, ‘lovelorn but sexed up, a casualty of true romance’, played with both gusto and finesse by Rose Wardlaw. Harold Finley gets to showcase his talents as John Dee, Waitress, Cop and Borgia Ginz, a legendary impresario, originally created for the film by another star of the 1970s arthouse scene, the Incredible Orlando. Eminently watchable Sophie Stone as Bod, Gareth Kieran Jones as multiple bit parts, and the tandem of Tom Ross-Williams and Craig Hamilton playing the incestuous brothers Angel and Sphinx complete the ensemble which definitely amounts to more than the sum of its parts.

The production opened in November 2017 at the Royal Exchange, Manchester. In London it finds an apt spiritual home in Sean Holmes’ Lyric Hammersmith, focused on upholding ensemble values and a European aesthetic. As a performance spectacle, however, Goode’s Jubilee falls slightly short of both the continental metaphorical grandeur and the British/Jarmanesque brash astringence.

There is potentially another bit of significance to be found in this act of time travel. By 1977, the UK had been a member of the European Union for only four years. In 1975 a referendum was held on whether to remain a member, and 67% of British population voted in favour. To all intents and purposes, in 1977 Britain was still in the liminal space in between the two entities, just as it finds itself once again right now. Derek Jarman’s Jubilee may be doing many wonderful things, but one of the things it does best, as Goode shows us, is express the perennial state of the British nation.

Lyric Hammersmith

15 February- 10 March 2018

Adapted by Chris Goode from the original screenplay by Derek Jarman and James Whaley

Director: Chris Goode

Design: Chloe Lamford

Lighting: Lee Curran

Sound and music: Timothy X Attack

Movement: Sasha Milavic Davies

Performers: Travis Alabanza, Lucy Ellinson, Harold Finley, Craig Hamilton, Gareth Kieran Jones, Yandass Ndlovu, Tom Ross-Williams, Sophie Stone, Rose Wardlaw, Temi Wilkey, Toya Willcox

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Duška Radosavljević.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.